The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (37 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Between 590 and 622, the prophet Muhammad forms a community and rules over the city where it gathers

B

ELOW THE DESERT

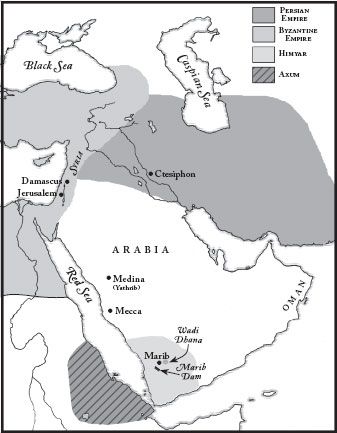

that separated them from the titanic struggles to the north, the tribes of south Arabia carried on the daily battle of surviving in a dry and hostile land. Himyar, on the southwest corner of the peninsula, was technically under Persian rule, but for most of Arabia, Persian ambitions and Byzantine crusades were irrelevant. They fought with each other, and with the elements.

In 590, a disaster far to the south shifted and broke the existing patterns of alliance and hostility.

In the center of Himyar, near the city of Marib, a man-made dam had been built back in the days of the Sabean kingdom. The dam closed off the Wadi Dhana,

*

the valley that collected rainwater and runoff from nearby mountains during wet seasons (usually only April and a thirty-day period in July and August). The dam allowed the residents of Marib to save water and channel it, through an irrigation system connected to the valley, into cultivated fields. Thanks to the Marib dam, the population of the city had been able to grow to around fifty thousand. Large cities were rare in Arabia; there was simply not enough food and water to support big and permanent gatherings of population in one place. Marib was the exception.

1

Unpredictable shifts in weather patterns during the 530s and 540s had twice caused such severe and sudden rainstorms that the dam, unable to hold the runoff, had broken. Both times, the flood caused enormous damage. “The mass of water gushed out and came down, and there was great terror,” wrote Simeon of Beth Arsham, who chronicled the history of Himyar under Persian government. “Many villages, people and cattle were flooded as well as everything which was standing in the way of the sudden mass of water. It destroyed many communities.”

2

37.1: Muhammad’s Arabia

The dam had been repaired twice. But the entire system had been badly weakened, and in 590 the dam gave way for a third time. This time, the flood was catastrophic. Villages downstream from the dam were wiped out for good; Marib, already shrunken from its former size after the previous breaches, was almost deserted. Tribes from the south who had relied on the water migrated towards the more welcoming oases along the northeast of the peninsula.

The moment of the dam’s collapse remained in their memory, and the years before the flood became mythically glorious, the height of southern Arabian civilization. The final breach of the dam was remembered as the moment when the glory ended. Just as the great flood of the ancient Near East echoed into the book of Genesis, so did the breach of the Marib dam echo into the Qur’an:

There was for Sabea, aforetime, a sign in their homeland—

two Gardens to the right and the left.

“Eat of the sustenance provided by your Lord, and be grateful to Him:

a territory fair and happy, and a Lord Oft-Forgiving!”

But they turned away from Allah,

and We

*

sent against them the Flood released from the Dams,and We converted their two garden rows into gardens producing bitter fruit….

We made them as a tale that is told,

and We dispersed them all in scattered fragments.

3

The dispersal northwards meant that Mecca, the home of the sacred Ka’aba, was no longer the only largish city where tribes gathered. Mecca did benefit from the migration; it sat on a trade route, and now it had little competition farther south. But tradition holds that many of the southern refugees ended up in the city of Medina, a sprawling settlement with fertile ground to the north. Medina was less prosperous than Mecca, but it had its own importance: it was a mixed town, made up of Jews who had migrated into Arabia long before and native Arabs, and intermarriage had tended to blunt the racial distinction between the two groups.

4

The influx of peoples northward intensified the stresses in these towns. The Arabs of Mecca, like those in other Arab towns, were first and foremost members of clans (

banu

) linked together by blood and marriage, and the clans themselves were loosely associated into larger groups, or tribes. Mecca was governed by a council made up of the patriarchs of the most powerful clans. Among these were the clans of the Banu Hashim, the Banu Taim, and the Banu Makhzum, all of them belonging to the Quraysh tribe; the Quraysh tribe was dominant in Mecca, and its clan members controlled the Mecca council.

But all was not well. Quraysh dominance was resented by other tribes. In fact, the Quraysh had been forced to fight a bloody war with the Qays tribe, just four years before the Marib dam broke, to keep their power in the city. It was called the Sacrilegious War because it was fought during a sacred month;

†

control of Mecca and its resources had been deemed more important than worship.

5

And hostility between the clans of the Quraysh itself was growing more severe. The style of government that had served the Arabs for centuries had been developed in nomadic times, when the cooperation of the clans was necessary for the survival of the tribe. In the old dry desert days, war between clans could mean extinction for everyone; they all shared the common goal of finding food, finding water, and staying alive. Now, in a Mecca growing ever more wealthy, the clans were no longer forced into cooperation. Instead they were competing for the riches of Mecca, and some clans were doing much better than others. Personal fortunes were on the rise. Widows and orphans, deprived of their family support, were pushed aside.

6

A strong king might have solved some of the knotty problems caused by this government of equals, but the Arabs were constitutionally anti-king; they had spent too many centuries relying on each other to put all of their trust in any single man.

7

The clan of Banu Hashim was one of the poorer and more resentful clans, and it was into the Banu Hashim that the child Muhammad was born.

*

His father died six months before his birth; when he was six years old, his mother too died, leaving him a full orphan. His grandfather died two years later, and Muhammad was raised by his uncle Abu Talib, an ambitious man who had fought for the Quraysh in the Sacrilegious War, and who did not rate his nephew’s comfort among his personal priorities. Muhammad grew up on the edge of survival, earning his keep by accompanying his uncle’s merchant caravans on their journeys to other cities.

8

At twenty-five, he agreed to a profit-sharing venture: leading a caravan for another Quraysh merchant, a widow named Khadija who could not take on the task herself. The first caravan he supervised went all the way to Syria, and Muhammad’s management was so expert that he doubled the widow’s investment. According to Muhammad’s eighth-century biographer Ishaq, when he came back to Mecca with the money, Khadija saw an opportunity: she proposed marriage, and he accepted. Khadija was forty years old, fifteen years Muhammad’s senior, but she would bear him three children, and Muhammad (somewhat against custom) did not take any other wives during her lifetime.

†

The wealth from Khadija’s caravans put Muhammad and his new family in the upper crust of Meccan society, but he seems to have been continually disturbed by the growing distance between rich and poor in his city, and the rampant materialism of his tribesmen. Ten years after his marriage, he took part in the rebuilding of the wall around the sacred Ka’aba—necessary, because “men had stolen part of the treasure.” Even the shrine was not exempt from greed.

9

Muhammad, devout by nature, took it upon himself to spend one sacred month of each year providing for the poor: his biographer Ishaq tells us that he would pray, give food to all the poverty-stricken residents of Mecca who came to him, and then walk around the Ka’aba seven times. In 610, while observing his month of service, Muhammad was given a vision of the angel Gabriel. His own account of it was preserved in oral tradition and passed down to Ishaq, who set it down exactly as he heard it.

He came to me while I was asleep, with a coverlet of brocade whereon there was some writing, and said, “Read!” I said, “What shall I read?” He pressed me with it so tightly that I thought it was death; then he let me go and said, “Read!” I said, “What shall I read?” He pressed me with it again so that I thought it was death; then he let me go and said, “Read!” I said, “What shall I read?” He pressed me with it the third time so that I thought it was death and said “Read!” I said, “What then shall I read?” and this I said only to deliver myself from him lest he should do the same to me again…. So I read it, and he departed from me. And I awoke from my sleep, and it was as though these words were written on my heart.

10

The next day, he again saw the angel and received the rest of the vision: he was the prophet of God, appointed to take the messages of the angel to the rest of his people.

It is no mistake that the account does not say exactly what the words are. For the rest of his life, Muhammad would struggle to receive, and interpret, and then to pass on the revelations of God. In 610, when his first vision took place, he was given only the seeds of the religion that he would ultimately found, and those seeds were simple: he was to worship the one God, the creator Allah (a deity already known to Arabs), and he was to pursue personal purity, piety, and morality, all of which were already prescribed by Arab sacred practice. The word that he would use for righteous behavior,

al-mar’ruf

, means “that which is known.” The problem with Meccan society was not a lack of revelation. It was a lack of

goodness

: the unwillingness to follow what the tribesmen must already have known (as Muhammad did) to be right.

11

For three years after the vision, Muhammad told only his family and immediate friends of his call. His first followers were his wife, Khadija; a servant named Zaid, taken captive in a tribal battle, who had married and stayed with the clan and fathered four daughters, all of whom also became followers; his cousin Ali, son of the uncle who had raised him; and his close friend Abu Bakr. Not until 613 did he begin to preach his message to the rest of Mecca. By this point, it had taken a more distinct shape. After an agonizing silence during which he doubted the reality of his vision, the revelations had returned, and the most basic divine truths had become clear.

The Guardian-Lord has not forsaken you, nor is He displeased.

The hereafter will be better for you than the present….

Did He not find you an orphan and give you shelter?

And he found you wandering and He gave you guidance.

And He found you in need and made you independent.

Therefore, treat not the orphan with harshness,

Nor turn back the beggar unheard:

But the Bounty of the Lord: rehearse and proclaim!

12

The core of the message was simple: worship Allah, care for the orphan, give to the poor, and share the wealth that had been divinely granted. At the root of Muhammad’s teachings lay always the memory of the orphan he had been.

When he began to proclaim this in public, Muhammad collected more and more followers—primarily the weak, the poor, and the disinherited. The message did not go over as well with the newly prosperous upper classes of Mecca. The clan leaders of the Quraysh complained that Muhammad was insulting them and mocking their way of life: “Either you must stop him,” they warned his uncle Abu Talib, “or you must let us get at him, for you yourself are in the same position as we are in opposition to him and we will rid you of him.”

13

To his credit, Abu Talib refused to turn against his own family, even to protect his wealth. The other clan leaders, seeing the spectre of a revolt of the underclass behind the charismatic and popular Muhammad, began a campaign of terror against any clan member who accepted Muhammad’s message. His followers were attacked in the alleyways of Mecca, imprisoned on false charges, refused food and drink, pushed outside the city walls. Some of the new converts, afraid for their lives, fled across the Red Sea into the Christian kingdom of Axum, where they were welcomed by the Axumite king Armah as worshippers of one God. Others went farther north to Medina. The members of Muhammad’s clan (the Banu Hashim) who remained in Mecca were forced into a ghetto, and a ban was declared on them: no one could trade with them, which cut off their food and water.