The Illusion of Conscious Will (50 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

Nightmare Science

Theories of hypnosis are faced with exactly this bewildering problem. If any theory says that hypnotized people ought to behave in a particular way under certain conditions, the hypnotist who wants to test that theory can usually get hypnotized people to do exactly what the theory predicts. After all, the hallmark of hypnosis is the pliability of the subject. If the hypnotist is interested in finding out whether the subject enters a deep, sleepy trance, subjects are normally ready to say that this is what they are experiencing. If the hypnotist is interested in determining whether the subject is really quite conscious and is merely being deceptive during hypnosis, it is not hard to get evidence of this as well. Hypnosis, it turns out, is the Thing.

The history of the science of hypnosis is brimming with stories of what happens when one scientist’s Thing meets another scientist’s Thing (please try not to form a mental image of this). Consider, for example, an interesting idea introduced by Ernest Hilgard—the notion of the hidden observer. Hilgard investigated the possibility that the psyche of the hypnotized person might have two levels, one that seems hypnotized and another that is not. In studies of laboratory-induced pain (cold-pressor tasks in which subjects immersed hands in ice water), it was found that highly hypnotizable subjects in trance, to whom analgesia was suggested, were likely to report far less pain than comparison subjects (Hilgard, Morgan, and Macdonald 1975). However, these subjects could often be induced to report higher levels of pain by asking them about their feelings in a different way. The subject would be asked, for instance, if “a hidden part of you” is experiencing something other than what was just reported. Often, subjects concurred, and in many cases this “hidden observer” could then be coaxed into talking and commenting on what was happening. In pain studies, the hidden observer often reported experiencing much more pain than the subject did, suggesting to Hilgard that there might be a dissociated part of the individual’s mind that continued to be conscious of pain even during hypnotic analgesia. The hidden observer seemed to be a pocket of conscious normality somewhere inside the hypnotized subject (Hilgard, 1986).

The spotlight on this discovery in hypnosis research was dimmed, however, by the counterdiscovery of Spanos and Hewitt (1980). These researchers thought the hidden observer might be a fabrication, just like other wild things highly hypnotized people do when asked. To test this, Spanos and Hewitt hypnotized highly hypnotizable subjects and suggested that they would feel no pain during a cold-pressor task. The subjects were asked to indicate how their “hidden part” rated cold-pressor pain using Hilgard’s usual instructions, and—so far, so good—the hidden observer complained of more pain than did the hypnotized subjects. However, some subjects in the study were given a reversed version of the hidden observer instruction, in which they were led to believe that some hidden part of them might be feeling

even less

pain than they reported during hypnosis. And indeed, these subjects concocted hidden observers whose reports of the ice water pain were lower than those of the subjects themselves. In the words of the researchers, “‘Hidden observer’ reports are engendered, shaped, and maintained by the very procedures used for their investigation” (Spanos and Hewitt 1980, 1210). Apparently, people may be packed full of an unlimited supply of hidden observers, one for each “hidden part” of them that follows the expectations of a different hypnosis theorist.

Needless to say, there continues to be controversy over the status of the hidden observer, with a lot of rhetoric and evidence accumulating on each side and no clear consensus about what is going on. This controversy is entirely typical of the scientific study of hypnosis. Discoveries and counterdiscoveries abound in this field, making it impossible on reading the research literature not to get the feeling that every researcher in this area is studying something different. Some even insist that hypnosis is nothing at all (e.g., Coe 1992). Scientists studying hypnosis seem more eager to undermine each other’s ideas than to establish an explanation for hypnosis. It is easy to develop the unflattering suspicion that researchers of hypnosis may be domineering and argumentative by nature. People who have gravitated to the study of hypnosis may be self-selected for an unusually strong desire to exert social influence, so perhaps all the squabbling arises because they can’t all hypnotize each other and get their own way. This seems unlikely, however, now that I’ve started studying hypnosis myself.

The hypothesis we must come back to is that hypnosis is the Thing. The intransigence of this topic is due to the extraordinary flexibility of the hypnotized subject. The topic is slippery by its very nature. Although it is possible to get a general sense of how much influence hypnosis exerts, and to develop a smattering of fairly trustworthy conclusions about the abilities that it creates, the deep understanding of hypnosis is still a distant goal because of the chimeric properties of the topic of study. Hypnosis becomes what people think it is.

An Assortment of Theories

What, then, have people thought it is? We know Mesmer thought it was “animal magnetism,” a colorful idea that inspires nice images of people being stuck to cattle but which has little else to recommend it. The more modern theories can be divided neatly into much the same two camps we observed in the study of spirit possession, the trance theories and the faking theories. Trance theorists have taken the hypnotized person’s word for it and assumed that there is a unique state of mind in the hypnotic trance which may indicate a particular brain state and which causes hypnotic phenomena. Faking theorists have taken a more skeptical view, in which the hypnotic subject is appreciated as someone who is placed in a social situation with strong constraints on behavior and who behaves in accord with those constraints and perhaps feigns inner states in accord with them as well. Not all these theorists would agree with this crude partition, so we should review the specific theories in a bit more detail.

Hypnosis has always been considered a trancelike state of mind. It was initially named by Braid for its resemblance to sleep (Gauld 1992). The trance theories can be said really to have gotten off the ground with the

dissociation theory

of Janet (1889). This theory holds that the mind allows divided consciousness in that separate components of mind may regulate mental functioning without intercommunication. Perceptions of involuntariness in hypnosis are thus the result of dissociation between the mental subsystems that cause action and those that allow consciousness. Ideas and their associated actions can be dissociated or split off from normal consciousness such that they no longer allow consciousness of will. This notion was elaborated by Sidis (1906), who believed that hypnosis could be explained by the specific bifurcation of the individual psyche into two selves. He thought that in addition to the normal waking self, each of us has a subconscious self, “a presence within us of a secondary, reflex, subwaking consciousness—the highway of suggestion” (179). Whereas the waking self is responsible for actions that occur with conscious will, the subconscious self produces those actions that occur through suggestion. Sidis believed the subconscious self to be a homunculus of the first order, with its own memory, intelligence, and personality.

A more contemporary version of this is the

neodissociation theory

of Hilgard (1986). Like Janet and Sidis, Hilgard proposed that dissociated subsystems of mind in hypnosis underlie subjects’ reduced control over muscular movements, in comparison to the conscious, voluntary processes that cause waking actions. Actual control is thus reduced in hypnosis along with the experience of will. According to this viewpoint, the feeling of conscious will is associated specifically with an executive or controlling module of mind. Actions that occur without this feeling are processed through some other mental module and simply do not contact that part of the mind that feels it does things. The

dissociated control

theory of Woody and Bowers (1994) goes on to suggest that hypnotic action and thought might require less cognitive effort because of this dissociation.

Neodissociation theory is also related to the

ideomotor theory

of hypnosis elaborated by Arnold (1946; see also Hull 1933). Arnold proposed that the processes involved in ideomotor action produce automatisms, and that the production of such automatisms is the fundamental phenomenon of hypnosis. The hypnotized person’s tendency to report involuntary action arises, in this view, because the action is indeed produced directly by the thought, not through any process of intention or will (

fig. 8.6

). She suggested that “in all these cases the supposedly ‘central’ process of thinking or imagining seems to initiate directly certain peripheral changes. Probably because of this direct connection, movements are experienced as different from ordinary ‘willed’ movements” (Arnold 1946, 115). Like the family of dissociation theories, this perspective suggests that behavior can be caused in two different ways: the hypnotized way and the normal, willful way.

Perhaps the most entrancing of the trance theories are those that point out the resemblance of hypnosis to brain states like those of sleep, sleep-walking, and relaxation (Edmonston 1981). The proponents of most of the trance theories would be happy to learn that recent studies of brain processes in hypnosis have suggested some key differences between the brain state of the hypnotizable subject in trance and not in trance. Although brain activity in trance is not very much like brain activity in sleep, it does seem to differ from that of the waking state. Evidence from neuropsychological research using various brain scan methods and measures of brain electrical activity indicates that hypnosis prompts unique patterns (Crawford, Knebel, and Vendemia 1998; Maquet et al. 1999; Rainville et al. 1999).

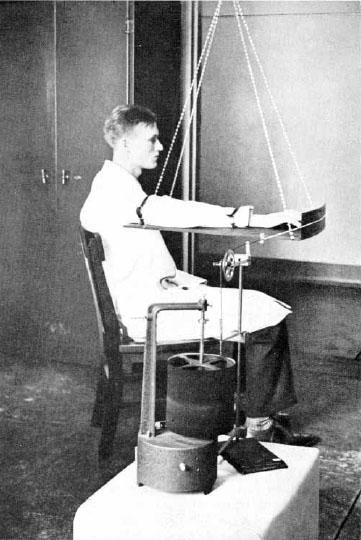

Figure 8.6

This arm suspension device allowed for precise measures of the degree of arm movement produced by ideomotor suggestions (“Think about your arm moving to the left”). Clark Hull, better known for his work on learning, applied scientific measurement in studying hypnosis as well. From Hull (1933). Courtesy Irvington Publishers.

A study of the influence of hypnosis on hallucinations provides a good example of the role of the brain in the hypnotic state (Szechtman et al. 1998). Highly hypnotizable subjects who were prescreened for their ability to hallucinate during hypnosis were tested while they lay in a PET (positron emission tomography) scanner. They first heard a recording of the line “The man did not speak often, but when he did, it was worth hearing what he had to say.” Then, they followed instructions to imagine hearing this line again, or they listened while the hypnotist suggested that the tape was playing once more, although it was not. This suggestion was expected to produce an auditory hallucination of the line, and these subjects reported that indeed it did. The PET scan revealed that the right anterior cingulate cortex was just as active while the subjects were hallucinating as when they were actually hearing the line. However, that brain area was not active while the subjects merely imagined the line. Hypnosis had apparently stimulated that area of the brain to register the hallucinated voice as real. It is likely that with further developments in brain imaging technology, much more will be known very soon about the brain substrate of hypnosis. For now, we can at least begin to see the outline of a brain state theory of hypnosis in these preliminary findings.

There is, however, another whole camp of hypnosis theories for which news of brain states is a major catastrophe. These are the theorists committed to various versions of the faking theory. The initial development of this theory came as a skeptical response to all trance talk and can be traced to the

role theory

of Sarbin (1950; Sarbin and Coe 1972). This account explains hypnosis in the same way one might explain the behavior of someone trying to be, say, a bank teller or to fit into any other social role. In this analysis, hypnosis is a performance, and some people are better performers than others. The best performers give performances that are convincing not only to their audience but to themselves. This theory suggests that early efforts at being hypnotized might be conducted only with much secret-keeping and conscious deception, and perhaps later replaced by more well-learned role enactment and less need for conscious duplicity. A highly trained bank teller, for instance, need not work each day while rehearsing “I must try to act like a bank teller, I must try to act like a bank teller.” With practice, this comes naturally along with the appropriate thoughts and even mental states. Hypnotic subjects learn their roles, and the faking becomes second nature.

6

A version of role theory by Barber (1969) draws on the observation that hypnotic behavior is often no more extreme than behavior in response to strong social influence, as in the snake-touching and acid-throwing examples. This

task motivation

theory says that people will do the odd things they find themselves doing in hypnosis whenever they are sufficiently motivated by social influence to perform such actions. Like role theory, this explanation says people are performing the hypnotic behaviors voluntarily. A related theory, labeled

social psychological

(Spanos 1986),

sociocognitive

(Wagstaff 1991), or

social cognitive

theory (Kirsch and Lynn 1998), draws upon both the role theoretic and task motivation ideas to suggest that people do hypnotic behaviors and report experiencing hypnotic mental states because they have become involved in social situations in which these behaviors and reports are highly valued. The idea is that the abridgement of reported conscious will that occurs in hypnosis arises not because of a reduction in willed action but as a result of strong social influences that promote the alteration of the report. Some versions of this theory suggest that full-tilt faking is not needed because the social influences often help people to develop imagery consistent with the suggestion, and this then aids them in experiencing involuntariness (Lynn, Rhue, and Weekes 1990).