The Illusion of Conscious Will (14 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

Figure 3.3

Participant and confederate move the computer mouse together in the

I Spy

experiment by Wegner and Wheatley (1999).

That is, they each would rate how much they had intended to make each stop, independent of their partner’s intentions. The participant and con-federate made these ratings on scales that they kept on clipboards in their laps. Each scale consisted of a 14-centimeter line with end points “I al-lowed the stop to happen” and “I intended to make the stop,” and marks on the line were converted to percent intended (0-100).

The participant and confederate were told that they would hear music and words through headphones during the experiment. Each trial would involve a 30-second interval of movement, after which they would hear a 10-second clip of music to indicate that they should make a stop. They were told that they would be listening to two different tracks of an audiotape, but that they would hear music at about the same times and should wait a few seconds into their music before making the stops to make sure they both were ready. Participant and confederate were also told that they would hear a word over the headphones on each trial, ostensibly to provide a mild distraction, and that the reason for the separate audio tracks was so that they would hear different words. To emphasize this point, the experimenter played a few seconds of the tape and asked the participant and confederate which word they heard in their headphones. The confederate always reported hearing a different word from the participant. Thus, participants were led to believe that the words they heard were not heard by the confederate.

The words served to prime thoughts about objects on the screen for the participant (e.g.,

swan

). The confederate, on the other hand, heard neither words nor music, but instead heard instructions to make particular movements at particular times. For four of the trials, the confederate heard instructions to move to an object on the screen followed by a countdown, at which time the confederate was to stop on that object. These

forced

stops were each timed to occur midway through the participant’s music. Each of the stops (e.g., to land on the swan) was timed to occur at specific intervals from when the participant heard the corresponding word (

swan

). The participant thus heard the word consistent with the stop either 30 seconds before, 5 seconds before, 1 second before, or 1 second after the confederate stopped on the object. By varying the timing, priority was thus manipulated. Each of these four stops was on a different object. The four forced stops were embedded in a series of other trials for which the confederate simply let the participant make the stops. For these

unforced

stops, the participant heard a word 2 seconds into the music whereas the confederate did not hear a word. The word correponded to an object on the screen for about half of these trials and was something not appearing on the screen for the others.

An initial analysis of the unforced stops was made to see whether participants might naturally stop on the objects that were mentioned. The confederate would have only had a random influence on stops for these trials, as he or she was not trying to guide the movement. If the cursor did stop on items that the participant had heard mentioned, it would suggest that the participant might also have played some part in the forced stops, and it was important to assess whether he had. Distances between stops and objects on the screen were computed for all unforced stops (all trials in which the confederate heard no instruction and simply let the participant make the stop). The mean distance between the stop and an object on the screen (e.g., dinosaur) was measured separately for stops when that object was the mentioned word and for stops when the mentioned word was something not shown on the screen (e.g.,

monkey

). The mean distance between stop and object when the word referred to the object was 7.60 centimeters, and this was not significantly closer than the distance of 7.83 centimeters when the word did not refer to the object. Thus, simply hearing words did not cause participants to stop on the items. The forced stops created by the confederate were thus not likely to have been abetted by movement originated by the participant.

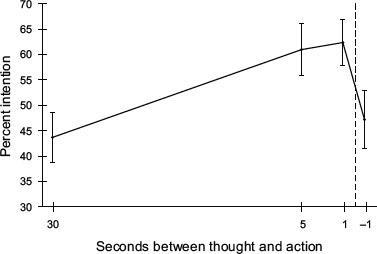

Nonetheless, on the forced stops a pattern of perceived intention emerged as predicted by the priority principle. Although there was a tendency overall for participants to perceive the forced stops as somewhat intended (mean intentionality = 52 percent), there was a marked fluctuation in this perception depending on when the word occurred. As shown in

figure 3.4,

perceived intentionality was lower when the object-relevant word appeared 30 seconds before the forced stop, increased when the word occurred 5 seconds or 1 second before the stop, and then dropped again to a lower level when the word occurred 1 second following the stop. As compared to trials when thought consistent with the forced action was primed 30 seconds before or 1 second after the action, there was an increased experience of intention when the thought was primed 1 to 5 seconds before the forced action. The mean intention reported on all the unforced stops—when participants were indeed free to move the cursor anywhere—was 56 percent, a level in the same range as that observed for the forced stops in the 1-second and 5-second priming trials.

Figure 3.4

Participants in the

I Spy

experiment rated their personal intention to stop on an object as higher when they had heard the name of the object 5 seconds or 1 second before they were forced to stop on it than when they heard the name 30 seconds before or 1 second after the forced stop. From Wegner and Wheatley (1999).

In postexperimental interviews, participants reported sometimes searching for items on screen that they had heard named over their headphones. Perhaps this sense of searching for the item, combined with the subsequent forced stop on the item, was particularly helpful for prompting the experience of intending to stop on the item. It is difficult to discern from these data just what feature of having the object in mind prior to the forced stop produced the sense of will, but it is clear that the timing of the thought in relation to the action is important. When participants were reminded of an item on the screen just 1 second or 5 seconds before they were forced to move the cursor to it, they reported having performed this movement intentionally. Such reminding a full 30 seconds before the forced movement or 1 second after the movement yielded less of this sense of intentionality. The parallel observation that participants did not move toward primed objects on unforced trials suggests that participants were unlikely to have contributed to the movement on the forced trials. Apparently, the experience of will can be created by the manipulation of thought and action in accord with the principle of priority, and this experience can occur even when the person’s thought cannot have created the action.

The Consistency Principle

When one billiard ball strikes another, the struck ball moves in the same general direction that the striking ball was moving. We do not perceive causality very readily if the second ball squirts off like squeezed soap in a direction that, by the laws of physics, is inconsistent with the movement of the first ball (Michotte 1962). Now, causality need not be consistent in reality. Very tiny causes (a struck match) can create very great effects (a forest in cinders), or causes of one class of event (a musical note) can create effects of some other class (a shattered goblet). It is sometimes difficult to say just what consistency might be in physical causation, for that matter, because there are so many dimensions on which a cause and effect might be compared.

Causes Should Relate to Effects

When it comes to the psychological principles that influence the

perception

of causality, however, consistency is a fundamental canon. Big causes are assumed to be necessary to create big effects, for example, and bad people are seen as more likely to have done bad things. People are far more likely to perceive causality when they can appreciate some meaningful connection between a candidate causal event and a particular effect (Einhorn and Hogarth 1986; Nisbett and Ross 1980). John Stuart Mill (1843) complained long ago that this bias, the “prejudice that the conditions of a phenomenon must

resemble

the phenomenon . . . not only reigned supreme in the ancient world, but still possesses almost undisputed dominion over many of the most cultivated minds” (765). Perceiving causality through consistency is particularly prevalent in children, in whom it even has a name—phenomenism (Piaget 1927; Laurendeau and Pinard 1962). And anthropologists have described such tendencies in other cultures in terms of “laws of sympathetic magic” (Mauss 1902; Nemeroff and Rozin 2000). Educated adults in North America, for ex-ample, are inaccurate in throwing darts at a picture when it portrays a person they like (Rozin, Millman, and Nemeroff 1986). By the principle of consistency, this would suggest that they themselves are causing harm to their loved one, nd this undermines their aim.

The principle of consistency operates in apparent mental causation because the thoughts that serve as potential causes of actions typically have meaningful associations with the actions. A thought that is perceived to cause an act is often the name of the act, an image of the act, or a reference to its execution, circumstance, or consequence (Vallacher and Wegner 1985). Thoughts in the form of intentions, beliefs, or desires about the action are all likely to be semantically related to the act. Consistency of thought and act depends, then, on a cognitive process whereby the thoughts occurring prior to the act are compared to the act as subsequently perceived. When people do what they think they were going to do, there exists consistency between thought and act, and the experience of will is enhanced. (“I thought I’d have a salad for lunch, and here I am eating it.”) When they think of one thing and do another—and this inconsistency is observable to them—their action does not feel as willful. (“I thought I’d have a salad for lunch, and here I am with a big plate of fries.”)

The consistency phenomenon has come up a lot in studies of the perception of contingency between behavior and outcomes (Alloy and Tabachnik 1984; Jenkins and Ward 1965). These are studies in which a person presses a button repeatedly, for example, to see if it makes money come out of a slot. As anyone who has gambled will tell you, people doing things that could result in success or failure will typically envision success (“Baby needs a new pair of shoes!”). Thus, when success occurs, the consistency between the prior thought and the observed action produces an experience of will. So, for example, Langer and Roth (1975) found that people were likely to perceive that they controlled a chance event when they achieved a large number of initial successes in predicting that event. Jenkins and Ward (1965) similarly found that the perception that one is causing a successful outcome is enhanced merely by the increased frequency of that outcome. And it makes sense, then, that depressed individuals, who think less often of success (“Baby needs a new reason to cry”)—are not as likely as others to overperceive control of successful outcomes (Alloy and Abramson 1979). It might even be that when people really

do

expect the worst and so think about it as they act, they might have a perverse experience of conscious will when the worst happens. The depressed person may come away from many of life’s little disasters thinking, “I cause bad things to happen.”

Consistency sometimes allows us to begin feeling that we are willing the actions of others. This was illustrated in a pair of experiments in which participants were given the opportunity to perceive someone else’s hands in place of their own (Wegner, Winerman, and Sparrow 2001). In these studies, each participant was asked to wear a robe and stand before a mirror. Another person of the same sex (either another participant or an experimenter) standing behind the participant then placed his or her arms around the participant and out through holes in the front of the robe. The hands wore gloves, and the participant was thus given the odd experience of seeing another person’s hands in place of his or her own. This setup resembles a form of pantomime sometimes called “helping hands.”

The person standing in back then followed a series of some twenty five tape-recorded instructions directing the hands’ actions—to clap three times, make a fist with the right hand, and so on. Participants who were asked afterward to rate the degree to which they felt they were control-ling the hands under these conditions were slightly amused by the circum-stance, but they didn’t express much of a feeling of control (about 1.5 on a 7-point rating scale). However, when participants were played the tape of the instructions during the actions, their experience of control in-creased notably (to around 3 on the scale). Although they didn’t claim full control, consistent previews led them to experience a distinct enhancement of the feeling that they were operating hands that belonged to another person.