The Illusion of Conscious Will (49 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

In this research, six participants selected for their high hypnotizability were placed in a deep trance and were then given very emphatic suggestions to carry out the acts: Reach out a hand to a dangerous snake, and throw a flask of acid in the experimenter’s face. Just as in the earlier studies by Rowland and Young, five of the six did as they were told, reaching for the reptile and throwing the acid at the experimenter. In another condition of the experiment, however, six people who were low in hypnotizability were asked to

simulate

being hypnotized. They were simply asked to try to fool the experimenter into thinking that they also were in trances. When these people were pretending to be hypnotized, and were given emphatic instructions to do the dangerous acts, all six reached for the reptile and threw the acid! Apparently, hypnosis had no special impact on the effectiveness of the experimenter’s demands that people perform these nasty acts.

To top it off, an additional group of people who were not hypnotized and were not even simulating hypnosis were given the dangerous instructions-again, forcefully, as in the other conditions of the study. Of these, three of six reached for the snake and five of six threw the acid at the experimenter. Apparently, a deep trance was not necessary to get people to create mayhem. All that was needed was a very pushy experimenter. Participants afterwards had all sorts of justifications, of course. They claimed that they knew at some level that the whole thing was an experiment and that no one in such a setting would actually force them to do something so horrible. The experimenter, they said, was the responsible party and wouldn’t make them do something without its being safe. Still, there was no guarantee of this in the study, and these people mostly just stepped right up and did bad things.

This demonstration is reminiscent of a number of studies in which people have been led to do their worst without any hypnosis at all. The well-known obedience experiments by Stanley Milgram (1974), for instance, showed that people can be influenced in the course of a laboratory study to perform an action that most observers judge to be so harmful it would only be done by a psychopath. Still, some 60 percent of people in Milgram’s basic studies followed the instructions of an experimenter apparently to administer strong electric shocks to a person in an adjoining room up to and beyond the point at which the person exclaimed, “My heart, my heart!” and stopped responding. The fact is, people can be influenced to do harm to others and to themselves without the benefit of any hypnosis at all. The sequential agreement process that works in hypnosis works just as well in everyday life; we often find ourselves entangled in situations from which one of the few escapes involves doing something evil (Baumeister 1997). And we may do it, hypnotized or not.

One of the reasons hypnosis seems so influential may be that it releases the hypnotist to demand exaggerated levels of influence. Perhaps the occasion of performing hypnosis makes a person more brazen and persistent, more likely to ask someone to do odd or unexpected things, and judge that influence has taken place. In the normal give-and-take of polite social exchange, people may not be inclined to give each other major body blocks or loopy requests. They don’t ask others to “watch as your arm rises up,” “forget everything I’ve told you,” or “hop around like a bunny.” But in the hypnotic encounter, there is license to ask for much, and so, much is given. The social interaction that we call hypnotism may have evolved into a special situation in which it is okay to ask people to do weird things and then to notice that they’ve done exactly what was asked.

The hypnotist’s control over a subject does not seem to surpass the control available in everyday social influence. This is basically true because everyday social influence is itself so astonishingly potent. One study in which suggestions were given to fall forward, for instance, produced the conclusion that “suggestion was not at all necessary in order to procure the desired effects; a simple order (“Imagine that you are falling for-ward”) had precisely the same effect” (Eysenck and Furneaux 1945, 500).

When we focus on standard human actions, it seems that hypnosis may be normal social interaction masquerading under another name (Barber 1969). We must look beyond everyday behaviors, and even beyond the extremes of human social influence, to find special effects of hypnosis. But there do seem to be some special effects here—in the realm of unique abilities possessed by those who are hypnotized.

Hypnotic Control Abilities

It has long been suspected that hypnotized people might have super-human abilities. Fictional (or just gullible) accounts give us hypnotized individuals who can foretell the future, walk through fire, levitate, or regress in age until they reach past lives.

5

These special abilities are not substantiated by research. Studies do identify, however, a few special things that hypnotized people are able to do that appear to exceed standard human abilities:

Pain Control

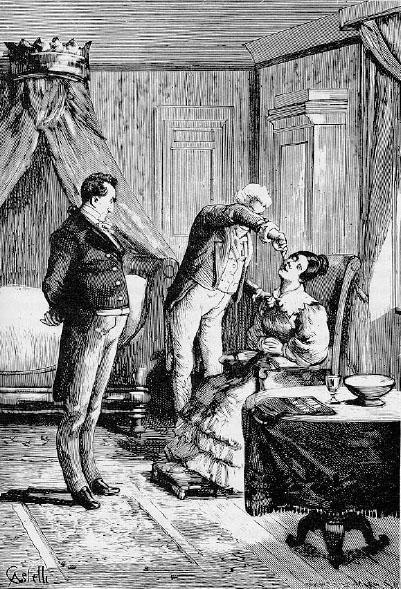

Hypnosis provides some people with an unusual ability to reduce their experience of pain. For example, in a study of pain induced in the laboratory (ischemic pain, produced by a tourniquet reducing blood flow to the forearm, and cold-pressor pain, produced by immersion of the hand in ice water), hypnosis was found to be more effective in reducing reported pain than morphine, diazepam (Valium), aspirin, acupuncture, or placebos (Stern et al. 1977). Reviews of a large number of studies on hypnotic pain control in laboratory and clinical settings indicate that this is indeed a remarkably useful technique (Hilgard and Hilgard 1983; Kihlstrom 1985; 1994; Wadden and Anderton 1982). Hypnosis with highly hypnotizable patients has been found to control pain even in lengthy surgeries and dental procedures, in some cases more effectively and safely than any form of anesthesia (

fig. 8.5

).

Mental Control

Hypnosis can yield higher levels of mental control than are attainable otherwise. For example, Bowers and Woody (1996) found that highly hypnotizable subjects who were administered suggestions to stop thinking about their favorite kind of automobile were in fact able to do so. They reported by means of button presses that the thought occurred less than once in two minutes, and some 50 percent of these subjects couldn’t even remember what car it was. Nonhypnotizable subjects who are not hypnotized, in contrast, reported experiencing the unwanted thought over three times per minute. This latter group exhibited the usual poor mental control ability shown by normal individuals asked to suppress thoughts in the laboratory (Wegner 1989; 1992; 1994; Wenzlaff andWegner2000).In another mental control study, Ruehle and Zamansky (1997) gave hypnotized and simulating subjects the suggestion to forget the number 11 and replace it with 12 while they did addition problems. Hypnotized subjects were faster than simulators at doing the math with this transposition. Miller and Bowers (1993) found a related effect in hypnotic pain control. Although waking attempts at the control of pain interfered with subjects’ abilities to perform a demanding, secondary task, hypnotic pain control did not show such interference, suggesting that it reduced pain without effortful mental control.

5.

A Web site by Terry O’Brien (2001) collects accounts of hypnosis from the media, and pokes fun at the more fantastic imaginings.

Figure 8.5

Dr. Oudet performs a tooth extraction with the assistance of Hamad the magnetizer in 1836. From Figuier’s

Mystères de la Science

(1892).

Retrieval Control

Hypnosis enhances the individual’s ability to control memory retrieval, particularly in the direction of

reduced

retrieval. Studies of hypnotically induced amnesia suggest that people can forget material through hypnosis; they either fail to retrieve items or develop disorganized ways of thinking about the items that undermine their retrieval attempts (Kihlstrom and Evans 1979; Kihlstrom and Wilson 1984). Hypnosis seems to be a good way to forget. The remarkable thing is that people can recover these memories through hypnosis as well. Items that are apparently lost to retrieval at one point may be regained through hypnotic intervention. However, research does

not

find that people can remember through hypnosis items that were not originally lost through hypnosis. Instead, hypnotized individuals do try to report memories in line with the hypnotist’s preferences. This inclination has often been mistaken for accuracy of memory report, but it is simply another indication of the malleability of the hypnotized subject’s behavior at the hands of the hypnotist. In one study, for example, twenty-seven highly hypnotizable subjects were given suggestions during hypnosis that they had been awakened by some loud noises in the night a week before. After hypnosis, thirteen of them said that this event had indeed occurred (Laurence and Perry 1983). Scores of studies show that hypnosis does not enhance the accuracy of memory and instead merely increases the subject’s confidence in false memory reports (Kihlstrom 1985; McConkey, Barnier, and Sheehan 1998; Pettinati 1988).

Wart Control

Yes, wart control. There are a number of studies indicating that people who have undergone hypnosis for wart removal have achieved noteworthy improvement. Noll (1994), for instance, treated seven patients who had not benefited from prior conventional therapies (e.g., cryotherapy, laser surgery). They suffered from warts that would respond to treatment and then return later at the same or another site. Hypnosis was presented to them as a method for learning to control the body’s immune system, and they were given both hypnotherapy sessions and encouragement to practice visualization of healing on their own. In from two to nine sessions of treatment, six of seven patients were completely cured of all their warts and the seventh had 50 percent improvement. This sounds quite miraculous until you start to wonder: Compared to what? Would these people have improved without hypnosis or with some other kind of psychological or placebo intervention? Perhaps these were spontaneous remissions. However, studies comparing hypnosis to untreated control groups have found hypnosis successful as well (Surman et al. 1973; Spanos, Stenstrom, and Johnston 1988), so there’s definitely something to this. Warts do also appear to respond to placebo treatments, though, suggesting that the effect of hypnosis may be part of a more general kind of psychological control over this problem.

Experience Control

Hypnotized individuals show a remarkable reduction in the tendency to report the experience of conscious will. This change in experience appears to be genuine and not feigned, as it even surfaces in reports given with lie detectors. Kinnunen, Zamansky, and Block (1994) questioned hypnotized and simulating people about their experiences of several hypnotic symptoms (e.g., during hand levitation, “When your hand was moving up did it really feel light?”) and also about innocuous things (“Can you hear me okay?”). Their elevated skin conductance responses (a measure of anxiousness) suggested that the simulators were lying on the hypnotic symptoms as compared to the innocuous items but that the hypnotized subjects were not.

There are many claims for hypnotic abilities beyond these. Such claims often need to be viewed with skepticism. The idea that people in hypnosis can be age-regressed back to childlike modes of mental functioning, for example, is supported by a few case examples but little research. In one case, for instance, a Japanese-American student who had spoken Japanese as a child but who denied knowledge of the language in adulthood was age-regressed in hypnosis (Fromm 1970). She broke into fluent but childish Japanese. More generally, though, when people in hypnosis are asked to “go back in time,” they appear to act in a manner characteristic of their own conception of children at an earlier age, not in a way consistent with actual earlier psychological functioning (Kihlstrom and Barnhardt 1993; Kihlstrom and Eich 1994; Nash 1987).

The five noteworthy hypnotic control abilities just discussed are ones that have been distilled from a large volume of research. Questions of unusual human abilities are, of course, matters of great scientific interest and considerable contention. Other claimed abilities that might be added to this list have been left out because insufficient evidence exists at present on which to base firm conclusions. Still, we have here a small but remarkable set of ways in which people who are under the control of others in hypnosis in fact exhibit greater control of themselves. Despite the absence of the feeling of will in hypnosis, there is in these several instances an advantage in the exercise of control. Curiously, the experience of will in this case fails entirely to track the force of will.

The Explanation of Hypnosis

The malleability of the hypnotized person is the central impediment to the development of theories of hypnosis. Imagine, for example, trying to make up a theory of “The Thing That Changes into What You Think It Is.” For no particular reason you start thinking to yourself, “Gee, maybe it has wheels,” and it turns out to have wheels. You think, “Perhaps it is large and green and soft,” and a big green blob shows up in the yard. The wheels are still there, of course, but only as long as you think they are. You wonder if this Thing could be alive, and soon it starts throbbing and opens a big eye that is now staring at you. Be careful not to think it is coming this way. This kind of Thing is not just scary, it is the worst possible topic of scientific study. In fact, this is a step beyond even the shape-shifter aliens that the heroes of science fiction so often encounter. Something that can take on different identities or shapes for its own purposes at least can be fooled occasionally into taking on a shape that gives it away. The Thing we’re talking about here will forever be camouflaged by our own guesses about what it is.