The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (26 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

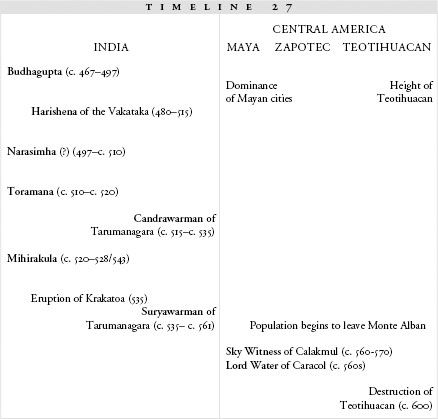

What happened to the Mayan cities is even less clear. Unlike their neighbors, the Mayan cities had remained independent of each other. Fiercely autonomous, they fought each other for power as often as they acted in alliance. A few names and deeds survive: the king Sky Witness ruled for ten years over the fifty thousand residents of Calakmul; the king of Caracol, Lord Water, defeated his neighbor, the king of Tikal, and offered him as a sacrifice around 562. Ruins testify to the ingenuity of the Mayan builders: Cancuen still stands out because of the enormous size of its royal palace; Chichen Itza had one of the most elaborate ball courts of any Mayan city, a court where players who represented life and death battled to slam a ball through a stone ring in a sacred ritual that remains obscure to us (although reliefs of decapitated players suggest that bloodshed played a large role).

But most of the Mayan records—the elaborate calendars, genealogies, and chronologies—break off at 534, and the silence lasts for nearly a century. Archaeology must fill the gap: outlying fortresses of the larger Mayan cities were burned, the population dwindled, tree rings show long, cool, wet summers. Hunger stalked the Maya as well. The dearth of official records speaks its own message. When catastrophe struck, divine sanction could not preserve the power of kings—not once their people realized that the kings were helpless in the face of famine, drought, and flood.

*

Between 510 and 529, an Arabian king converts to Judaism, while the emperor Justinian marries an actress and claims to speak for God

I

N

A

FRICA

, just east of the Nile, the armies of Axum were planning to invade Arabia.

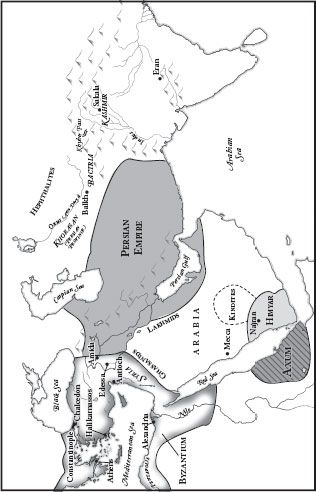

Their target, the Arabian kingdom of Himyar, lay just on the other side of the Red Sea. It had existed in southern Arabia for six hundred years, expanding slowly until it controlled not only its ancient territory on the southwest corner of Arabia but also the central Arabian tribes known as Kindites.

The peoples of Himyar and Axum were not all that different; centuries of migration across the narrow strait between Africa and Arabia had produced African-Arabian kingdoms on both sides of the water. But Axum had been Christian for two hundred years, since its king Ezana had converted and forged a friendship with Constantine, and since then Axum had also been an ally of the Romans.

1

Most of Himyar, on the other hand, still followed traditional Arab ways—a useful phrase that covers a mass of divergent and contradicting customs. In 510, to be Arab meant nothing more than living on the Arabian peninsula, and even that designation grew fuzzy up towards the north, where the peninsula shaded over into Persian-and Roman-controlled land. Cities populated the coastal areas and the north, while nomadic tribes known collectively as Bedouins roamed the desert; and even though the Bedouins and the urban-dwellers were descended more or less from the same tribal ancestors, they lived in competition for resources and in mutual disdain for each other’s lifestyle.

They were further divided by religion. A Nestorian form of Christianity had spread patchily down into some of the northern Arab cities, and even into some of the northern tribes. The Ghassanids, originally nomadic tribes from southern Arabia, had wandered northward in the previous century and settled down as farmers just south of Syria; there they converted to Christianity and in 502 had agreed to become

foederati

of Byzantium. But most Arabs were loyal to traditional deities who were honored at various shrines and about which we know almost nothing. For many years, the greatest of these shrines was found at the city of Mecca, halfway between Himyar and the Mediterranean Sea. The shrine was called the Ka’aba; it housed the Black Stone, a sacred rock (possibly a meteorite) oriented towards the east. Tribes came from the interior to pay homage at the shrine, and war was prohibited for twenty miles around.

2

28.1: Arab Tribes and Kingdoms

From his corner of the peninsula, the king of Himyar, Dhu Nuwas, could see two great threats looming in the distance. To the northeast was Persia, which had already invaded the Arab peninsula at least once; since Shapur II’s expeditions in 325, the Lakhmids (Arab tribes who lived on the southern side of the Euphrates) had served as the Persian arm into Arabia, dominating the tribes nearby with the help of Persian cash and weapons. To the northwest was Byzantium, which had ambitions to spread into Arabia with the help of

its

two allied kings, the rulers of the Axumites across the Red Sea and the Ghassanids south of Syria. Even with the Kindites as a buffer, Dhu Nuwas faced an uncertain future.

3

So he took a highly unusual step: he converted to Judaism and declared Himyar to be a Jewish kingdom.

*

Practically no one in the Middle Ages became Jewish as a way to get ahead. But Dhu Nuwas was already beating off periodic raids launched by Caleb, the Christian king of Axum. He wanted to distance himself from the Christian allies of Byzantium without completely alienating Persia, and the Persian king, Kavadh I, was kindly disposed towards Jews.

As a Jewish monarch, Dhu Nuwas could pronounce the Byzantine and Axumite Christians in his kingdom to be his enemies. He began to arrest the merchants of both nationalities and put them to death. His purge then extended to Himyarite natives whom he suspected of belonging to a fifth column; where Christianity had spread into his country, it had done so in the upper classes, the aristocrats of his society who were the most likely challengers to his power in any case. They were concentrated most heavily in Najran, an oasis city at the intersection of caravan routes from Syria and Persia. Sometime between 518 and 520, Dhu Nuwas massacred the Christians of Najran.

Rather than preserving his kingdom, the massacre destroyed it.

4

News of the purge reached the Byzantine emperor in 521. Justin had just made his nephew Justinian consul, and the two men were dealing with renewed Persian hostility. Justin’s predecessor, the emperor Anastasius, had handed over a yearly tribute to the Persian king Kavadh I, a strategy that had yielded a number of relatively peaceful years; Justin decided to cease the payments, and in retaliation Kavadh I sent an army of Lakhmid mercenaries to attack the Byzantine borders. In early 521, Justin dispatched an ambassador to the king of the Lakhmids, Mundir, to try to negotiate a peace directly with the Persian-sponsored raiders. Among the ambassador’s party was a Syrian churchman named Simeon of Beth Arsham. Afterwards, Simeon wrote to a fellow bishop describing the arrival of the news about the massacre; the Byzantine ambassador and King Mundir were negotiating in the Lakhmid army camp when a call went up from the sentries that another delegation was approaching. It was from Himyar and carried letters from King Dhu Nuwas to his Arab colleague Mundir, telling him that the Christians of Najran were dead.

According to Simeon, the letter described treachery and deceit; Dhu Nuwas had sent Jewish priests to the Christian churches in Najran bearing promises that if the Christians would surrender peacefully, he would send them all across the Red Sea to Caleb of Axum. “He swore to them,” Simeon writes, “by the Tablets of Moses, the Ark, and by the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel that no harm would befall them if they surrendered the city willingly.” But when the Christians surrendered, Dhu Nuwas ordered them slaughtered: men, women, and children were beheaded, their bodies burned in a flame-filled ditch. Dhu Nuwas concluded the letter by offering to pay King Mundir “the weight of 3,000 dinari” if he would convert to Judaism as well, forming an alliance of Arabic Jews who could unite against the Christians and drive Byzantine power entirely from the peninsula.

5

Simeon’s rhetoric is extreme, and his other writings reveal a malicious turn of mind, so his account should be taken with a tablespoon of salt. But his was apparently not the only report of the massacre. When the news reached Constantinople, Justin and Justinian threw the weight of Byzantium behind Caleb of Axum’s army, providing him with ships and soldiers and commissioning him to bring the Himyarite kingdom to an end.

Procopius records the expedition: Caleb (whom he calls by the Greek name “Hellestheaeus”) crossed the Red Sea with his fleet. Hearing of the approach, the remaining Christians in Himyar tattooed the cross on their arms so that the attacking Axumites would know them and spare their lives. Caleb met Dhu Nuwas in battle and defeated him. Later legends insisted that Dhu Nuwas, seeing his army fall before the Axumite attack, turned his horse towards the Red Sea in despair and rode into it, drowning himself and bringing an end to his kingdom—a baptism with no resurrection.

6

Caleb of Axum installed a Christian lieutenant of his own as governor, folding the territory into his own; he did not manage to keep control of the land across the Red Sea for long, but the Himyarite kingdom was no more.

But Dhu Nuwas’s letter gave birth to a rumor that still lives. The kingdom of Himyar had long ago spread across the old territory once governed by the Sabeans, whose queen had journeyed north to see the great Israelite king Solomon in his capital of Jerusalem. And Dhu Nuwas was said to have sworn his oath to the Christians on the Ark. Perhaps the Ark of the Covenant, lost long ago, had in fact been taken down into Sabea by descendents of the queen, and Dhu Nuwas’s oath meant that he

had

the Ark in his possession; and perhaps Caleb, plundering the capital city of Himyar after his victory, took the Ark back across the Red Sea into Axum.

It is still rumored to rest there, in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, in the ancient capital of the Axumites.

*

S

KIRMISHES BETWEEN

Byzantine and Persian armies continued, but for a time neither empire was willing to commit to full war. Kavadh had temporarily lost his Arab mercenaries. After the destruction of Himyar, the Kindites, freed from the dominance of their southwestern neighbors, started a fight with the Lakhmids, which preoccupied the Lakhmid king Mundir for the next few years with the defense of his own people. The emperor Justin was ill with an old army wound that caused him constant pain. And the consul Justinian was in love.

He had fallen for an actress, a profession that in the eastern Roman empire had long combined on-stage performances with the off-stage servicing of male clients willing to pay. The actress who caught Justinian’s eye was Theodora; she was barely twenty and had been forced to support herself since childhood in a world where women without the protection of fathers or brothers had little choice of jobs.

Theodora’s life is chronicled by Procopius, the Roman historian who gives such a sober and trustworthy chronology of Byzantium’s military history in his

History of the Wars

. Procopius was a man’s man; he admired strength and force, he scorned uncertainty and compromise, and he believed that a real emperor should be free of female influence. His joint biography of Justinian and Theodora,

The Secret History

, was written after Justinian married his actress, and after it became clear that Justinian—brilliant and mercurial—depended on his wife. It drips with vitriol.

Despite the acidic tone, there is little reason to think that Procopius got his basic facts wrong; Theodora’s past was well known to her contemporaries. Her father had been a bear-trainer who worked in the half-time shows given by the Greens between chariot races. He had died of illness, leaving his wife with three small girls under the age of seven. The Greens had hired another trainer, and in order to survive, the mother had forced the girls to appear before the Blues as entertainers. Entertainment led to prostitution, and by the time Theodora reached puberty she had already been in a brothel for years. Procopius chalks this up to Theodora’s insatiable appetite (he claims that she could sleep with upward of forty men per night without “satisfying her lust”), but a darker picture emerges from even his sharp-tongued account: “She was extremely clever and had a biting wit,” he writes, “she complied with the most outrageous demands without the slightest hesitation, and she was the sort of girl who if somebody walloped her or boxed her ears would make a jest of it and roar with laughter.” She had, after all, little other choice.

7

When she was still in her teens, she caught the eye of a Roman official who was heading down to North Africa to take charge of a five-city district known as the Pentapolis. She went with him to his new post, but once in North Africa he threw her out. She made her way along the coast (“finding herself without even the necessities of life,” Procopius says, “which from then on she provided in her customary fashion by making her body the tool of her lawless trade”) and ended up in the Byzantine city of Alexandria, in Egypt.

8

There, she became a heretic.

In the theological wars of the previous century, Alexandria had lost prestige. Despite the age and size of the city’s Christian community, the bishop of Alexandria had been placed below both the bishop of Rome (the pope) and the bishop of Constantinople (the patriarch) in the Christian hierarchy. Resentment over this ordering of church authority made Alexandria a welcome haven for Christians who found themselves out of step with the Chalcedonian Christianity of Constantinople and Rome. In fact, Alexandrian Christians tended to think that the Chalcedonian Creed had not gone far enough in condemning Nestorianism (the belief that Christ had two separate natures, human and divine). The priests at the Council of Chalcedon thought of themselves as monophysitic, and they had carefully rejected language that might make it sound as though Christians worshipped more than one divinity: Jesus and God are “one Person and one subsistence,” the Chalcedonian Creed said, “not as if Christ were parted or divided into two persons.”

9

But the creed also maintained that Christ had two natures—and that although those natures were without confusion, division, or separation, the “characteristic property of each nature” was preserved. The Council of Chalcedon had walked as close to the edge of monophysitism as it could without stepping over, and the Alexandrians were unhappy with this phrasing. They were unhappy because it was being imposed on them and also because they wanted no hint of two-ness in their theology. The farther east you lived, the more aware you were that the Persians believed in a pantheon of deities—and the more important it became to mark off the differences between you and your foreign neighbors by insisting that you believed in only one God. Timothy III, the bishop of Alexandria, not only defended monophysitism but welcomed into his city churchmen who had been thrown out of Rome, Constantinople, and Antioch for being insufficiently Chalcedonian. Among them was Julian of Halikarnassos, who taught that Christ was

so

divine that even his human body was incorruptible, meaning that the Incarnation was “real only in appearance.”

10