The Illusion of Conscious Will (6 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

11

. Oliver Sacks (1994) has documented the intriguing details of a life without mind perception. He recounts his interviews with Temple Grandin, an astonishing adult with autism who also holds a Ph.D. in agricultural science and works as a teacher and researcher at Colorado State University. Her attempts to understand human events—even though she lacks the natural ability to pick up the nuances of human actions, plans, and emotions—impressively illustrate the unusual skill most people have in this area yet take for granted. Grandin has cultivated this ability only through special effort and some clever tricks of observation.

We’re now getting close to a basic principle about the illusion of conscious will. Think of it in terms of lenses. If each person has two general lenses through which to view causality—a mechanical causality lens for objects and a mental causality lens for agents—it is possible that the mental one

blurs

what the person might otherwise see with the mechanical one. The illusion of conscious will may be a misapprehension of the mechanistic causal relations underlying our own behavior that comes from looking at ourselves by means of a mental explanatory system. We don’t see our own gears turning because we’re busy reading our minds.

The Illusion Exposed

Philosophers and psychologists have spent lifetimes thinking about how to reconcile conscious will with mechanistic causation. This problem— broached in various ways as the mind/body problem, free will vs. determinism, mental vs. physical causation, and the analysis of reasons vs. causes—has generated a literature that is immense, rich, and shocking in its inconclusiveness (Dennett 1984; Double 1991; Earman 1986; Hook 1965; MacKay 1967; Uleman 1989). What to do? The solution explored in this book involves recognizing that the distinction between mental and mechanical explanations is something that concerns everyone, not only philosophers and psychologists. The tendency to view the world in

both

ways, each as necessary, is what has created in us two largely incompatible ways of thinking. When we apply mental explanations to our own behavior-causation mechanisms, we fall prey to the impression that our conscious will causes our actions. The fact is, we find it enormously seductive to think of ourselves as having minds, and so we are drawn into an intuitive appreciation of our own conscious will.

Think for a minute about the nature of illusions. Any magician will tell you that the key to creating a successful illusion is to make “magic” the easiest, most immediate way to explain what is really a mundane event. Harold Kelley (1980) described this in his analysis of the underpinnings of magic in the perception of causality. He observed that stage magic involves a

perceived causal sequence

—the set of events that appears to have happened—and a

real causal sequence

—the set of events the magician has orchestrated behind the scenes. The perceived sequence is what makes the trick. Laws of nature are broken willy-nilly as people are sawed in half and birds, handkerchiefs, rabbits, and canes appear from nothing or disappear or turn into each other and back again.

The real sequence is often more complicated than the perceived sequence, but many of the real events are not perceived. The magician needs special pockets, props, and equipment, and develops wiles to misdirect audience attention from the real sequence. In the end, the audience observes something that seems to be simple, but in fact it may have been achieved with substantial thought, preparation, and effort on the magician’s part. The lovely assistant in a gossamer gown apparently floating effortlessly on her back during the levitation illusion is in fact being held up by a 600-pound pneumatic lift hidden behind a specially rigged curtain. It is the very simplicity of the illusory sequence, the shorthand summary that hides the magician’s toil, that makes the trick so compelling. The lady levitates. The illusion of conscious will occurs in much the same way.

The real causal sequence underlying human behavior involves a massively complicated set of mechanisms. Everything that psychology studies can come into play to predict and explain even the most innocuous wink of an eye. Each of our actions is really the culmination of an intricate set of physical and mental processes, including psychological mechanisms that correspond to the traditional concept of will, in that they involve linkages between our thoughts and our actions. This is the empirical will. However, we don’t see this. Instead, we readily accept a far easier explanation of our behavior: We intended to do it, so we did it.

The science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke (1973) remarked that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” (21). Clarke was referring to the fantastic inventions we might discover in the future or in our travels to advanced civilizations. However, the insight also applies to self-perception. When we turn our attention to our own minds, we are faced with trying to understand an unimaginably advanced technology. We can’t possibly know (let alone keep track of) the tremendous number of mechanical influences on our behavior because we inhabit an extraordinarily complicated machine. So we develop a shorthand, a belief in the causal efficacy of our conscious thoughts. We believe in the magic of our own causal agency.

The mind is a system that produces

appearances

for its owner. Things appear silver, for example, or they appear to have little windows, or they appear to fly, as the result of how the mind produces experience. And if the mind can make us “experience” an airplane, why couldn’t it produce an experience of

itself

that leads us to think that it causes its own actions? The mind creates this continuous illusion; it really doesn’t

know

what causes its own actions. Whatever empirical will there is rumbling along in the engine room—an actual relation between thought and action—might in fact be totally inscrutable to the driver of the machine (the mind). The mind has a self-explanation mechanism that produces a roughly continuous sense that what is in consciousness is the cause of action—the phenomenal will—whereas in fact the mind can’t ever know itself well enough to be able to say what the causes of its actions are. To quote Spinoza in

The Ethics

(1677), “Men are mistaken in thinking themselves free; their opinion is made up of consciousness of their own actions, and ignorance of the causes by which they are determined. Their idea of free-dom, therefore, is simply their ignorance of any cause for their actions” (pt. II, 105). In the more contemporary phrasing of Marvin Minsky (1985);“None of us enjoys the thought that what we do depends on processes we do not know; we prefer to attribute our choices to

volition, will,

or

self-control

. . . . Perhaps it would be more honest to say,

‘My decision was determined by internal forces I do not understand’

” (306).

2

Brain and Body

Conscious will arises from processes that are psychologically and anatomically distinct from the processes whereby mind creates action

.

The feeling we call volition is not the cause of the voluntary act, but simply the symbol in consciousness of that stage of the brain which is the immediate cause of the act.

T. H. Huxley,

On the Hypothesis That Animals Are Automata

(1874)

It is not always a simple matter to know when someone is doing something on purpose. This judgment is easy to make for animated cartoon characters because a lightbulb usually appears over their heads at this time and they then rear back and look quickly to each side before charging off to do their obviously intended and voluntary action. Often a cloud of dust remains. In the case of real people, however, knowing whether another person has done something willfully can be a detective exercise. In some of the most important cases, these things must even be decided by the courts or by warfare, and no one is really satisfied that the willfulness of actions judged after the fact is an accurate reflection of a person’s state at action onset. Perhaps we need a lightbulb over our head that flashes whenever we do something on purpose.

But how would the lightbulb know? Is there some place in the mind or brain that lights up just as we perform a consciously willed action, a place to which we might attach the lightbulb if we knew the proper wiring? Certainly, it often seems that this is the case. With most voluntary actions, we have a feeling of doing. This feeling is such a significant part of consciously willed acts that, as we have seen, it is regarded as part of their definition. Will is the feeling that arises at the moment when we do something consciously—when we know what it is we are doing, and we are in fact doing it. What is it we are feeling at this time? Is it a direct expression of a causal event actually happening somewhere in our mental or neural architecture? Or is it an inference we make about ourselves in the same way we make an inference about the cartoon character when we see the lightbulb?

We can begin to grasp some answers to such questions by examining the anatomical and temporal origins of the experience of will. Where does the experience of will come from in the brain and body? When exactly does it arrive? In this chapter we examine issues of where the will arises by considering first the anatomy of voluntary action—how it differs from involuntary action and where in the body it appears to arise. We focus next on the sensation of effort in the muscles and mind during action to learn how the perception of the body influences the experience of will, and then look directly at the brain sources of voluntary action through studies of brain stimulation. These anatomical travels are then supplemented by a temporal itinerary, an examination of the time course of events in mind and body as voluntary actions are produced. In the process of examining all this, we may learn where, when, and how we get the feeling that we’re doing things.

Where There’s a Will

Many modern neuroscientists localize the “executive control” portion of the mind in the frontal lobes of the brain (e.g., Stuss and Benson 1986; 1987). This consensus derives from a host of observations of what hap-pens in human beings (Burgess 1997; Luria 1966, Shallice 1988) and animals (Passingham 1993) when portions of the frontal lobes are damaged or missing. Such damage typically leads to difficulties in the planning or initiation of activity as well as loss of memory for ongoing activity. This interlinked set of specific losses of ability has been called the frontal lobe syndrome. A person suffering from this syndrome might be unable to plan and carry out a simple act such as opening a soda can, for example, or might find it hard to remember to do things and so be unable to keep a job.

1

This widely observed phenomenon suggests that many of the causal sequences underlying human action may be localized in brain structures just under the forehead. Brain-imaging studies also suggest that voluntary actions are associated with activity in the frontal region (Ingvar 1994; Spence et al. 1997). However, this sort of evidence tells us little about where the

experience

of will might arise.

1

Antonio Damasio (1994) retells the story of one man suffering such damage, Phineas P. Gage, who survived a blasting accident that sent a metal rod up through his left cheek and out the top of his head, destroying his left frontal lobe. Although Gage recovered physically, and indeed appeared to have suffered no change in his level of everyday intelligence, his life afterwards was marked by a series of poor plans, lost jobs, and broken relationships. Damasio attributes this to the loss of frontal lobe function.

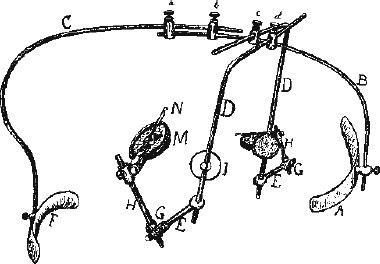

Figure 2.1

Bair’s (1901) device for measuring ear wiggling. It was clamped to the forehead (A) and the base of the neck (F), and the sensor (M) was rested on the ear.

Voluntary and Involuntary Systems

Let’s begin with the ears. Although the study of ear wiggling has never really taken off to become a major scientific field, a number of early experiments by Bair (1901) focused on how people learn this important talent. He constructed an ear wiggle measurement device (

fig. 2.1

) to assess the movement of the retrahens muscle behind the ear, tried it on a number of people, and found that the majority (twelve of fourteen in his study) couldn’t move their ears using this muscle. Some could wiggle by making exaggerated eyebrow movements, and I suppose a few were inspired to reach up and manipulate their ears with their hands. But, by and large, this was an action beyond willful control—at least at first.

An action that can’t be consciously willed is sort of a psychological black hole. Bair noticed that when people couldn’t move their ears as directed, they said they didn’t even feel they were doing anything at all. One reported, “It seemed like trying to do something when you have no idea how it is done. It seemed like willing to have the door open or some other thing to happen which is beyond your control” (Bair 1901, 500). Trying to wiggle your ears when you don’t know how is like trying to wiggle someone else’s ears from a distance. No matter how much you think about the desired movement, or how you go about thinking of it, those movements that are beyond voluntary control simply won’t happen—there seems to be

nothing to do.

This observation highlights what may be the simplest definition of voluntary or willful action, at least in people: A voluntary action is something a person can do when asked.

2