The Illusion of Conscious Will (13 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

Studies of how people perceive external physical events (Michotte 1954) indicate that the perception of causality is highly dependent on these features of the relation between the potential cause and potential effect. The candidate for the role of cause must come first or at least at the same time as the effect, it must yield movement that is consistent with its own movement, and it must be unaccompanied by rival causal events. The absence of any of these conditions tends to undermine the perception that causation has occurred. Similar principles have been derived for the perception of causality for social and everyday events (Einhorn and Hogarth 1986; Kelley 1972; 1980; McClure 1998) and have also emerged from analyses of how people and other organisms respond to patterns of stimulus contingency when they learn (Alloy and Tabachnik 1984; Young 1995). The application of these principles to the experience of conscious will can explain phenomena of volition across a number of areas of psychology.

4.

If the branch moved

regularly

just before you thought of it moving, you could get the willies. In this event, it would seem as though the branch somehow could anticipate your thoughts, and this would indeed create an odd sensation. Dennett (1991) recounted a 1963 presentation of an experiment by the British neurosurgeon W. Grey Walter in which patients had electrodes implanted in the motor cortex, from which amplified signals were used to advance a slide projector. The signals were earlier than the conscious thought to move to the next slide, so patients experienced the odd event of the slide advancing just before they wanted it to advance. Dennett swears this report is not apocryphal, but unfortunately this work was never published and seemingly has not been replicated by others since. A discovery of this kind would be absolutely stunning, and I’m thinking Grey Walter may have been pulling his colleagues’ legs.

The Priority Principle

Causal events precede their effects, usually in a timely manner. The cue ball rolls across the table and taps into the 3 ball, touching the 3 ball just before the 3 ball moves. If they touched after the movement or a long time before it, the cue ball would not be perceived as causing the 3 ball to roll. And perhaps the most basic principle of the sense of will is that conscious thoughts of an action appearing just before an act yield a greater sense of will than conscious thoughts of an action that appear at some other time—long beforehand or, particularly, afterwards. The thoughts must appear within a particular window of time for the experience of will to develop.

The Window of Time

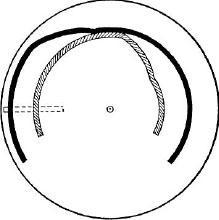

Albert Michotte (1954) was interested in what causation looks like, what he called the phenomenology of causality. To study this, he devised an animation machine for showing people objects that move in potentially causal patterns. The device was a disk with a horizontal slot, through which one could see lines painted on another disk behind it. When the rear disk was rotated, the lines appeared as gliding objects in the slot, and the movement of these could be varied subtly in a variety of ways with different line patterns (

fig. 3.2

).

Michotte’s most basic observation with this device was the “launching effect.” When one of the apparent objects moved along and appeared to strike another, which then immediately began to move in the same direction even while the first one stopped or slowed down, people perceived a causal event: the first object had launched the second. If the second object sat there for a bit after the first touched it, however, and only

then

began moving, the sense that this was a causal event was lost and the second object was perceived to have started moving on its own. Then again, if the second object began to move before the first even came to touch it, the perception of causation was also absent. The second object seemed to have generated its own movement or to have been launched by some-thing unseen. The lesson, then, is that to be perceived as truly a cause, an event can’t start too soon or too late; it has to occur just before the effect.

Figure 3.2

Michotte’s (1954) launching disk. This disk rotated behind a covering disk through which the lines could be seen only through a slot. When the lined disk turned counterclockwise, the solid object appeared to move to the right and hit the crosshatched object, launching it to the right. Courtesy Leuven University Press.

These observations suggest that the experience of will may also depend on the timely occurrence of thought prior to action. Thought that occurs too far in advance of an action is not likely to be seen as the cause of it; a person who thinks of dumping a bowl of soup on her boss’s head, for example, and then never thinks about this again until suddenly doing it some days later during a quiet dinner party, is not likely to experience the action as willful. Thought that occurs well after the relevant action is also not prone to cue an experience of will. The person who discovers having done an act that was not consciously considered in advance—say, getting in the car on a day off and absently driving all the way to work—would also feel little in the way of conscious will.

Somewhere between these extreme examples exist cases in which conscious will is regularly experienced. Little is known about the parameters of timing that might maximize this experience, but it seems likely that thoughts occurring just a few seconds before an action would be most prone to support the perception of willfulness. Thoughts about an action that occur earlier than this and that do not then persist in consciousness might not be linked with the action in a perceived causal unit (Heider 1958) because thought and act were not in mind simultaneously. Slight variations in timing were all that was needed in Michotte’s experiments to influence quite profoundly whether the launching effect occurred and causation was perceived.

The time it usually takes the mind to wander from one topic to another could be the basic limit for experiencing intent as causing action. The mind does wander regularly (Pöppel 1997; Wegner 1997). For ex-ample, a reversible figure such as a Necker cube (the standard doodle of a transparent cube) that is perceived from one perspective in the mind’s eye will naturally tend to change to the other in about 3 seconds (Gomez et al. 1995). Such wandering suggests that a thought occurring less than 3 seconds prior to action could stay in mind and be linked to action, whereas a thought occurring before that time might shift to something else before the act (in the absence of active rehearsal, at any rate) and so undermine the experience of will (Mates et al. 1994).

Another estimate of the maximum interval from intent to action that could yield perceived will is based on short-term memory storage time. The finding of several generations of researchers is that people can hold an item in mind to recall for no longer than about 30 seconds without rehearsal, and that the practical retention time is even shorter when there are significant intervening events (Baddeley 1986). If the causal inference linking thought and act is primarily perceptual, the shorter (3-second) estimate based on reversible figures might be more apt, whereas if the causal inference can occur through paired representation of thought and act in short-term memory, the longer (30-second) estimate might be more accurate. In whatever way the maximum interval is estimated, though, it is clear that there is only a fairly small window prior to action in which relevant thoughts must appear if the action is to be felt as willed.

This brief window reminds us that even long-term planning for an action may not produce an experience of will unless the plan reappears in mind just as the action is performed. Although thinking of an action far in advance of doing it would seem to be a signal characteristic of a premeditated action (Brown 1996; Vallacher and Wegner 1985), the present analysis suggests that such distant foresight yields less will perception than does immediately prior apprehension of the act. In the absence of thought about the action that occurs just prior to its performance, even the most distant foresight would merely be premature and would do little to promote the feeling that one had willed the action. In line with this suggestion, Gollwitzer (1993) has proposed that actions that are intended far in advance to correspond with a triggering event (“I’ll go when the light turns green”) may then tend to occur automatically with-out conscious thought, and thus without a sense of volition, when the triggering event ensues.

The priority principle also indicates that thoughts coming after action will not prompt the experience of will. But, again, it is not clear just how long following action the thought would need to occur for will not to be experienced. One indication of the lower bound for willful experience is Libet’s (1985) observation that in the course of a willed finger movement, conscious intention precedes action by about 200 milliseconds. Perhaps if conscious thought of an act occurs past this time, it is perceived as following the act, or at least as being too late, and so is less likely to be seen as causal. Studies of subjective simultaneity have examined the perceived timing of external events and actions (McCloskey, Colebatch et al. 1983), but research has not yet tested the precise bounds for the perception of consecutiveness of thought and action. It seems safe to say, however, that thoughts occurring some seconds or minutes after action would rarely be perceived as causal and could thus not give rise to an experience of will during the action.

There are, of course, exceptions to the priority principle. Most notably, people may sometimes claim their acts were willful even if they could only have known what they were doing after the fact. These exceptions have been widely investigated for the very reason that they depart from normal priority. These are discussed in some depth in

chapter 5

. In the meantime, we can note that such findings indicate that priority of intent is not the only source of the experience of will and that other sources of the experience (such as consistency and exclusivity) may come forward to suggest willfulness even when priority is not present. Now let’s look at a study that creates an illusion of will through the manipulation of priority.

The I Spy Study

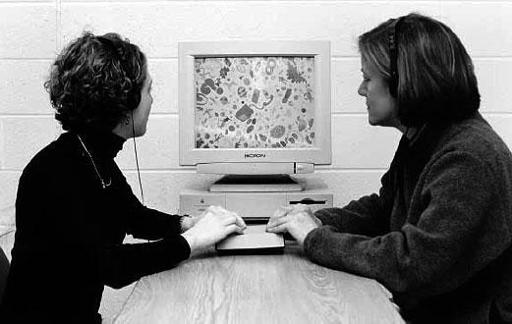

If will is an experience fabricated from perceiving a causal link between thought and action, it should be possible to lead people to feel that they have performed a willful action when in fact they have done nothing. Wegner and Wheatley (1999) conducted an experiment to learn whether people will feel they willfully performed an action that was actually per-formed by someone else when conditions suggest their own thought may have caused the action. The study focused on the role of priority of thought and action, and was inspired in part by the ordinary household Ouija board. The question was whether people would feel they had moved a Ouija-like pointer if they simply thought about where it would go just in advance of its movement, even though the movement was in fact produced by another person.

Each participant arrived for the experiment at about the same time as a confederate who was posing as another participant. The two were seated facing each other at a small table, on which lay a 12-centimeter-square board mounted atop a computer mouse. Both participant and confederate were asked to place their fingertips on the side of the board closest to them (

fig. 3.3

) so that they could move the mouse together. They were asked to move the mouse in slow sweeping circles and, by doing so, to move a cursor around a computer screen that was visible to both. The screen showed a “Tiny Toys” photo from the book

I Spy

(Marzollo and Wick 1992), picturing about fifty small objects (e.g., dinosaur, swan, car).

5

The experimenter explained that the study was to investigate people’s feelings of intention for acts and how these feelings come and go. It was explainedthatthepairweretostopmovingthemouseevery30secondsorso, and that they would rate each stop they made for personal intentionality.

5.

In some early trials, we attempted to use a standard Ouija board and found enough hesitation among even our presumably enlightened college student participants (“There are evil spirits in that thing”) that we subsequently avoided reference to Ouija and designed our apparatus to appear particularly harmless. No evil spirits were detected in the

I Spy

device.