The Illusion of Conscious Will (10 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

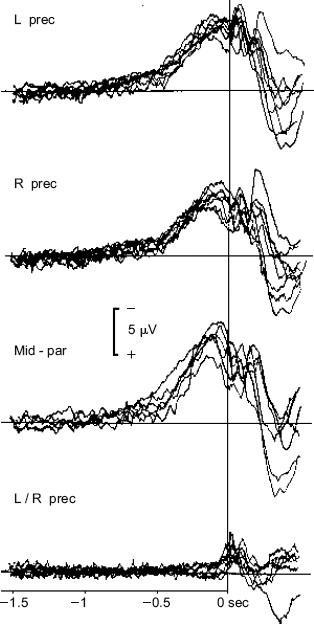

At some arbitrary time in the next few seconds, please move your right index finger. That’s correct, please perform a consciously willed action. Now, here’s an interesting question: What was your brain up to at the time? In an elaborate experiment, Kornhuber and Deecke (1965) arranged to measure this event in a number of people by assessing the electrical potentials on the scalp just before and after such voluntary finger movements. Continuous recordings were made of electrical potentials at several scalp electrodes while the experimenter waited for the subject to lift that finger. The actual point when the finger moved was measured precisely by electromyography (EMG, a sensor to detect muscle movement), and this was repeated for as many as 1,000 movements per experiment with each subject. Then, using the movement onset as a reference point, the average scalp electrical potentials could be graphed for the time period surrounding all those voluntary actions.

Et voilà—the spark of will! Brain electrical activity was found to start increasing about 0.8 seconds before the voluntary finger movement. Kornhuber and Deecke dubbed this activity the

readiness potential

(RP). As shown in

figure 2.7

, this RP occurs widely in the brain—in the left and right precentral regions (spots a bit above and forward of the ear, corresponding to the motor area) and in the midparietal region (top of the head), as shown in the upper three panels. This negative electrical impulse peaks about 90 milliseconds before the action and then drops a bit in the positive (downward) direction before the action. The ratio of the left to right potentials shown in the fourth panel also reveals a bit of a blip about 50 milliseconds before the action on the left side of the motor area of the brain. Just before the right finger moves, the finger and hand motor area contralateral to that finger—the area that controls the actual move-ment—is then activated. This blip has been called the

movement potential

(Deecke, Scheid, and Kornhuber 1969). It seems as though a general readiness for voluntary action resolves into a more localized activation of the area responsible for the specific action just as the action unfolds.

Figure 2.7

The brain potentials measured by Deecke, Grozinger, and Kornhuber (1976). Each graphic curve represents one experiment. The top three panels show the development of the readiness potential (RP) at three scalp locations, and the bottom panel shows the movement potential in the difference between left and right in the precentral motor area associated with finger movement. The RP onset is about 800 milliseconds before the voluntary finger movement, whereas the movement potential onset is only 50 milliseconds before the movement.

The discovery of the RP for voluntary action electrified a number of brains all over the world. The excitement at having found a brain correlate of conscious will was palpable, and a number of commentators exclaimed breathlessly that the science of mind had reached its Holy Grail. John Eccles (1976; 1982) applauded this research, for example, and suggested that these findings showed for the first time how the conscious self operates to produce movement. He proposed,

Regions of the brain in liaison with the conscious self can function as extremely sensitive detectors of consciously willed influences. . . . As a consequence, the willing of a movement produces the gradual evolution of neuronal responses over a wide area of frontal and parietal cortices of both sides, so giving the readiness potential. Furthermore, the mental act that we call willing must guide or mold this unimaginably complex neuronal performance of the liaison cortex so that eventually it “homes in” on to the appropriate modules of the motor cortex and brings about discharges of their motor pyramidal cells. (1976, 117)

What Eccles overlooked in his enthusiasm was that in this study the conscious self had in fact never been queried. The study simply showed that brain events occur reliably before voluntary action.

When exactly in this sequence does the person experience

conscious

will? Benjamin Libet and colleagues (1983; Libet 1985; 1993) had the bright idea of asking people just this question and invented a way to time their answers. Like participants in the prior RP experiments, participants in these studies were also asked to move a finger spontaneously while wearing EMG electrodes on the finger and scalp EEG electrodes for RP measurement. And as in the prior studies the participants were asked to move the finger at will: “Let the urge to act appear on its own any time without any preplanning or concentration on when to act” (627). In this case, however, the participant was also seated before a visible clock. On the circular screen of an oscilloscope, a spot of light revolved in a clockwise path around the circumference of the screen, starting at the twelve o’clock position and revolving each 2.65 seconds—quite a bit faster than the second hand of a real clock. A circular scale with illuminated lines marked units around the edge, each of which corresponded to 107 milliseconds of real time. The participant’s task was simply to report for each finger movement where the dot was on the clock when he experienced “

conscious awareness of ‘wanting’ to perform

a given self-initiated movement” (627).

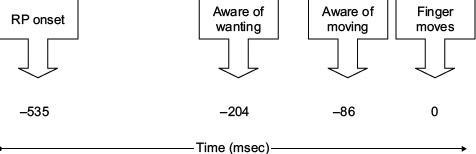

Figure 2.8

Time line of events prior to voluntary finger movement, in research by Libet et al. (1983).

The researchers called these measurements the W series (for wanting) and also took some other key measurements for comparison. For an M (movement) series, instead of asking the participant to report where the dot was when he became consciously aware of wanting to move, the participant was asked for the location of the dot when he became aware of actually moving. And in an S (stimulation) series, the participant was simply asked to report the clock position when a stimulus was applied to the back of his hand.

The results were truly noteworthy, although in some sense this is exactly what you would have to expect: The conscious willing of finger movement occurred at a significant interval

after

the onset of the RP but also at a significant interval

before

the actual finger movement (and also at a significant interval before the awareness of movement). The time line for the RP, W, M, and actual movement events is shown in

figure 2.8

. These findings suggest that the brain starts doing something first (we don’t know just what that is). Then the person becomes conscious of wanting to do the action. This would be where the conscious will kicks in, at least, in the sense that the person first becomes conscious of trying to act. Then, and still a bit

prior

to the movement, the person reports be-coming aware of the finger actually moving.

6

Finally, the finger moves.

6

. This odd finding indicates that people are aware of moving some significant small interval before they actually move. Haggard, Newman, and Magno (1999) and McCloskey, Colebatch et al. (1983) reported results consistent with this, and Haggard and Magno (1999) found that the timing of this awareness of movement can be influenced by transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Libet and colleagues suggested that the S series could be used as a guide to estimating how long any hand-to-brain activity might take. It took about 47 milliseconds for people to report being consciously aware of a stimulus to the hand, so Libet reasoned it might be useful to subtract this number from the W and M series values to adjust for this part of the process. This doesn’t really change the overall conclusion; it just moves the “aware of wanting” time to 157 milliseconds and the “aware of moving” time to 39 milliseconds. One other quibble: You may have noticed that the RP in this study occurred later (535 milliseconds) than the one in Kornhuber and Deecke’s experiment (approximately800 milliseconds). This is because Libet made a special point of asking participants to mention if they had done any preplanning of the finger movement and eliminated those instances from the analysis. In a separate study, Libet, Wright, and Gleason (1982) had learned that the RP occurred as much as a second or two earlier on trials when participants were allowed to plan for their movement, so the conscious will study avoided this by emphasizing spontaneous, unplanned movements.

The conclusion suggested by this research is that the experience of conscious will kicks in at some point

after

the brain has already started preparing for the action. Libet sums up these observations by saying that “the initiation of the voluntary act appears to be an unconscious cerebral process. Clearly, free will or free choice of whether

to act now

could not be the initiating agent, contrary to one widely held view. This is of course also contrary to each individual’s own introspective feeling that he/she consciously initiates such voluntary acts; this provides an important empirical example of the possibility that the subjective experience of a mental causality need not necessarily reflect the actual causative relationship between mental and brain events” (Libet 1992, 269).

Recounting Libet’s discovery has become a cottage industry among students of consciousness (Dennett 1991; Harth 1982; Nørretranders 1998; Spence 1996; Wegner and Bargh 1998), and for good reason. Although there have only been a few replications of the research itself, because this is difficult and painstaking science (Keller and Heckhausen 1990; Haggard and Eimer 1999), the basic phenomenon is so full of implications that it has aroused a wide range of comments, both supportiveandcritical (seethecommentariespublishedfollowing Libet 1985; also, Gomes 1998). Many commentators seem to agree that it is hard to envision conscious will happening well before anything in the brain starts clicking because that would truly be a case of a ghost in the machine. The common theme in several of the critiques, however, is the nagging suspicion that somehow conscious will might at least share its temporal inception with brain events. Some still hope, as did John Eccles, that conscious will and the RP leading to voluntary action would at least be synchronous. That way, although we might not be able to preserve the causal priority of conscious will, the conscious will might still be part of the brain train, all of which leaves the station at once. Yet this is not what was observed. In what happened, the brain started first, followed by the experience of conscious will, and finally followed by action.

We don’t know what specific unconscious mental processes the RP might represent.

7

These processes are likely to be relevant in some way to the ensuing events, of course, because they occur with precise regularity in advance of those events. Now, the ensuing events include both the experience of wanting to move

and

the voluntary movement. The RP could thus signal the occurrence of unconscious mental events that produce both the experience of wanting to move and the occurrence of actual movement. This possibility alerts us to the intriguing realization that conscious wanting, like voluntary action, is a mental event that is caused by prior events. It seems that conscious wanting is not the beginning of the process of making voluntary movement but rather is one of the events in a cascade that eventually yields such movement. The position of conscious will in the time line suggests perhaps that the experience of will is a link in a causal chain leading to action, but in fact it might not even be that. It might just be a loose end—one of those things, like the action, that is caused by prior brain and mental events.

7

. Keller and Heckhausen (1990) found that RPs also were detectable for stray, unconscious finger movements. The technology underlying RP measurement can’t distinguish, then, between the conscious and voluntary movements studied by Libet and any sort of movement, even an unconscious one. We just know that an RP occurs before actions (Brunia 1987). RPs do not occur for involuntary movements such as tics or reflex actions (e.g., Obeso, Rothwell, and Marsden 1981).