The Illusion of Conscious Will (47 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

3.

The use of passes in hypnosis was particularly popular later in its history and still enjoys a certain popularity in an alternative health care technique called “healing hands” or “therapeutic touch” (e.g., Macrae 1987). Practitioners, most often nurses or other health care workers, have developed a detailed ideology surrounding the practice that unfortunately includes occult themes of which it is easy to be skeptical.

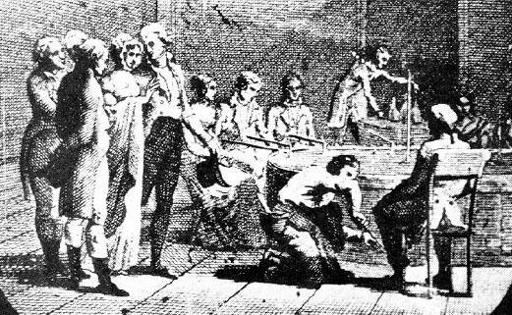

Figure 8.1

Group assembled for a mesmeric session. Participants seated at the

baquet

already have iron rods in hand, whereas standing spectators are talking about how much the fellow at the far left looks like George Washington. From Hull (1933).

The neophytes usually did not feel anything unless Mesmer himself came to magnetize them. For the more experienced patients, there were different types of reaction. Some would laugh, sweat, yawn, shiver; most of them had bowel movements, a sure sign of the effect of the magnetism, though this appears to have been the result of ingesting cream of tartar, a light laxative. . . . In a small proportion of patients, the effects were more intense. They shouted, cried, fell asleep, or lost consciousness. They sweated profusely; laughter and shivers became convulsive. In all this, Mesmer appeared like the conductor of an orchestra. With his glass or iron rod, he directed the ensemble. (Laurence and Perry 1988, 59)

Mesmer’s magnetism became a popular sensation and spread rapidly through France and Europe, developing a large following of practitioners (

fig. 8.2

). The idea became a well-developed cultural knowledge system in short order, just like the current widespread “sleeeeeepy” understanding of hypnosis. This no doubt helped in the implementation of the key procedures of induction—the sequential agreement process and the agreement to be influenced. The sequential agreement process was subtle in Mesmer’s approach, but we know that patients came to him with hopes of being healed of a variety of complaints, that they had heard of his successes, and that they paid him in advance for his services (Winter 1998). Sitting by the plumber’s nightmare

baquet

and allowing the mesmerist to make passes are initial steps to which people assented on the way to their bizarre behavior. No doubt, the presence of a company of people being magnetized helped to secure the success of the process as well, as more experienced patients served as models for the less experienced and all served as expectant audiences for one another.

Figure 8.2

Mesmeric passes. From Dupotet (1862).

Mesmer’s success was not dependent on his ability to make people convulse, of course, but on the cures he produced through his methods. Beyond all the strange behavior of his subjects was an underlying tendency to follow suggestions for the relief of symptoms—pain such as headache or backache, some cases of paralysis, blindness, lameness, and other complaints. His flourishes had the effect of influencing the expression of symptoms that are traditionally viewed as

hysterical

in origin— physical complaints without clear physical cause. Later, the psychiatrist Jean Charcot employed hypnotic techniques more like modern ones to much the same end and became famous for his treatment of hysterical symptoms (Ellenberger 1970). Pierre Janet and Sigmund Freud, in turn, each used varieties of hypnosis among the same sorts of patients, creating cures or rearrangements of symptoms by the use of suggestion (Showalter 1997).

Many of the most unusual hypnotic induction techniques depend on just the sorts of preparatory experiences evident in mesmerism. Hypnotic induction that seems instantaneous is commonly seen among faith healers, for example, when a belief system and a worship service provide the context of sequential agreement in which a single touch is enough to produce hypnotic effects. You may have come across the faith healer Benny Hinn on late-night TV, for example, putting people into trances by merely pushing them down by the forehead. Abell (1982) describes this particular move in the case of a Pentecostal church meeting:

Whether it is at the prayer line for persons seeking physical healing, or at the altar where a person is seeking the Holy Ghost, a significant stimulus . . . is “the push.” . . . As a potential convert is facing the minister, the minister will grip the convert’s forehead . . . [and] slightly (but very significantly) push the convert backwards. It is usually enough of a push that the potential convert will fall over backwards if he does not quickly attempt to regain his balance. . . . So the potential convert is forced both to take a step backwards as quickly as possible and to jerk his head and trunk forward. . . . It is precisely at the moment of the jerk that potential converts often go into a trance—dancing and quivering rapidly and violently, often accidentally hitting people and even falling down. (132-133)

The speedy induction through “the push” bears some resemblance to the fast inductions that occur among people who have had prior hypnosis. A hypnotist may specifically suggest this, saying, “You will wake up now, but later when I give you a special signal, when I say, ‘Relax,’ you will very quickly relax back into your deepest hypnotic trance.” This expedient makes the next hypnotic session take less time to initiate. Such rapid reinduction is one form of posthypnotic suggestion, the technique whereby people are given suggestions during hypnosis that they then perform later (sometimes unconsciously) when they return to a waking state. A rapid reinduction strategy is also used in stage hypnosis, as people who have been hypnotized earlier may be approached again during the show for what appears to be their first induction and be instantaneously hypnotized for the audience with one prearranged gesture or word (McGill 1947). The hypnotist says, “

Be

the dog,” and suddenly the audience member is down on all fours yipping.

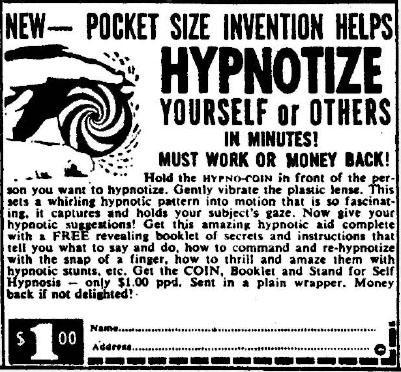

Hypnotic induction procedures can differ widely because of the strong influence of expectation on the entire hypnotic process (Kirsch 1999). It may matter far less what the hypnotist does than just that the hypnotist is doing

something

that is expected to have some effect. Hypnosis may be another version of the placebo effect, a way in which people behave when they think something is going to have an influence on them. The various hypnosis gadgets available in the media back pages may be quite effective in their own way for this reason—merely because people suspect that they might work (

fig. 8.3

). Perhaps if people generally believed that clog dancing would effect hypnotic induction, people could be clogged into a trance.

Figure 8.3

One of many versions of the hypno-coin. These can be dangerous if swallowed. Courtesy of Terry O’Brien.

Hypnotic Susceptibility

The tendency to follow hypnotic suggestions as well as to experience a reduction in the sense of conscious will in hypnosis varies widely in the general population. There are virtuosos, and there are those who can’t or won’t carry the tune. Most of us are between these extremes; most people are susceptible enough so that some kinds of hypnotic effects can be produced in over half of the population. Only about 10 percent, however, fall into what might be called the highly susceptible range on tests such as the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility (Shor and Orne 1962) and the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (Hilgard 1965; Weitzenhoffer and Hilgard 1962). These scales are not questionnaires but instead are standard hypnotic inductions made up of a series of tests of behavioral responsiveness to induction and experienced involuntariness. These scales are correlated with each other and with other indications of the success of induction but are only moderately associated with other personality dimensions that would seem as though they ought to be indicative of hypnotizability.

To nobody’s surprise, for instance, hypnotic susceptibility is moderately correlated with the tendency to say yes in response to questionnaire items (what is called the acquiescence response set; Hilgard 1965). Susceptibility is also somewhat related to imagination (the ability to experience vivid visual imagery; Sheehan 1979) and to absorption (the tendency to become deeply absorbed in experience; Tellegen and Atkinson 1974). Susceptibility is also correlated with the self-prediction of hypnotizability—people who think they can be hypnotized often indeed can be hypnotized (Hilgard 1965). This finding is in line with the aforementioned principle that expecting to be hypnotized may be a key cause of becoming hypnotized (Council, Kirsch, and Grant 1996; Kirsch 1999).

That’s about it, however, for personality correlates of hypnotizability. There does not seem to be a strong relation between hypnotizability and any of the major dimensions of personality identified by standard personality inventories, or between hypnotizability and dimensions of psychopathology assessed by usual measures such as the MMPI (Hilgard 1965; Kihlstrom 1985). So, for example, hypnotizable people are no more likely than others to be emotional or neurotic. It turns out, too, that there is no clear gender difference in hypnotic susceptibility (Hilgard 1965) despite the greater representation of females in several of the dissociative disorders and practices. Although hypnotizability is very stable over time, showing very similar levels even over the course of twenty five years (Piccione, Hilgard, and Zimbardo 1989), the hypnotizable person is not an easily characterized individual.

These findings are disappointing for those who have tried to explain the phenomena of dissociation, such as spirit mediumship or multiple personality, by connection to hypnotizability. It is tempting to suspect that there is one kind of person who is responsible for all this spooky stuff. But, as it turns out, there is no appreciable relation between measures of dissociation (such as the Dissociative Experiences Scale; Bernstein and Putnam 1986) and hypnotic susceptibility (e.g., Faith and Ray 1994). This may be due to the lack of a unified “dissociative personality,” and the tendency instead for different dissociative experiences to happen to different people. The general absence of a relation between hypnotic susceptibility and most tests of psychopathology, in turn, is problematic for theorists who perceived a connection between the phenomena of hysteria and the occurrence of hypnotizability (Ellenberger 1970; Gauld 1992; Kihlstrom 1994; Showalter 1997). After all, the similarity of hysterical conversion reactions (blindness, paralysis, convulsions, anomalous pain) to the results of hypnosis led many clinical theorists over the years, such as Charcot, Janet, and Freud, to the conclusion that hysterics were hypnotizable and hypnotizables were hysterics. This does not seem to be the case.

Instead, it seems that the unusual pliability of the hypnotized subject allows such subjects to mimic various psychopathologies. As mentioned earlier in the discussion of dissociative identity disorder (

chapter 7

), many cases of multiple personality seem to have arisen through the use of hypnosis in therapy (Acocella 1999). It is not particularly difficult, in fact, to get hypnotically susceptible people to produce vivid symptoms of DID in one or a few hypnosis sessions. In one study, subjects under suggestion produced automatic writing that they could not decipher but that on further suggestion they could understand and translate in full (Harriman 1942). About 7 percent of subjects in another study were able to respond to suggestions to create a secondary personality, a personality for which the main personality was then amnesic (Kampman 1976). The remarkable flexibility of the hypnotized individual has created a serious confusion between psychopathology and what might be no more than the chronic result of

suggestions

of psychopathology.