The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (25 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Between c. 500 and c. 600, the cities of Mesoamerica flourish until drought and famine strike

T

HE ASH FROM

K

RAKATOA

, blown by winds far above the earth, circled the globe for five years. On the other side of the world, summers grew cold and gray.

1

Drought struck the forests and fields of the Americas, and for thirty years crop-killing dryness alternated with the vicious flooding brought on by unnaturally frequent El Niño events.

*

While the great urban civilizations of Rome, Egypt, and the east were at their height, the peoples who lived on the land in central America were developing complex civilizations of their own. But unlike the Romans, Egyptians, and Chinese, they did not write the histories of their rulers. The archaeologist can trace the rise and fall of cities, the carving out of trade routes and the exchange of goods, but the historian has very little raw material to shape into a narrative. There are statues and carvings but no explanations; there are lists of dates and rulers but no tales of their deeds.

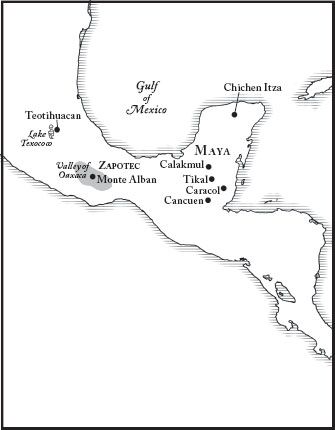

We can start to piece together at least the broad outlines of a story beginning in the sixth century. On the peninsula that jutted out from the central American land bridge into the Gulf of Mexico, a familiar phenomenon was shaping itself. A group of tribal peoples, loosely related by language and culture, building cities that tended to act in alliance, became distinct enough for us to give them a name: the Maya. Southwest of the Mayan territory, in the fertile plain known as the Valley of Oaxaca, another collection of small tribal territories was united (mostly by force) under the leadership of the strongest city among them, Monte Alban: this allows us to see them also as a single people, the Zapotec. Monte Alban became the capital city of their kingdom, a city occupied by over twenty thousand people and extending for fifteen square miles across ridges and valleys.

2

Both the Maya and the Zapotec wrote. Their records are terse and enigmatic, but the very nature of the writing gives us a glimpse (although indistinct) of a very different world than the kingdoms across the oceans. The development of writing in the east and in Egypt was driven by economics, by the need to keep track of goods and payments. For the Maya and the Zapotec, writing had an entirely different function. It helped them to keep track of time.

3

And calculating time was no simple matter. The two peoples shared a sacred calendar, one that placed great importance on birth dates and auspicious days; to us, this calendar seems almost unusably complex. It was based on multiples of twenty, not ten (a vigesimal, rather than decimal system), and its core was a series of twenty days, each with a different name. Each one of these days occurred thirteen times during the central American “year,” each time paired with a number, from 1 through 13; thus 5 Flower and 5 Deer were different days, as were 5 Flower and 12 Flower. This yielded a total of 260 days before the sequence of names and numbers began to repeat again; if Day 1 of the cycle was Flower 1, the day Flower 1 would not reoccur again until day 261. This 260-day cycle was the Sacred Round, but it did not coincide with the Earth’s rounding of the sun. So it ran side by side with a 365-day calendar, restarting itself a hundred days before the year’s end. It took 18,930 days—approximately fifty-two years—for every permutation of the two calendars to play itself out, and each one of those days had significance.

4

The skimpy written records of the Maya and the Zapotec fit each birth and death, each marriage and conquest, the accession of each ruler, into this framework. The passage of time, and the connection between each day and its sacred meaning, were at the center of each kingdom’s history. Time was the firstborn of creation; it was born “before the awakening of the world,”

5

so that every creative act, every god, and every human came into being already slotted into the intricate patterns of the calendar.

The third powerful kingdom on the land bridge worked out the passage of time in a slightly different way. This kingdom was centered around the city of Teotihuacan, which in

AD

500 was the sixth largest city in the entire world.

*

It was home to perhaps 125,000 people who spoke a range of languages; many of them had once farmed the nearby fields and had been moved by force within the city walls in a deliberate attempt by the kings of Teotihuacan to prevent any nearby villages from growing into cities that might challenge their power. The Teotihuacan empire was thus entirely centered within the city walls; like a fried egg, the meat was all in the center, and the edges were almost empty. It had the densest occupation of any central American city (a record it would hold until the fifteenth century), as well as more monuments to the power of its rulers.

6

27.1: The Cities of Mesoamerica

With its identity so encircled by its borders, the city built its observation of sacred time directly into its streets and walls. Little in the way of genealogies or calendars survives from Teotihuacan, but the city itself was a matrix in which sacred time met earthly existence. The city was oriented east to west, with the western horizon, the place of the setting sun, at the top of the compass. Its map was not shaped by rivers or the rise of land; it was shaped by sunrise and sunset, the phases of the moon, and the places of the stars. Its greatest structure, the Pyramid of the Sun, stood at its center facing west; a channel dug through the city’s center diverted water into an east-west flow. The city’s major thoroughfare, the Avenue of the Dead, ran through the city from north to south, with the Pyramid of the Moon on the northern end. At the southern end of the Avenue of the Dead lay the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, built in honor of the god who protected mankind.

7

Details of this god and his worship are known to us only from traditions that were written down hundreds of years afterwards, and it is impossible to know how many of these customs were already followed by the sixth century. He was later known as Quetzalcoatl, and his greatest deed was to restore life to humanity after all men and women had been destroyed in a battle between rival gods. Quetzalcoatl went down into the Land of the Dead, ruled by the Bone Lord Mictlantecuhtli, and retrieved the bones of a man and a woman. He then slashed his own penis, dripped blood over the bones, and restored them to life.

In the religion of Teotihuacan, death was not the end; it was the beginning. Bloodshed generated life. The people of Teotihuacan, like the Maya and the Zapotec to their east, believed in a force called

tonalli

, a sort of radiance or animating heat that brings life. In the words of religion scholar Richard Haly,

tonalli

was “the blood link that binds generation to generation” it “comes down to humans at the time of their birth, linking the newborn to the ancestors.” In return, humans offer blood back to the sky, in order to complete the cycle.

8

In the countries of the old Roman empire, the growing Christian consensus put life and death in opposition; in central America, life and death existed in reciprocity. The Bone Lord himself was the source not just of death but also of life; the Land of the Dead was not merely an underworld but also a place that existed side by side with the earth.

9

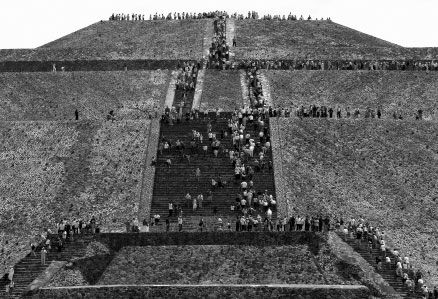

27.1: Visitors on the steps of a massive Teotihuacan pyramid.

Credit: Jonathan Kirn/the Image Bank/Getty Images

So it is not surprising that the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, where the temple to the protector god stood, was erected with blood. Its corners are mass graves filled with over two hundred sacrificial victims, buried in groups that reflect significant numbers in the calendar. The Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent stood for the beginning of time, the beginning of life. And so it was also a re-creation of the Land of the Dead, the place where and when life began.

T

HE CYCLES OF THE CALENDAR

meant that each central American king ruled in the footprints of the king who had come before him in the previous cycle. Each of the milestones of his rule—birth, marriage, coronation, conquest, death—occupied a particular slot on that elaborate calendar. But the slots were already crowded. On the day of his coronation, a king might glance at the written chronologies and see that on that very same day, in the previous cycle, a king had died or been born. Each of the 18,930 days of the cycle was the site of both past and present events.

10

In this way of thinking, the past was always present; and the rulers of central America kept their power by connecting themselves to the legendary beginnings of their world. Carvings and pictographs hint at complicated bloodletting rituals, echoing the shedding of blood that first gave life back to humanity, carried out by kings. The king who cut himself on top of a pyramid was not simply copying Quetzalcoatl’s actions in the distant past; he was with Quetzalcoatl, acting alongside of him, as his representative—and perhaps even as his incarnation.

11

Declaring yourself the friend of the god (or the god himself) was a time-honored way of keeping control of your people. It was effective, too, when the people shared the same faith—which the residents of the central American kingdoms appear, almost without exception, to have done. And as long as the gods remained powerful and popular, so did the king.

Unfortunately for the kings of the mid-sixth century, the gods they claimed as friends were also the gods of the elements. Quetzalcoatl had the wind at his side; the particular patron god of Teotihuacan, Tlaloc, was the god of rain. The deadly alternating cycle of droughts and storms that began in the 530s could mean only one of two things: either the gods were angry with them or they had simply given up caring for the city. Either way, the representative of the gods on earth was in trouble.

The results of the bad weather can be seen in the cemeteries of Teotihuacan, where skeletons begin to show malnutrition dating back to around 540. The death rate for people younger than twenty-five doubled. And then, sometime around or just after 600 (the exact date is difficult to establish), a riot broke out in Teotihuacan. Along the Avenue of the Dead, the majestic temples and royal residences were vandalized and burned. The staircases leading up to the tops of the temples, where priests and kings met the gods, were broken apart. Statues were smashed, reliefs and carvings slashed and damaged. Excavations reveal skeletons, skulls smashed and bones broken, lying in corridors and rooms of the royal palaces. The fury of the destruction was aimed directly at the rulers, aristocrats, and priests—the elite of the city who had governed it and failed to keep it safe.

12

Drought and flood affected the entire central American land bridge, but the effects on the Zapotec capital Monte Alban are not quite as easy to trace.

The torching of ceremonial buildings at Teotihuacan tells us that the people who had been moved into the city bore their rulers a fair amount of resentment; they had been living under an autocratic and heavy-handed government and were ready to revolt when famine struck. Like the kings of Teotihuacan, the Zapotecs were not mild and gentle rulers. Reliefs in the remains of ceremonial buildings at Monte Alban show conquered tribal chiefs, probably from the more distant reaches of the Valley of Oaxaca, paraded naked and mutilated by their Zapotec captors.

13

Nevertheless they had not concentrated their populations into a single urban area, something that made Teotihuacan particularly vulnerable to famine and disease when food sources faltered. Their subjects, spread out over a much wider area, were not forced by hunger and misery into a single violent revolt; and the glyphs that we

can

read do not provide us with any chronicle of decline.

But archaeology shows that between 550 and 650, the population of Monte Alban began to bleed out into the surrounding countryside. The villages and farms of the valley continued to be occupied; this was not the death of the Zapotecs, but instead a rejection of the city where its leaders lived and governed. The people survived, but the kingdom died. Like the rulers of Teotihuacan, the kings of Monte Alban had failed to convince their subjects that they were favored by the gods.

14