The Illusion of Conscious Will (19 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

2.

This is Gertrude Stein, who subsequently wrote

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas

(1933) and many other works. Her writings are not noted for their content but rather for the use of sounds and rhythms of words, and it is possible that she may have produced them automatically.

This case resembles alien hand syndrome and could indeed have a neuropsychological basis (e.g., Joseph 1986). After all, the automatism in Smith’s hand included not only unconsciousness of action and loss of the feeling of doing but also anesthesia. Then again, it was au courant in Smith’s day for people to experience limb anesthesia, often as a symptom of hysteria, the psychiatric disorder frequent in the nineteenth century that has largely disappeared (Veith 1970). Given this cultural fashion, such anesthesia may have been Smith’s response to a strong belief that anesthesia could happen in automatic writing. Although it is tempting to speculate on remarkable cases like Smith’s, the still more remarkable fact is that thousands of other people working their pencils or planchettes have also experienced some degree of automatic writing, albeit less dramatically. How should we understand these more commonplace experiences?

One possibility is that awareness of action dims in automatic writing, just as it seems to subside with practiced or habitual actions in general. When we can do something well, distractions can happen and we can lose track of our action even while it carries on.

3

The few laboratory studies of automatic writing in normal individuals attempted to produce the effect by giving people distracting tasks (such as reading or arithmetic) and then having them practice writing during such a task (Downey and Anderson 1915; Solomons and Stein 1896; Stein 1898). These endeavors met with mixed success because even extended practice does not entirely erase the consciousness of action. If anything, with practice or distraction, the consciousness of action becomes elective or optional rather than necessary. More modern experiments along this line by Spelke, Hirst, and Neisser (1976) revealed that “the introspections offered by the subjects . . . were chaotic and inconsistent: Sometimes they knew exactly what they were writing, sometimes they were not aware of having written at all” (Neisser 1976, 104). Under laboratory conditions with normal participants, then, the consciousness of writing comes and goes.

3.

This was observed even in the heyday of automatic writing, for example, in studies of skilled telegraphers (Bryan and Harter 1899). As formulated by Jastrow (1906, 42), this broad principle of action states, “At the outset each step of the performance is separately and distinctly the object of attention and effort; and as practice proceeds and expertness is gained . . . the separate portions thereof become fused into larger units, which in turn make a constantly diminishing demand upon consciousness.”

Automatic writing is facilitated by confusion about the source of one’s movement. Alfred Binet (1896) described a method for producing automatic writing that involves such

movement confusion

and that also qualifies as a cute trick to play on the gullible. What you do is ask a person to think of a name and then tell her that you will make her write the name. Have the person look away while you grasp her hand lightly, “as one teaches a child to write” (228). Then, saying, “I will write it,” you begin simply to move your hand, slightly jiggling the person’s hand. Binet claimed frequent success in stimulating a person to write the name even while the person claimed that Binet was producing the movement. I’ve tried this a few times with people I’ve thought might be willing to accept the claim that I could read their minds, and have found in this informal sampling that the technique produces the imagined name about one third of the time. This seems particularly effective with children. Some of my victims do believe that I’ve made them write the name, whereas others correctly perceive that they wrote it while I just served as their personal jiggler.

These curious effects are, unfortunately, still more in the nature of parlor games than sturdy, reproducible scientific phenomena. There is simply not enough systematic research on automatic writing to allow a full understanding of its nature and causes. What we have at present is a collection of observations that point to the possibility that some people can lose either conscious awareness of what is written, or the feeling of doing, or both when they try to do so as they write. We don’t have enough collected observations of the effect to have a strong conception of when and why it happens.

Some of the murkiness surrounding the topic of automatic writing must be the conceptual difficulty surrounding the

perception of a lack of consciousness

. How can people tell that they are not conscious of some-thing? How can they tell if they’ve written automatically? This puzzle is nicely described by Julian Jaynes (1976): “Consciousness is a much smaller part of our mental life than we are conscious of, because we can-not be conscious of what we are not conscious of. . . . How simple that is to say; how difficult to appreciate!It is like asking a flashlight in a dark room to search around for something that does not have any light shining upon it. The flashlight, since there is light in whatever direction it turns, would have to conclude that there is light everywhere. And so consciousness can seem to pervade all mentality when it actually does not” (23). Jaynes rightly observes that, by definition, we cannot know what lies beyond our consciousness.

In the case of automatic writing, people can really only report a lack of consciousness of their action of writing after they have finished, when they are ostensibly conscious once again. They might then base their report of lack of consciousness during the writing on several different after-the-fact cues. They might notice that they don’t recall what was said; they might notice that they don’t recognize what was said when they read it; they might notice that things were written that they don’t believe they would write or that they don’t believe are true; or perhaps, even if they were conscious of the content before or during the writing, they might notice that while they recall or recognize the writing, they don’t recall the experience of consciously willing their act of writing. The scientific study of this phenomenon could begin in earnest if it focused on the nature and interplay of these various cues people may use to judge the automaticity of their writing.

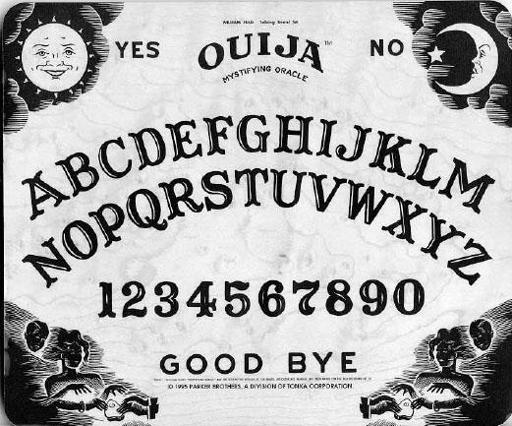

Ouija Board

The face of the Ouija board is as familiar to many people as the face of a Monopoly board, and it is fitting that both are copyrighted by Hasbro, Incorporated (

fig. 4.4

). The name is often attributed to a conjunction of the French

oui

and German

ja,

making it a yes-yes board (although if it were spelled Wee-Jah, it could be a pairing of Scottish with Jamaican patois, meaning “little God”). The use of an alphabet or symbol board for divining is traced by some to antiquity, with versions attributed to early Greek, Roman, Chinese, and Native American societies (Hunt 1985). One origin story involves the use of a “little table marked with the letters of the alphabet,” which in A.D. 371 apparently got one unlucky Roman named Hilarius tortured on a charge of magical operations against the Emperor (Jastrow 1935). Apparently the Emperor didn’t think it was so funny.

Figure 4.4

A modern Ouija board. © Hasbro, Inc.

The version of the Ouija board in use these days, complete with a three-legged planchette, was initially manufactured in 1890 by Charles Kennard, and then soon after by William Fuld and the Baltimore Talking Board Company.

4

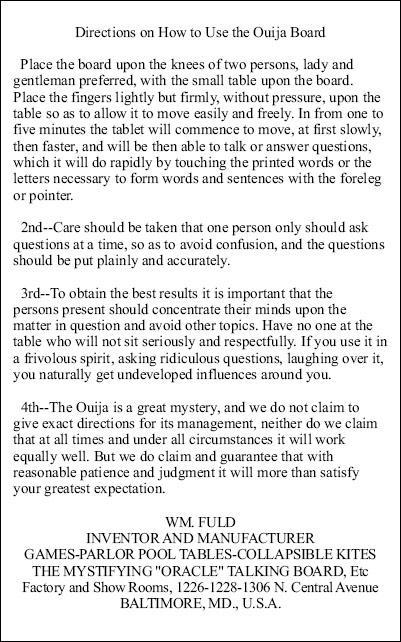

The instruction calls for the users (usually two, as in

fig. 4.5

), but more are allowed) to concentrate on a question as they place fingertips on the planchette and then to wait for movement (

fig. 4.6

). What people usually do, however, is to start moving in a circular or random pattern around the board quite on purpose, waiting then for unintended direction or relevant pauses of the movement. The experience of people who have tried this is that it may or may not work, but that when it does, the sense of involuntariness regarding the planchette’s moves can be quite stunning.

Figure 4.5

Norman Rockwell’s painting of this Ouija board graced the cover of the

Saturday Evening Post

on May 1, 1920. A young couple in love, conjuring up a demon. Courtesy of Dr. Donald Stoltz.

4.

A Web site by Eugene Orlando,

The Museum of Talking Boards,

features photos of a variety of boards and planchettes. My thanks to Orlando for a personal tour of his board collection and for his insights on the history and operation of the talking board.

Figure 4.6

These instructions were printed on the back of a board manufactured in 1902.

Of course, the first option for an explanation here is deception. One mystified person might experience involuntariness while another is in fact mischievously moving the planchette around on purpose. It is impossible, of course, to sense whether part of the movement coming from the other person is intended. Some people report planchette spelling and answering that occurs even when they are performing solo, however, much as in automatic writing, and this suggests that there can be an experience of automatism with the Ouija that transcends mere deception.

5

The fact that Ouija board automatism is more likely with groups than with individuals is significant by itself. Even if we assume that some proportion of the people in groups are actually cheating, there still seems to be a much greater likelihood of successful automatism in these social settings. James (1889, 555) observed that in the case of automatic writing, “two persons can often make a planchette or bare pencils write automatically when neither can succeed alone.” This is, of course, a usual feature of the experience of table turning and tilting as well (Carpenter 1888). The standard Ouija procedure takes advantage of this social effect, and it is interesting to consider the possible mechanisms for this social magnification of automatism.

One possibility is that in groups, people become confused about the origins of their own movement. We’ve already seen this happening in the Binet “mind-reading” effect, when one person jiggles the hand of another and so prompts automatic writing. James (1889, 555) remarked that “when two persons work together, each thinks the other is the source of movement, and lets his own hand freely go.” The presence of others may introduce variability or unpredictability into the relation between one’s own intentions and actions. The exclusivity principle of apparent mental causation would suggest that co-actions reduce the individual’s tendency to assume a relation between his thoughts and the observed movements because these movements may have been produced by the other person. The consistency principle, in turn, would also predict ambiguities or reductions in the experience of will because the other person’s contributions could introduce trajectories to the group movement that are not consistent with the individual’s initial thought about the movement. Difficulty in tracking the relation between intentions and observed actions—what we have called movement confusion—is likely to reduce the experience of will.