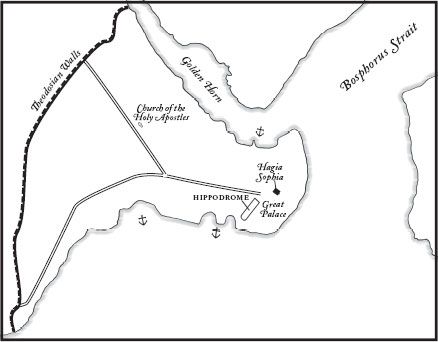

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (27 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Theodora was converted to Christianity, and for the rest of her life she held onto the extreme monophysitism that she had learned in the early days of her faith. But she did not stay in Alexandria long after her conversion. Even Procopius has to acknowledge that once she had been baptized, she gave up her livelihood and, having no way to live, went to stay with an old friend, another actress who was currently living in Antioch.

The friend, Macedonia, had discovered a new way to survive. She too had given up prostitution, in favor of joining the imperial secret police. Antioch was the third most important city in Byzantium (just behind Constantinople and Alexandria), and Justinian apparently had a network of spies and informers to keep him abreast of any unseen developments. Macedonia was one of these informers; Procopius says that she reported to her boss by writing letters, but at some point Justinian must have visited the city and asked for a personal update, because Macedonia introduced him to her friend.

Theodora was no longer in the business of supplying companionship for cash, and Justinian—twenty years her senior, smitten beyond all reason—promised to marry her. By 522 she was living in Constantinople, in a house he provided, and he was trying to talk his uncle and aunt into approving the marriage. The complication was a law passed by Constantine two hundred years earlier, meant to guard the morals of his officials: as consul, Justinian was forbidden to marry an actress. But the greater obstacle appears to have been his aunt, Justin’s wife Euphemia. Euphemia announced that she would never approve of the marriage—not because the young woman had been in a brothel, but because she was a monophysite.

Sometime around 524, Euphemia died. Almost at once, the elderly Justin agreed to pass a law revoking Constantine’s ban. “Women who have been on the stage,” he decreed, “but who have changed their mind and have abandoned a dishonorable profession…shall be entirely cleansed of all stain.” Legally redeemed by imperial fiat, retired actresses could marry anyone they pleased, and as soon as the law passed, Justinian and Theodora were married at the Church of the Holy Wisdom in Constantinople.

11

The law was Justin’s last major act as emperor. He was approaching eighty, often ill, and weary. On April 1, 527, he crowned Justinian as his co-emperor and heir. In the hot days of early August, Justin died; his nephew became emperor, and Theodora, still only in her twenties, was crowned empress.

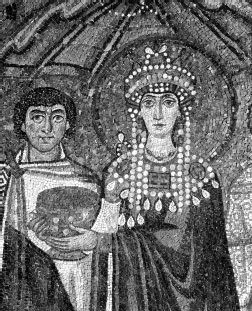

28.1: Theodora and a courtier, portrayed on a Constantinople mosaic.

Credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY

For some decades, the crown of Constantinople had been worn by military men, concerned above all else with protecting the borders of the empire from Persians and Huns, with administration and taxes, treaties and alliances. Justinian was not oblivious to these matters. But he was, above all, a Christian emperor; and he took his duties as God’s representative on earth more seriously than any emperor since Theodosius I.

12

In 528, he appointed a committee to collect and rewrite the unwieldy (and often contradictory) mass of laws passed by eastern emperors over several centuries into a single coherent code. The first volume of this code was completed by the following year, and Justinian’s own contributions to it reveal the exact place he occupied in his own ideal universe. “What is greater or holier than the imperial majesty?” he asked, rhetorically, and then decreed,

Every interpretation of laws by the emperor, whether made on petitions, in judicial tribunals, or in any other manner shall be considered valid and unquestioned. For if at the present time it is conceded only to the emperor to make laws, it should be befitting only the imperial power to interpret them…. The emperors will rightly be considered as the sole maker and interpreter of laws; nor does this contradict the founders of the ancient laws, because the imperial majesty gave them the same right.

13

“Greater or holier”: Justinian claimed for himself the double legitimacy of Roman custom and Christian authority, seeing no contradiction between the two. He was both the heir of Augustus Caesar and the representative of Christ on earth. His code regulated taxes, oaths, land ownership, and matters of belief: “Concerning the High Trinity” was the first regulation in the first book of the code. “We acknowledge,” Justinian himself wrote, “the only begotten Son of God, God of God, born of the Father, before the world and without time, coeternal with the Father, the Maker of all things.”

14

Something had happened, almost invisibly, in the eighteen months that Justinian had been on the throne: his word had become law. And not just secular law, but sacred law as well. Despite his claim to wield the ancient Roman

imperium

, Justinian’s assertion that his authority was

sacred

was a new assertion. It needed the force of Christian theology behind it, that theology which said there was one and only one right way to God, one and only one Word, one and only one Son, so one and only one man with the final authority to speak for God on earth.

The Roman pantheon could not lend such weight to imperial law; the autocratic Roman emperors of the past had used force and violence as their ultimate justification for carrying out their will. Justinian was not shy about using force, but for him, force was a means. His ultimate appeal to power was the identification between his will and the will of God. No competitors for authority were permitted: the Code of 529 forbade any adherents to the old Greek and Roman religions to teach in public. As a result, the academy at Athens, the last school where Platonic philosophy was taught, shut down. Its faculty emigrated to Persia: “All the finest flower of those who did philosophy in our time,” writes the contemporary historian Agathias, “since they did not like the prevailing [Christian] opinion and thought the Persian constitution to be far better…went away to a different and pure place with the intention of spending the rest of their lives there.”

15

Between 532 and 544, Justinian and Theodora survive a riot, Byzantine armies defeat Vandals and Ostrogoths but not Persians, and bubonic plague docks at the Golden Horn

I

N

532,

THE

P

ERSIAN AND

B

YZANTINE

emperors decided to forgo any more border spats, long enough to solve their own domestic troubles. They swore a truce with each other called the Eternal Peace. It lasted for eight years.

The emperor Kavadh had just died at the age of eighty-two, naming his favorite (and third-eldest) son Khosru as his heir. Since he wasn’t the eldest, Khosru found himself obliged to defend his right to the crown against his other brothers. He also had to put down an opportunistic revolt of the remaining Mazdakites.

*

When they rioted, Khosru massacred them, chopped off the heads of their leaders, and in an act of poetic justice, shared out all their property among the poor of Persia.

1

While Khosru was trying to establish his power in Persia, Justinian was on the edge of losing it in Constantinople. His uncle Justin had barely maintained the empire in its present state; Justinian was a reformer, a builder, an energetic hands-on emperor with his fingers in almost every imperial pie. Procopius says that he had little need of rest or food, sometimes sleeping only an hour a night and going for a day or more without bothering to eat. His vast law-code project was just the tip of the iceberg: he had plans for great building projects in Constantinople, for reconquering lost lands in the west, for burnishing the empire into a glorious kingdom of God on earth.

2

All of this took tax money, and the new taxes Justinian imposed were widely unpopular. To support his policies, Justinian appealed to the loyalty of the Blues, the faction he had supported since his youth. But the factions were inherently unstable: they were armed and ambitious and inclined to pick fights whenever possible. Factional loyalty was essentially irrational: “They care neither for things divine nor human in comparison with conquering,” Procopius wrote, “and when their fatherland is in the most pressing need and suffering unjustly, they pay no heed if only it is likely to go well with their faction.”

3

For Justinian, Blue support was a foundation of sand. In January of 532, two criminals—one of whom happened to be a Blue, the other a Green—were condemned to hanging by the courts at Constantinople. They were marched out for public execution, but the hangman proved incompetent. Twice in a row, the ropes failed to function properly and the criminals hit the ground still alive. Before the hangman could try for a lucky third, monks from a nearby monastery intervened and insisted that the criminals be given sanctuary. It was too late; the torture had already aroused the watchers. Both the Greens and the Blues rioted—not against each other, but joining forces against the government of Constantinople.

4

With a (somewhat) legitimate grievance fueling them, the factionalists went wild. City employees were indiscriminately slaughtered. Buildings all over Constantinople were set on fire; the Church of the Holy Wisdom, part of the palace complex, the marketplace, and dozens of houses of the wealthy all went up in flames. The rioters began to demand that Justinian turn over to them two city officials who were particularly unpopular, so that they could carry out their own executions. When the officials failed to appear, the fighting grew more violent. Rioters stormed through the streets shouting, “

Nika!”

—Victory!

Meanwhile, Justinian, Theodora, and the high officials of Constantinople “shut themselves up in the palace and remained quietly there.” Perhaps they hoped that the rebellion would burn itself out. Instead, the rioters went in search of a new ruler. Hypatius, the nephew of the dead emperor Anastasius, lived in Constantinople with his wife; he had gone home and barred his doors, but the rioters dragged him out of his house against his will and declared him emperor, and then escorted him to a throne they had set up in the Hippodrome (the huge chariot-racing venue in the center of the city).

5

At this, Justinian decided it would be best to make for the nearest harbor and flee in one of the royal ships docked there. Theodora stopped him. “For one who has been an emperor, it is unendurable to be a fugitive,” she told him. “If you wish to save yourself, there is no difficulty. There is the sea, here are the boats. But consider: after you have been saved you may wish that you could exchange that safety for death. For myself, I accept the ancient saying that royalty is a good burial shroud.” Theodora had spent all of her earlier years struggling for survival; she had no intention of returning to that life.

6

The speech snapped Justinian out of his panic, and the besieged emperor and his courtiers decided to hold on a little longer. Justinian’s chief general, Belisarius, and the commander of the Illyricum army, who happened to be in Constantinople on business, formed a plan. They had already summoned reinforcements from nearby cities, and those soldiers would arrive at the city shortly. With the new forces behind them, the two men would break in through opposite doors of the Hippodrome with whatever soldiers they could muster, and hope that the surprise attack would panic the crowd into stampeding. Meanwhile one of Justinian’s secretaries, posing as a traitor to the imperial cause, passed the news to the leaders of the rebellion that Justinian had fled, which reduced their wariness; another official went to the Hippodrome with a bag of cash and started to pay out bribes, producing dissention between Greens and Blues who had previously been in alliance.

7

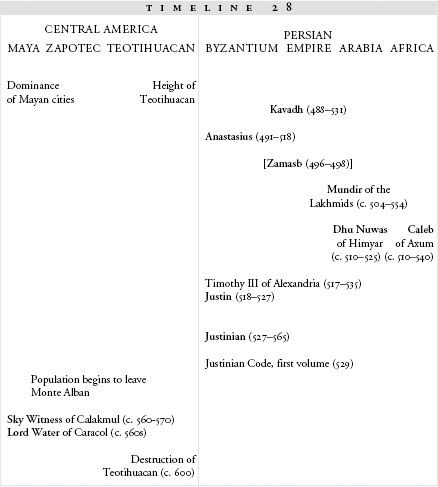

29.1: Constantinople

When the reinforcements arrived, the two generals crept through the streets, which now were largely deserted (everyone was in the Hippodrome cheering Hypatius). Belisarius assembled his men at the small door right next to the throne where Hypatius sat, while the Illyricum commander went around to the entrance known as the Gate of Death. When the soldiers barged into the crowd, the hoped-for panic erupted. Belisarius and his colleague mopped up the rebellion; Procopius says that over thirty thousand people were slaughtered in that single night. The next day, Hypatius was captured and assassinated by some unknown and useful member of the army.

The “Nika” revolt was the last challenge to Justinian’s power. For the next three decades, he would rule with an autocracy that stemmed partly from his conviction that God had put him in charge of the empire, partly from the determination to keep such a rebellion from ever threatening him again. His partiality for the Blues was markedly diminished, and the factions remained at odds with each other for the rest of his reign.

The revolt left its mark on the city; dozens of public buildings had been burned, and large swathes of the richer neighborhoods had been levelled. Justinian put into place an enormous building program, led by his master-builder Anthemius of Tralles. Enormous glittering edifices rose on the ruins. The Church of the Holy Wisdom, the Hagia Sophia, became the jewel of the restored city; Anthemius, who was also an accomplished mathematician, designed a new dome supported by arches that Procopius found almost magical.

*

“It is marvellous in its grace, but altogether terrifying,” he writes, “for it seems somehow to float in the air on no firm basis, but to be poised aloft to the peril of those inside it.” The ceiling was overlaid with gold inset with stones, which added streaks of colored light to the shining yellow surface. The inner sanctuary was lined with forty thousand pounds of silver, and the church was filled with relics and treasures: it was like “a meadow with its flowers in full bloom,” Procopius marvels, “the purple of some, the green tint of others, those on which crimson glows, those from which white flashes.”

8

While polishing up the capital city, Justinian also put into play his plans to conquer some of the lost land in the west. The kingdoms of the once-barbarians occupied the former provinces: the Visigoths in Hispania, the Vandals in North Africa, the Ostrogoths in Italy, the Franks in Gaul. But as far as Justinian was concerned, these were not kingdoms: they were overgrowths on Roman land. He intended, not to invade, but to

reclaim

. Justinian still thought of that western land as Roman, and thus as rightfully his.

He settled on North Africa as his first target and put Belisarius at the head of the campaign. Belisarius set sail from Constantinople with five thousand cavalry and ten thousand foot-soldiers. He arrived at the coast of North Africa at an opportune moment: half of the Vandal army was elsewhere, putting down an uprising. The Vandal king Gelimer (a distant relation of Geiseric, the kingdom’s founder) had too few soldiers to keep the Byzantines out. Instead he gathered up his bodyguard and fled from his palace in Carthage. Procopius was with Belisarius when the general arrived at the city: “No one hindered us from marching into the city at once,” he wrote in his account of the invasion. “For the Carthaginians opened the gates and burned lights everywhere and the city was brilliant with the illumination that whole night, and those of the Vandals who had been left behind were sitting as suppliants in the sanctuaries.”

9

29.1: The dome of the Hagia Sophia, now the Ayasofya museum in Istanbul, Turkey.

Credit: Panoramic Images/Getty Images

The Byzantines occupied the city peacefully; Gelimer, finally managing to recall his absent forces, had to attack his own city in an attempt to keep his throne, but his forces were wiped out. In that single battle, fought in mid-December of 533, the Vandals were shattered, their nation destroyed. Ever since the death of Geiseric in 477, they had been declining; Procopius says that by 533, the walls of Carthage were crumbling and dilapidated. Geiseric’s fifty-year rule had established the nation, and they had been unable to survive without him; they had never evolved an identity beyond that of “followers of Geiseric.”

10

Belisarius returned to Constantinople in triumph. In 535, Justinian dispatched him on his second western campaign: against Italy, where the symbolic heart of the empire still lay, and where the land was very imperfectly under the control of the Ostrogoth king. Enduring years of bitter quarrelling between his regents and his noblemen, the teenaged king Athalaric had been driven to seek comfort in wine. He had drunk himself to death by the time he was eighteen, and his elderly relative Theodahad had been elected to be the new Ostrogoth ruler.

11

Belisarius landed on Sicily in late 535 and conquered it without difficulty. He then moved on to the shores of Italy and captured the ancient coastal city of Naples, which had been under Ostrogothic control.

The defeat unseated the elderly Theodahad. The Ostrogoths, displeased by the city’s fall and by Theodahad’s attempts to make peace by selling part of his land to Justinian, allowed a warrior named Witigis to dethrone and kill him. The old Germanic custom of picking a warleader as king was in full force, as Witigis himself announced in a royal letter to his people:

We inform you that our kinsmen the Goths, amid a fence of circling swords, raising us in ancestral fashion upon a shield, have by Divine guidance bestowed on us the kingly dignity, thus making arms the emblem of honour to one who has earned all his renown in war. For know that not in the corner of a presence-chamber, but in wide-spreading plains I have been chosen King; and that not the dainty discourse of flatterers, but the blare of trumpets announced my elevation, that the Gothic people, roused by the sound to a kindling of their inborn valour, might once more gaze upon a Soldier King.

12

While Witigis crowned himself in Ravenna, Belisarius advanced from the coast. In December of 536, he captured Rome itself.

The easy victory in North Africa was not repeated; it took the Byzantine general another four years to advance as far as Ravenna and capture Witigis. But in 540, he took the Ostrogoth king prisoner and declared himself master of Italy.

13