The Illusion of Conscious Will (22 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

The use of these sensitive devices to detect ideomotor movements suggests that the movements are quite meager. The notion that ideomotor phenomena are relatively weak doesn’t seem to square, though, with the finding that people can sometimes read the ideomotor muscle movements of others. Without benefit of special equipment, a variety of stage performers have exhibited muscle reading that appears to involve communication through ideomotor action. One such performer is the mentalist (“the Amazing”) Kreskin. He often asked a sponsor of his performance to hide his paycheck in the auditorium. Then, as part of the act, he grasped that person’s hand and, after marching around the place a bit, uncovered the paycheck somewhere in the seats—amidst protestations from the sponsor that he had not tried to give the location away.

8

Early muscle-reading performers were described by Beard (1877; 1882) and Baldwin (1902).

In some cases, the muscle reader might not even be aware of the source of the input and could react to the target person’s movements entirely unconsciously. In “The control of another person by obscure signs,” Stratton (1921) described the case of Eugen de Rubini. This performer would read muscles by holding the end of a watchchain held by the subject. He could sometimes dispense with the chain entirely and just observe the person, yet locate places or objects the person was thinking about. Rubini often didn’t even seem to look at the person and professed little awareness of the precise cues he used to do this. Beard (1882) described another muscle reader: “Mr. Bishop is guided by the indications unconsciously given through the muscles of his subject—differential pressure playing the part of ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ in the childish game which these words signify. Mr. Bishop is not himself averse to this hypothesis, but insists that if it is the true one he does not act upon it consciously. He described his own feelings as those of dreamy abstraction or ‘reverie,’ and his finding a concealed object, etc., as due to ‘an impression borne in’ upon him” (33).

8

Kreskin (1991) tells his secrets in a book that recounts this and dozens of other tricks that indeed are at least moderately amazing. He also takes credit for the Chevreul pendulum, however, calling it the Kreskin pendulum, an amazing bit of self-aggrandizement. A box containing one of his fobs along with instructions and an answer board was marketed as

Kreskin’s ESP

by Milton-Bradley.

The elevation of muscle reading into stage performance suggests that it is a special talent, but this may not be the case at all. Muscle reading of some kind may well occur in many normal people and in normal situations, leading generally to our ability to coordinate our movements with others without having to think about it. James (1904) mentioned muscle reading not as a skilled performance, for example, but as a parlor amusement called “the willing game” in which even a naive participant could often discern another’s secret thoughts about a place or object and find it in this way. It seems fair to say at this point, then, that ideomotor actions can be detected in a variety of ways, from delicate instrumentation to the relatively unsophisticated expedient of holding hands.

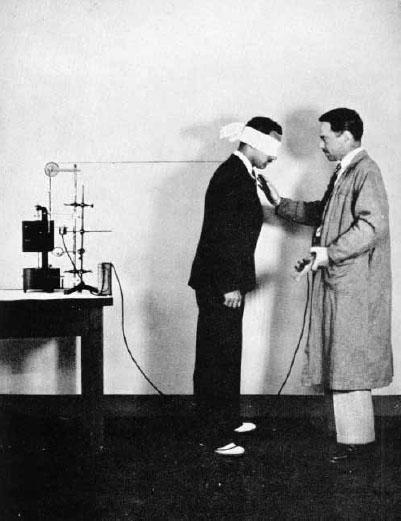

A clear ideomotor effect was shown in experiments Clark Hull (1933) conducted on what he called “unconscious mimicry.” He asked a young man to see how still he could stand with his eyes closed. Then, “under the preindent of placing him in the right position, a pin with a tiny hook at its end was deftly caught into the collar of his coat at the back. From this pin a black thread ran backward through a black screen to a sensitive recording apparatus. This apparatus traced faithfully on smoked paper . . . the subject’s forward and backward movements, but quite without his knowledge [

fig. 4.12

]. After he had been standing thus for about four minutes an assistant came apologetically into the room and inquired of the experimenter whether she could take her ‘test’ at once, as she had an appointment” (43).

The subject consented for her to go first and was permitted to open his eyes but cautioned not to move from his position. Hull recounted, “The assistant then took up a position in clear view of the subject, and just far enough from the wall so that she could not possibly touch it. She then proceeded to reach for the wall with all her might, giving free expression to her efforts by facial grimaces and otherwise. Meanwhile, the unconsciously mimetic postural movements of the unsuspecting subject were being recorded in detail. Sometimes subjects see through this ruse and then it commonly loses much of its effectiveness. But with a naive and unsuspicious subject there can usually be seen in the tracings evidence of a tendency to reproduce in his own body the gross postural movements of the person under observation. If the assistant reaches far forward, the subject sways forward slightly; if the assistant bends backward, the subject unconsciously sways backward” (43).

Figure 4.12

Body sway measurement device in Clark Hull’s laboratory. From Hull (1933). Courtesy Irvington Publishers.

Perhaps this kind of mimicry underlies a lot of unintentional coordination of action in everyday life. The unintended communication of movements may be involved in the way loving couples walk together, the way soldiers march, the way crowds swarm, and the way gestures and postures guide every social interaction. The young man with the hook on his collar seems to have been put into a position where his fleeting consciousness of the assistant’s movements influenced his own movements quite measurably, perhaps in a way that could have led to intentional movement later on. Had she been walking by his side and made a start toward the ice cream shop across the street, he could well have followed. The initial ideomotor action could launch him on a trajectory that his conscious intention might only overtake some moments later.

In fact, there is evidence that merely thinking about a

kind of person

can induce ideomotor mimicry of that person’s behavior. Bargh, Chen, and Burrows (1996) had college student participants fill out a scrambledsentence test that for some repeatedly introduced the idea of aging (with sentences that included words such as

wrinkled, grey, retired, wise,

and

old

). These people were thus primed with the stereotype of an old person, whereas other participants in the study did not receive this version of the test. As each participant left the experiment room, the person’s gait was measured surreptitiously. The individuals who been led to think about senior citizens

walked more slowly

than did those not primed with this thought. The idea of the action arose from the stereotype and so influenced the behavior directly, apparently without conscious will. Extensive postexperimental interviews suggested that the participants were not particularly conscious of the aged stereotype after the experiment. And even if they were, they were certainly not aware that this might suggest they should walk at a different speed, or for that matter that their walking speed was being assessed. Yet merely thinking of the kind of person who walks slowly seemed to be sufficient to induce shuffling.

Needless to say, this experiment has been quite controversial and has been followed by a number of further tests of this effect. In general, the phenomenon holds up very well (e.g., Dijksterhuis, Bargh, and Miedema 2001). Intriguing observations of this type have been made by Dijksterhuis and van Knippenberg (1998), for example, in experiments in which participants were asked to think about professors. When these individuals were then given a series of questions from a

Trivial Pursuit

game, they answered more items correctly than did participants given no professor prime. And, in turn, participants asked to think about soccer hooligans (who are stereotypically less than intelligent, particularly in the Netherlands, where this research was done) showed decreased performance on the trivia items. Dijksterhuis, Bargh, and Miedema (2001) also found that thinking of old age can prompt memory loss. And in studies of the tendency to be helpful, Macrae and Johnston (1998) observed that unscrambling sentences about helpfulness made people more likely to pick up dropped objects for an experimenter.

In these modern ideomotor studies, the idea that leads to an ideomotor action may or may not be conscious. The person may be asked to think about the idea for a while, may be exposed to the idea surreptitiously via a scrambled sentence task, or may be primed with the idea through brief subliminal exposures (Bargh and Chartrand 2000; Dijksterhuis, Bargh, and Miedema 2001). In the historical literature, this feature of ideomotor action also varies. In some of the examples (e.g., the person imagining an action in Jacobson’s experiments), the idea is perfectly conscious. In others (e.g., the participant in Jastrow and West’s automatograph study who is just listening to a metronome), the idea seems unlikely to be conscious. And in yet others (e.g., the person whose muscles are being read), the idea may be conscious but is probably accompanied by another conscious idea to the effect that the behavior should be inhibited (“I mustn’t give away the location”). All this suggests that the ideomotor influence of thoughts on actions may proceed whether the thoughts appear in consciousness or not—the thoughts merely need to be primed in some way.

9

The common thread through all the ideomotor phenomena, then, is not the influence of unconscious thoughts.

What ideomotor effects have in common is the apparent lack of conscious intention. In all these various observations, it is difficult to maintain that the person had a conscious intention to behave as he or she was seen to behave. Rather, the action appeared to come from thoughts directly without translation into an “I will do this” stage. People are not trying to clench their arms, walk slowly, keep rhythm, be especially helpful, guide the muscle reader,retrieve trivia, or the like. Rather, it appears that these actions seem to roll off in a way that skips the intention. Because of this, most people who have thought seriously about ideomotor effects have been led to propose that such effects are caused by a system that is distinct from the intentional system of behavior causation (Arnold 1946; Bargh and Chartrand 2000; Prinz 1987). If ideomotor action “must be under the

immediate

control of ideas that

refer to the action itself

” (Prinz 1987, 48), it can’t be under the person’s control and thus must be caused by something other than the will.

9.

Conscious primes don’t lead to ideomotor effects if people are told that the primes are expected by the experimenters to influence their behavior. This draws the person’s attention to the priming event and the behavior, and introduces a process of adjustment that eliminates the usual effect (Dijksterhuis, Bargh, and Miedema 2001). This effect harks back to James’ hypothesis that “conflicting notions” would block the occurrence of ideomotor effects.

Viewed in terms of the theory of apparent mental causation, however, ideomotor action takes on a different light. Rather than needing a special theory to explain ideomotor action,

we may only need to explain why ideomotor actions and automatisms have eluded the mechanism that produces the experience of will

. In this way of thinking, ideomotor action could occur by precisely the same kinds of processes that create intentional action but in such a way that the person’s usual inference linking the thought and action in a causal unit is obstructed. The surprising thing about ideomotor action, then, is not that the behavior occurs—behavior occurs with conscious and unconscious prior thoughts all the time—but rather that the behavior occurs without the experience of conscious will. Automatisms could flow from the same sources as voluntary action and yet have achieved renown as oddities because each one has some special quirk that makes it difficult to imbue with the usual illusion of conscious will. Automatism and ideomotor action may be windows on true mental causation as it occurs without apparent mental causation.

Conditions of Automatism

Now that we have a nice collection of automatisms, it is time to start collecting our wits. We need to examine the commonalities among the various automatisms to learn how and why they happen. To do this, we consider in turn each of several

conditions of automatism

—variables or circumstances that enhance the occurrence of automatism by clouding the perception of will. In what follows, we explore characteristics of the people who perform automatisms and, more to the point, the situations that generate automatisms in anyone, to see how the principles of priority, consistency, or exclusivity are breached in each case.

Dissociative Personality

The most common explanation for automatisms is the idea that they only happen to certain people—an explanation that might be called the

odd person theory

. Because the automatisms involve strange behaviors, and because people who perform strange behaviors are quickly assigned personal qualities consistent with those behaviors by the rest of us, by far the most frequent explanation of automatisms is that the person who does them is odd or abnormal. (This is why I was so relieved that I didn’t have to start walking like a duck.) Certainly, there are people who do seem unusually susceptible to certain automatisms—the spirit mediums, for example, or talented automatic writers. And, beyond this, there are cases of automatisms associated with serious mental disorders or brain damage that have gained great notoriety in the history of abnormal psychology.