The Illusion of Conscious Will (20 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

5.

One planchette speller, Pearl Curran, began experimenting alone with a Ouija board in 1912. After a year of practice and increasing involvement, she began to receive communications from a personality calling herself Patience Worth, allegedly a woman who had lived in the seventeenth century.Worth “dictated” an enormous quantity of literary compositions, including poems, essays, and novels, a number of which were subsequently published.The works were writ-ten in varieties of old English dialects that had never been spoken (Yost 1916).

Another possibility is that the presence of others makes the individual less likely to rehearse conscious intentions. Knowing that others are at least partly responsible, the person may lend his own intentions less than the usual amount of attention. So the action may seem to arise without prior thought. It may even be that when a nonself source is in view, this neglect of preview thoughts leads the individual to become less inclined to monitor whether the action indeed implements his own conscious thoughts. There may be a kind of social loafing (Latané, Williams, and Harkins 1979) in the generation and use of consciousness of action plans. Such a tendency to ignore or even suppress one’s own conscious contribution to a group product may be part of the production of social behaviors other than automatisms as well.

We should note one further aspect of the Ouija phenomenon that is perhaps its most remarkable characteristic. People using the board seem irresistibly drawn to the conclusion that some sort of unseen agent—beyond any of the actual people at the board—is guiding the planchette movement. Not only is there a breakdown in the perception of one’s own contribution to the talking board effect but a theory immediately arises to account for this breakdown: the theory of outside agency. In addition to spirits of the dead, people seem willing at times to adduce the influence of demons, angels, and even entities from the future or from outer space, depending on their personal contact with cultural theories about such effects. Even quite skeptical people can still be spooked by the idea of working with the board, worried that they might be dealing with unfathomable and potentially sinister forces. Hunt’s (1985) book about Ouija is subtitled

The Most Dangerous Game,

exemplifying exactly this kind of alarm. The board clearly has a bad reputation, abetted in large part by cultural myths and religious ideologies that have created scary ways of constructing and interpreting forms of outside agency. The head-spinning, frost-breathing demon possession in

The Exorcist

started with a seemingly innocent talking board.

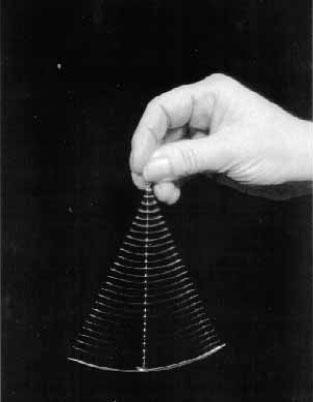

Chevreul Pendulum

The hand-held pendulum has long been used for divining, ostensibly obtaining messages from the gods. The pendulum is usually a crystal or other fob on a string or chain and is held without any intentional swinging (

fig. 4.7

). Its movement is read in various ways. A popular current notion is that it will move in a circle over the belly of a woman pregnant with a girl but in a straight line when the infant is a boy, apparently as a result of its extensive knowledge of phallic symbolism. Carpenter (1888) and James (1904) both remarked that when a person is thinking about the hour of the day and swings a ring by a thread inside a glass, it often strikes the hour, like the chime of a clock, even while the person has no conscious sense of doing this on purpose. And our fourth-century Roman friend Hilarius, mentioned earlier, was actually using a pendulum along with his letter board when he tested the Emperor’s sense of humor (Chevreul 1833). The use of the pendulum for answering questions or testing properties of objects, sometimes called radiesthesia, has traditionally attracted a small following of adherents (Zuzne and Jones 1989).

Figure 4.7

Chevreul pendulum. This one seems to be moving very vigorously, so it may be an intentional movement posed for the camera. Unintentional pendulum movements are typically more subtle. Courtesy Eduardo Fuss.

The French chemist Michel Chevreul did such a lovely job of debunking the occult interpretation of pendulum movement that he ended up lending his name to the phenomenon—the Chevreul pendulum. It seems that chemists of his time had been using pendulums to assay the metal content of ores and had developed intricate theories of just how the pendulum would move in response to various metals. Chevreul (1833) observed that this movement only occurred if the operator was holding the pendulum in hand and, further, looking at it. There seemed to be nothing special about the pendulum itself or its relation to the ore. Rather, the pendulum moved in response to the unconscious responses of the operator, directed in some unknown way by the operator’s perception of its movement.

Pendulum movement qualifies as an automatism because of the strong sense most operators express that they are not moving the pendulum on purpose. Well over half the population of individuals I’ve seen try the pendulum do get clearly unintentional movements. All you need to do is hold the pendulum, watch it carefully, and think about a particular pattern of movement (e.g., back and forth toward you, or in a circle). Without any intention on your part, the pendulum will often move just as you’ve anticipated. The effect is strong enough to make one under-stand how people may feel compelled to invent theories of supernatural forces or spirits responsible for the swing. Without a sense of conscious will to account for the movement, other agents become potential sources.

Modern research on Chevreul pendulum effects (Easton and Shor 1975; 1976; 1977) substantiates the basic characteristics of this phenomenon. It seems to happen particularly when one is looking at the pendulum and imagining a course of movement but trying not to move. This effect may be the simplest and most vivid demonstration we have of the translation of thought into movement without the feeling of doing. Carpenter (1888) summed it up as “a singularly complete and satisfactory example of the general principle, that, in certain individuals, and in a certain state of mental concentration, the

expectation

of a result is sufficient to determine—without any voluntary effort, and even in opposition to the Will (for this may be honestly exerted in the attempt to keep the hand perfectly unmoved)—the Muscular movements by which it is produced” (287).

On toying with the pendulum for a while, it is difficult to escape the idea that the pendulum is simply hard to operate. The perceived involuntariness of the movement seems to derive from thought/action inconsistency arising in the sheer unwieldiness of the pendulum. Moving one’s hand in one direction produces an impulse to the pendulum in the opposite direction, so the control of the movement is like trying to write while looking at one’s hand in a mirror. And once a movement gets started, it seems difficult to know just what needs to be done to dampen it. How do you stop a pendulum that is swinging in an oval? Even slight errors of timing can cause one’s attempts to stop the pendulum to start it instead, and in just the wrong direction. The lack of consistency between intention and action of the pendulum promotes the sense that the pendulum’s movement is not controlled by the will.

The other intuition that is hard to dispel once one has played with a pendulum is that it often seems to do the opposite of what one desires. Trying to keep it from swinging to and fro, for example, seems to be a good way to nudge it toward just such movement. In studies in my laboratory (Wegner, Ansfield, and Pilloff 1998), this possibility has been ob-served in detail. Participants were specifically admonished

not

to move the pendulum in a particular direction, and the pendulum’s movement was observed by a video camera. The repeated finding was that this suggestion not to move in a certain direction yielded significant movement in exactly the forbidden direction, and that this tendency was amplified if the person was given a mental load (counting backward from 1,000 by 3s) or a physical task (holding a brick at arm’s length with the other arm). These observations illustrate the possibility that the desire not to perform an action can ironically yield that action. Given that a person is consciously intending not to perform the action, ironic effects like this one opposing the intention are particularly apt cases of automatism.

Dowsing

The use of a dowsing or divining rod to find water or other underground treasures also qualifies as an automatism. To do this, a person usually grasps the two branches of a forked twig, one in each hand, with the neck (or bottom of the Y) pointing upward at about a 45° angle. The forked twig is placed under tension as a result, such that certain slight movements of the wrists or forearms will cause the stick to rotate toward the ground. When this happens, the automatism is usually interpreted as a sign of water below. This interpretation turns out to be superstitious, however, because controlled investigations reveal that there is no reliable association of the stick’s movement with water, minerals, or anything else under the ground beyond what might be expected on the basis of the dowser’s personal judgment (Barrett and Besterman 1926; Foster 1923; Randi 1982; Vogt and Hyman 1959). Although the dowser clearly moves the stick, and uses knowledge about when and where this should be done, he or she professes a lack of the feeling of doing this (

fig. 4.8

).

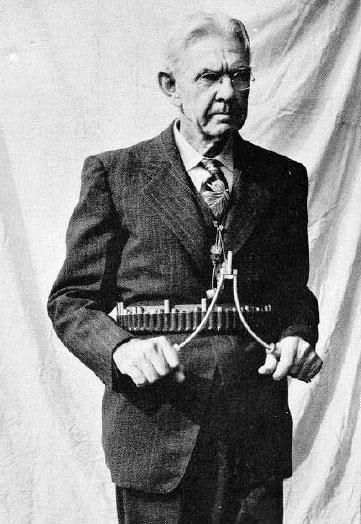

Figure 4.8

Clarence V. Elliott, of Los Angeles, demonstrates dowsing equipment of his own design. The forked metal rod has a detachable top into which can be fitted samples of the substance sought; the containers are carried, ready to use, in a cartridge belt. From Vogt and Hyman (1959).

The psychological interpretation of this effect involves several parts, as detailed by Vogt and Hyman (1959).

6

First, the person who gets started dowsing usually has an experienced dowser as a guide and gets drawn in initially by imitating the master’s activities. Second, there are various cues to the presence of water underground (e.g., green areas, gravel washes) that anyone who has thought about this very much might pick up. Third, the dowser undoubtedly does experience some unexpected and involuntary movement, largely because the rod is unwieldy and leads to confusion about what role the dowser is playing in moving it. With his muscles straining slightly against the rod, an awkward tension is set up that indeed induces involuntary action, in the same way that one’s leg braced at an uncomfortable angle underneath an airline tray table will sometimes suddenly straighten out, usually during a meal. (Although why anyone would actually want to locate airline food is a mystery.) And finally, dowsers like all people are good at overestimating the success of their activities, and often take credit for performance that is actually no better than random. In 1982 the renowned skeptic (“the Amazing”) James Randi tested several professional dowsers with an elaborate underground plumbing system that could reroute the flow of water through pipes without their knowledge, and though they located the flow at no better than a chance level, they nonetheless left the experiment proclaiming triumph. Automatism plays a role in dowsing, then, but is really only part of the psychological show.

Another dowsing device is the L-rod or swing rod (

fig. 4.9

). This is an L-shaped wire or metal rod held in the hand like a pistol, sometimes with a tube as a handle that allows the long end to swivel in different directions. The beauty of this device is that it points not down or up but left and right, so one can follow it around to find things. Normally, the dowser holds two, one in each hand, and they may signal that it is time to stop by crossing. (If they both suddenly stick into the ground and stay there, it may mean that the dowser has fallen down and can’t get up.)

6.

Vogt and Hyman (1959) describe this in a clever fictional passage about how a naive observer, Jim Brooks (of course), gets involved in dowsing. Vogt and Hyman’s is by far the best account anywhere of why dowsing doesn’t work and of why some people are so convinced that it does. This book is perhaps the best model in existence of the careful scientific analysis of supernatural claims.