The Great Railroad Revolution (2 page)

Read The Great Railroad Revolution Online

Authors: Christian Wolmar

America was made by the railroads. They united the country and then stimulated the economic development that enabled the country to become the world's richest nation. The railroads also transformed American society, changing it from a primarily agrarian economy to an industrial powerhouse in the space of a few decades of the nineteenth century. Quite simply, without the railroads, the United States would not have become the United States.

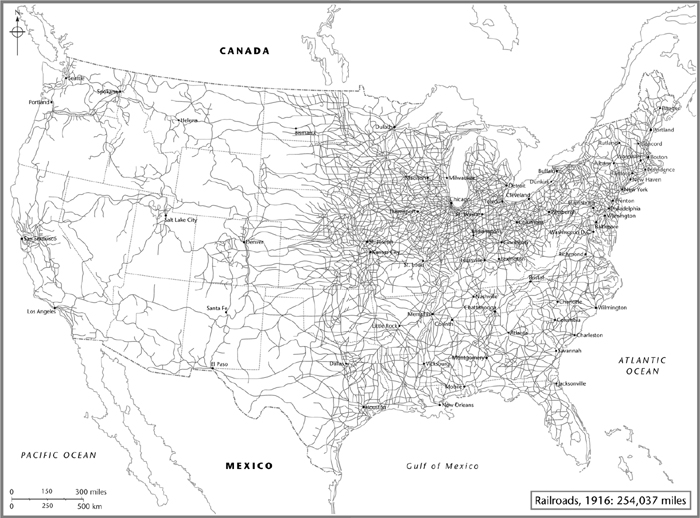

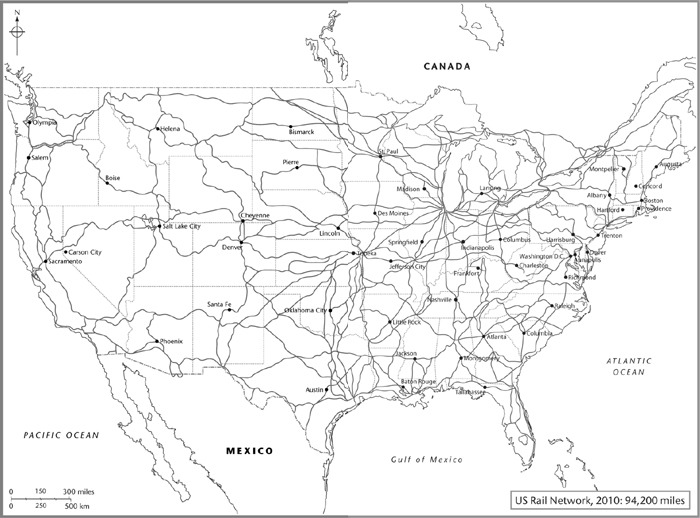

The extraordinary growth of the railroads changed the very nature of America. From modest beginnings in the 1830s, the mileage grew to cover nearly two hundred thousand miles by the turn of the century, more than in any other country in the world. Yet the epic tale of the growth of the railroads and their influence on the development of the nation is now largely forgotten and ignored. By the middle of the twentieth century, as the automobile and the airplane continued their relentless march toward domination of the US domestic transportation network, the historical importance of the railroads was being written out of the nation's consciousness. Passenger railroads were reduced to a loss-making irrelevance. Mention the American railroads to most people, and they will talk about them as a spent force. Yet railroads still flourish in the United States and are a vital part of the infrastructure. The tracks are still there, but even when the huge freight trains run through town centers, they somehow remain invisible to the American public. It is a surprising fact that America's railroad network remains the world's largest and is the bedrock of the country's freight transportation system. There are, too, signs of a revival in passenger railroads, with money available from the federal government

thanks to President Obama's welcome, if flawed, stimulus package of 2009 and a rise in passenger numbers on Amtrak services. America may have gradually disowned its railroad heritageâbut now is the time to reclaim and reinstate it. This book attempts to do just that.

Although there are countless tomes on railroad history, few have tried to tell the story of the American railroads and their impact in one concise narrative. That has meant taking a very selective approach, and inevitably many facets of the rich story of America's railroads have been left out. Inevitably, it has been impossible to be comprehensive, and I have had to be selective on what aspects to cover in detail. I have, for example, chosen particular railroads to look at in some depth as examples, since there is no way that any book of a reasonable length could adequately cover the history of 250,000 miles of track, which was America's route mileage at the railroads' height. Obviously, most of the prominent companies are mentioned in the book, but there are numerous omissions for reasons of space or repetition.

As with several of my other books, I have focused more on the nineteenth century than the twentieth. That is deliberate. It was in the nineteenth that the railroads were being built, and they reached their zenith soon after the turn of the century. The story of the twentieth is one largely of decline and waning influence, a time when railroads were losing their importance and where opportunities to make the best use of this historic legacy were missed. Although this period is covered in less detail than the earlier times, I try to explain why what started out as a love affair between the American people and their railroads has turned out so badly and why an industry that makes such a positive contribution to America's economy today is largely ignored or even reviled.

I have highlighted for particular attention the role of a few of the individuals who created or ran the railroads, but again for reasons of space I have left out many other great characters who have contributed to the making of American railroads during its near two centuries of existence. I make no apology, but hope the reader will understand how difficult this selection has been.

The first chapter looks at how railroads emerged and why they developed as opposed to other forms of technology. Each aspect of what constituted a railroad had to be conceived, developed, and refined: track beds, rails, cars, and locomotives. Railroads brought together the most complex

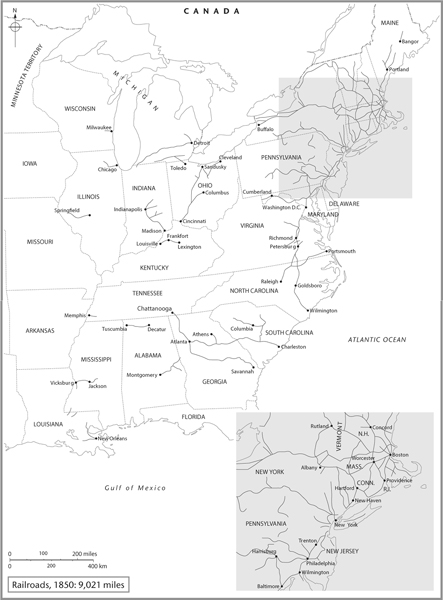

set of technologies developed since the dawn of civilization. And America was a pioneer, joining the railroad age just after the first modern railroad had been opened in the United Kingdom. America was a young country, ripe for the railroad revolution, and within a few years of the first line opening, there were already a thousand miles in short separate lines laid principally on the Eastern Seaboard. Quite clearly, the railroad's moment had arrived. It soon became obvious to its early promoters thatâon grounds of efficiency and cheapnessâlocomotives rather than horses must be used to pull the carriages and railroad trucks. The first significant railroad had been developed in Britain in 1830, and several European countries had quickly followed suit. The United States fast caught up and was soon leading the world in railroad mileage. The railroad age had arrived, and nothing could stop it.

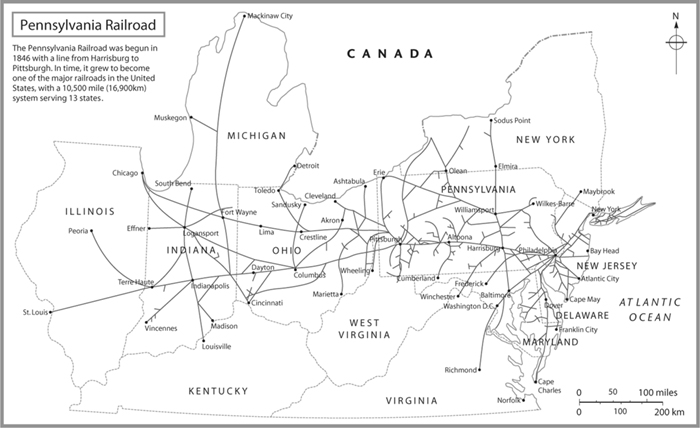

The second chapter shows how America's relationship with the railroads soon became a passionate affair. They grew symbiotically, rapidly spreading across the more economically advanced states. From harboring doubts about the railroads, suddenly everyone wanted to be connected to the railroad. The burgeoning United States adopted railroad technology faster and with more enthusiasm than any other nation, embracing the new invention that seemed to reflect the pioneering spirit of the age. Up and down the East Coast, railroad lines sprang up with amazing speed, stimulating economic growth that would change the way people lived and eventually make America the most powerful nation on earth. Of the twenty-six states that constituted the Union in 1840, only fourâArkansas, Missouri, Tennessee, and Vermontâhad not completed their first mile of track. The beginnings of what would become the major railroad companies were established during the 1840s with the opening of the New York Central & Hudson River and Pennsylvania lines. However, for the most part in the 1830s and 1840s, the development of the railroads was a local affair. People wanted to have easy access to the local town, or possibly to the other end of the state, rather than across the nation. These early railroad companies were a true ragbag of outfits, ranging from, literally, one-horse companies carrying coal out of a mine to longer lines stretching into the outback and carrying thousands of passengers a week.

The third chapter shows how the railroads took off as an industry in the years running up to the Civil War. The 1850s saw a massive increase in

the pace of track development, and the mileage more than tripled during the decade. This was a period of strong economic performance, both driven by the railroads and speeded up by their construction. Although most of the railroads were built by the private sector, little of this remarkable growth would have been possible without government support through various mechanisms, such as allowing companies to run lotteries, the granting of monopolistic rights, tax exemptions, and land grants. It was the start of a difficult relationship between government and the railroads.

The American railroads were bigger in every sense than those in Europe. They covered longer distances, used larger locomotives, and hauled longer trains. The railroads seemed to be tailor-made for the huge American landmass and for the indomitable spirit of its people. European countries were constrained by reactionary governments slow to recognize the social and economic benefits of the railroads and by old-fashioned customs that those with vested interests worked hard to protect. Americans, howeverâfree from the shackles of tradition and unencumbered by obstructive governmentâtook to the new method of transportation with far more gusto and enthusiasm than their European peers.

The Civil War, covered in

Chapter 4

, was the first true railroad war and was particularly lengthy and bloody as a result. Key battles were fought around railroad junctions, railroad sabotage became a key tactic of the war, and troops were transported huge distances in a way that would have been impossible even a decade previously. The North, industrially stronger than its rival, was lent a key advantage by its superior railroads, which, crucially, were far better managed during the war than those of the South. The Unionists quickly realized that the operation of the railroads could not be left to chance and placed them under military control early in the conflict. By contrast, the secessionists never established government rule over their railroads, with the result that they operated far less efficiently. The war would also witness remarkable examples of derring-do on the railroads: the Andrews Raid (or Great Locomotive Chase) in April 1862âin which Union volunteers commandeered a locomotive on the Western & Atlantic line, deep in Confederate territory, and created mayhem as they drove it northâhas entered American folklore but somewhat obscured the true story of the railroads in this conflict.

The fifth chapter tells the story of the construction of the first transcontinental railroad in the United States. The dream of a coast-to-coast line had first been mooted as early as 1820, but it was not until the 1850s that the idea was seriously considered; its start was delayed by the Civil War, although ironically it was the absence of the Southern politicians that allowed the legislation to be passed by Congress. It was by far the most ambitious railroad project of this period in the worldâto be surpassed thirty years later only by the Trans-Siberian, the subject of my next bookâbut its exact purpose was somewhat unclear. To reach the Pacific Ocean, three thousand miles away, was an obvious ambition for the federal government in Washington seeking to unify the new nation, but it was never going to be a commercial proposition. Thanks to lobbying by a remarkable young dreamer, Theodore Judah, who gained the political backing of Abraham Lincoln, Congress passed the act to build the line in 1862. The law also allowed for massive subsidies in the form of both cash and land grants to the two companies building the line, the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific.