The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (31 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

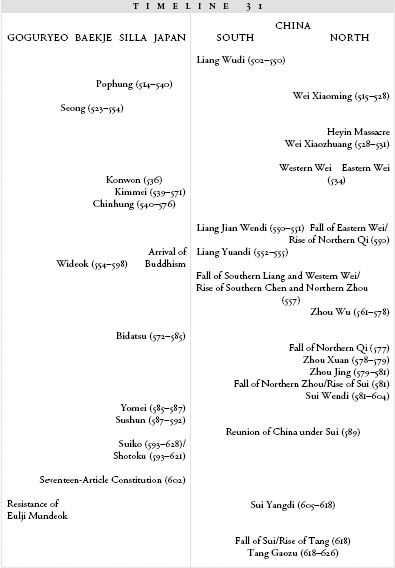

31.1: The Grand Canal

Recognizing that a country gained cohesion in the face of an outside enemy, he began a war with the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo—close enough to be considered a threat, weak enough (Silla still dominated the peninsula) to pose no serious or immediate threat to his power.

This would prove to be a disastrous mistake, one that would bring the Sui down in its infancy, but the scope of the error would not be seen for another decade.

I

N

604,

THE EMPEROR

S

UI

W

ENDI

died, ruler of a united China. He had single-handedly established China as a newly strong country: new law, new defenses, new canal, new war. Sui Wendi

was

Sui China, acting out his own virtues and vices in its landscape.

Those virtues and vices continued to work themselves out under his son, and the vices proved stronger. For one thing, no matter how great the Grand Canal—and it was indeed a dazzling network of rivers and man-dug channels that ran for over a thousand miles from north to south, with roads and post stations and royal pavilions all along its banks—it had been built with an enormous outlay in manpower. Over five million Chinese were forced to labor on the canal for part of the year, many dying of the hard labor, many more impoverished by the months spent away from their own crops and herds. Tax money had been poured into the water like sand. And, for the last years of his reign, Sui Wendi had been stymied by his war with Goguryeo. The country was proving unexpectedly hard to conquer, thanks to the stiff resistance of the great Goguryeon general Eulji Mundeok.

12

Wendi’s son Sui Yangdi inherited his crown and his problems—which he immediately worsened. Rather than retrenching, Sui Yangdi carried on his father’s attempt to build a country in less than one generation. He stepped up on the taxes and labor in order to complete the Grand Canal, and took a victory sail on the completed waterway, with sixty-five miles of royal vessels following stem-to-stern behind him—celebrating the accomplishment while ignoring the human cost. He grew obsessed with completing the conquest of Goguryeo, pouring the remaining treasury into it and sending troops into the Korean peninsula over the bodies of their fallen comrades. The war had now dragged on for nearly twenty years; the standing Sui army of three hundred thousand soldiers had been reduced to less than three thousand.

13

Sui Yangdi drafted, conscripted, and enslaved enough men for one final push. In 612, he took an army reported to be more than a million men strong into tiny Goguryeo, where Eulji Mundeok made his stand at the capital city Pyongyang. In a fierce, epically bloody battle, the Korean soldiers surrounded and obliterated the Chinese troops.

The embarrassing and horrendous defeat spelled the end for Sui Yangdi. A rebel officer declared himself to be emperor, and Sui Yangdi lost Luoyang to the revolt in 618. He died in the battle for the city, and the rebel officer ascended the throne as the emperor Gaozu, founder of a new dynasty: the Tang.

Tang Gaozu inherited a troubled country. The final years of the Sui had reduced both north and south to unhappy poverty, the king of Goguryeo was on the attack, and the treasury was empty.

14

But he also inherited a country in which, despite the fatal flaws of the Sui regime, many of the essential difficulties had been solved. He inherited a strong administrative structure, a law code, a north-south trade route, a fortified capital city, a system of governing the far-flung edges, a tax structure. The Tang would rule over China for centuries, but they owed their existence to the bloody and short-lived innovations of the Sui.

Between 543 and 620, the Chalukya kingdom spreads, a polymathic Pallava ruler fights back, and Harsha of the north almost captures the south

I

N

543,

THE JAGGED LANDSCAPE

of small kingdoms in the south of India began to smooth itself into an empire.

The king who took the first step towards conquest was Pulakesi, ruler of the Chalukya. The Chalukya tribe lived in the Deccan; they had probably come down from the north, at some distant period, but now were thoroughly native to central India. For centuries, they had existed more or less in peace, but in the sixth century Pulakesi, charismatic and ambitious, began to create a small empire out of a tribal kingdom.

Pulakesi’s capital city was Vatapi, and his conquests pushed the Chalukya empire out from that center against the neighboring tribes. He annexed the kingdom of the Vakataka, which had briefly swelled to power during the last days of the Gupta empire and now crumbled underneath his approach. He conquered land on the western coast, which meant that the Chalukya could now trade unhindered with the Arabs. But he did not rest his whole claim to authority on his sword. Instead, he boasted of having fifty-nine royal ancestors, giving his dynasty an unlikely sheen of antiquity.

1

Bolstering his authority further, he performed the horse-sacrifice: the ancient Hindu ritual that was intended to bring health and strength to the people by channelling it through the king.

The horse-sacrifice was, in the words of Indologist Hermann Oldenberg, the “highest sacral expression of royal might and splendor.” It was an elaborate and time-consuming ritual. The consecrated horse was set to wander free for a full year, under guard, before it was brought back to the king. Priests covered the horse with a golden cloth, and the king killed it with his own right hand at the culmination of a three-day festival. The queen then lay down beside the dead horse, underneath the golden cloth, and acted out sexual congress with the corpse. The strength of the horse and the strength of the king became one; the power of the horse entered the queen and she gave birth to a royal heir, who would also bear the divine strength. Power and sex were interrelated. The crown, and the passing of the crown to a blood heir, were intertwined. It was the sacrifice of an emperor, not a minor king.

2

Pulakesi’s sons built on this assertion, putting their swords behind their insistence that they had the right to rule. When the king died in 566, his son Kirtivarman took his crown and spent the next thirty years expanding the range of Chalukya power still further; inscriptions tell us that among other conquests, he defeated the nearby Mauryans, descendents of the ancient royal house that had once ruled much of India. He also built up the village of Vatapi, filling it with new temples and public buildings, beginning to turn it into a capital city.

In 597, Kirtivarman too died, and was succeeded by his young son Pulakesi II. But Pulakesi II did not at once govern his own people; for thirteen years, Kirtivarman’s brother Mangalesa served as regent, controlling the kingdom even after Pulakesi II was of age. He was reluctant to let go of the king’s sword, and as regent he carried on the conquests of his father and brother.

Chalukya momentum was rolling across the center of the subcontinent, but the kingdom’s advance would soon be complicated by another rising power: the Pallava, on the eastern coast.

In ancient times, the Pallava had lived in Vatapi, the capital city that was now at the center of the Chalukya domain. Two hundred years earlier, the Chalukya had driven them out, and they had been forced to settle in the territory known as Vengi. The long-ago defeat had produced a deep-rooted hatred between the two peoples: the Chalukya, taking the high ground, accused the Pallava of being “hostile by nature,” while the Pallava resented Chalukya expansion.

3

Around 600, the Pallava king Mahendravarman came to power. He too would prove to be a charismatic ruler who lit the fuse of a country’s expansion. For the moment, though, he avoided direct conflict with the Chalukya, instead conquering his way through the territory north of the Godavari river. Mahendravarman stands out in the sketchy chronicles of the south Indian kings, not because of his military victories (every south Indian king boasted of military victories), but because he managed to keep an interest in the arts alive, even while directing the inevitable campaigns against bordering states. He gave himself the name Vichitrachitta, which means something like “the man with new-fangled ideas” he was interested in architecture (pioneering a new method of carving out rock-temples), painting (he commissioned a scholar at his court to write an instructional manual for painters, the Dakshinachitra), town design (he built a number of new towns incorporating his own engineering techniques), music (he is credited with inventing a method of musical notation), and writing (he wrote two plays in Sanskrit, one of them a satire skewering his own government).

4

Had Mahendravarman lived in the west, with courtiers and monks who were determined to chronicle the exact place he occupied in God’s plan for the world, he would stand out in history as a polymathic king, a genius who happened to be born to the crown. Instead, we know of his accomplishments only from single lines of inscriptions.

Meanwhile the Chalukya began to suffer through civil war. The king’s ambitious uncle, Mangalesa, had refused to relinquish the throne. He was still ruling as regent but had hopes of installing his own son as king. He had led the Chalukya to victory over one of their strongest enemies, the Kalachuri; like Kirtivarman, he had added buildings and cave-temples to the capital city of Vatapi. He had every quality of a king, including royal blood—except that he was not in the direct line of succession.

In 610, young Pulakesi II rebelled against his uncle’s control. An inscription left by Pulakesi II’s court poet, Ravikirti, preserves his rationale: Pulakesi II, says the verse, claimed rule as the grandson, namesake, and rightful heir of Pulakesi I, the first of his family to rule the Chalukya as emperor. His grandfather had performed horse-sacrifice, and he alone had the right to rule.

5

Details of the rebellion are sketchy. All we know is that Pulakesi II was able to win the support of enough soldiers to assemble an army. Mangalesa’s able leadership and royal blood apparently were not enough: the tradition of direct succession trumped his strength. He was killed in the fighting, and Pulakesi II claimed the throne.

At once he picked up the sword. The list of chiefs he defeated and forced into obedience is long: Gangas, Latas, Malavas, Gurjaras, and many more. Chalukya power extended across much of the Deccan, and the Pallava and Chalukya armies began to clash. Both of their kings—Pulakesi II of the Chalukya, Mahendravarman of the Pallava—were ambitious men, bounded by sea on either side, setting the stage for an ongoing struggle that would characterize Indian history for decades.

However, a bigger threat than either of them had suddenly ballooned to the north.

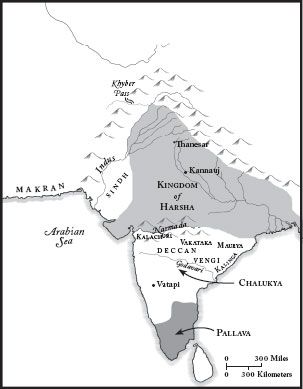

After the rule of the Guptas and Hephthalites, the northern part of India had fallen apart into competing tiny kingdoms and states. But around the beginning of the seventh century, an extraordinary boy named Harsha Vardhana inherited from his dying father the rule of the small city of Thanesar, in the north. Again, the charisma and determination of a single man would change the landscape of a country.

Unlike Mahendravarman, Harsha had a courtier who wrote. This man, Bana, left for us a eulogy praising his king’s accomplishments: the Harsha Carita. The Carita describes Harsha’s royal ancestry: “a line of kings,” Bana writes, “…dominating the world by their splendor, thronging the regions with their armies in array.” In fact, Harsha’s family was not particularly distinguished and had never ruled over much in the way of territory; but Harsha’s later conquests demanded that he be destined for glory.

6

32.1: Harsha’s Kingdom

Harsha had no sooner been crowned king than a message came to him, carried by a frantic servant. His sister Rajyasri, who had been married to a neighboring king for treaty-making purposes, had been made a widow by her husband’s sudden death. Her adopted kingdom was about to be invaded by enemies, and she herself was facing death by fire on a funeral pyre honoring her husband.

Harsha assembled an invasion force and went in to rescue her; Bana says that he lifted her from the pyramid of wood just before it could be lit. He then claimed the country for himself.

It was the first of many victories. The chiefs he defeated swore loyalty to him one after another, all across north India. As the realm grew, Harsha moved his capital city eastward to Kannauj, closer to the center of his mushrooming realm, and from there he ruled, with his sister as his co-ruler and empress. While she governed, he fought. He united Thanesar and Kannauj and defeated the neighboring tribes in an ever-widening circle around him.

7

In 620, he turned south and met the Chalukya king Pulakesi II at the Narmada river. To have any hope of holding on to his kingdom, Pulakesi II needed to keep Harsha from crossing the river. But his forces were outnumbered; the Chinese monk Xuan Zang, who spent seventeen years travelling through India during Harsha’s reign, estimated that Harsha had a hundred thousand horsemen, as many foot-soldiers, and sixty thousand elephants.

8

Pulakesi’s court poet later wrote that the smaller army prepared for battle by getting both themselves and their war elephants drunk: this made them reckless, dangerous, and overwhelming. The strategy is confirmed by Xuan Zang: “They intoxicate themselves with wine,” he writes, “and then one man with lance in hand will meet ten thousand and challenge them…. Moreover they inebriate many hundred heads of elephants, and taking them out to fight, they themselves first drink their wine, and then, rushing forward in mass, they trample everything down, so that no enemy can stand before them.”

9

Drunken courage may have played a part in the battle that followed, but Pulakesi II had the easier task: to enter Chalukya territory, Harsha’s army had to fight its way through mountain passes that were much simpler to defend than to seize. The mountains, the river, and the desert at the center of India had long militated against any king managing to sweep both north and south India into the same kingdom.

The Chalukya troops were successful, pushing back Harsha’s vast invasion force. From that point on, the Narmada was the southern border of his kingdom. This was terribly embarrassing for Harsha; Pulakesi II, great in his own sphere, was a minor ruler compared to Harsha, his kingdom a mere blot against Harsha’s vast expanse.

But he had staked out his territory and held on to it. He returned from the battle against Harsha, high with victory, and also defeated the Pallava king Mahendravarman and took away the northern provinces—Vengi, the land where the Pallava had settled after being ejected from Vatapi so many years earlier. For the second time, the Chalukya had driven the Pallava from their homeland.

10