The Illusion of Conscious Will (3 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

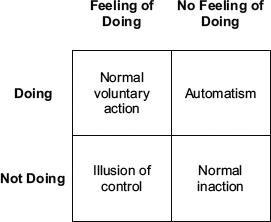

Such examples of the separation of action from the experience of will suggest that it is useful to draw a distinction between them.

Figure 1.3

shows what might be considered four basic conditions of human action—the combinations that arise when we emphasize the distinction between action and the sense of acting willfully. The upper left quadrant shows the expected correspondence of action and the feeling of doing—the case when we do something and feel also that we are doing it. This is the non-controversial case, or perhaps the assumed human condition. The lower right quadrant is also noncontroversial, the instance when we are not doing anything and feel we are not.

Figure 1.3

Conditions of human action.

The upper right quadrant—the case of no feeling of will when there is in fact action—encompasses the examples we have looked at so far. The movement of alien hands, the hypnotic suggestion of arm heaviness, and table turning all fit in this quadrant because they involve no feeling of doing in what appear otherwise to be voluntary actions. These can be classed in general as

automatisms

.

3

More automatisms are explored in later chapters. The forms they take and the roles they play in life are something of a subtext throughout this book. We should not fail to notice here, however, the other special quadrant of the table—cases of the

illusion of control

. Ellen Langer (1975) used this term to describe in-stances in which people have the feeling they are doing something when they actually are not doing anything.

4

When does this happen? The last time it happened to me was when I was shopping in a toy store with my family one Saturday. While my kids were taking a complete inventory of the stock, I eased up to a video game display and started fiddling with the joystick. A little monkey on the screen was eagerly hopping over barrels as they rolled toward him, and I got quite involved in moving him along and making him hop, until the phrase “Start Game” popped into view. I was under the distinct impression that I had started some time ago, but in fact I had been “playing” during a pre-game demo. Duped perhaps by the wobbly joystick and my unfamiliarity with the game, I had been fiddling for nothing, the victim of an illusion of control. And, indeed, when I started playing the game, I immediately noticed the difference. But for a while there, I was oblivious to my own irrelevance. I thought I was doing something that I really didn’t do at all.

3

. An automatism is not the same thing as an automatic behavior, though the terms arise from the same beginnings (first mentioned by Hartley 1749). An automatism has been defined as an apparently voluntary behavior that one does not sense as voluntary (Carpenter 1888; Janet 1889; Solomons and Stein 1896), and we retain that usage here. More generally, though, a behavior might be automatic in other senses—it could be uncontrollable, unintended, efficient, or performed without awareness, for instance (Bargh 1994; Wegner and Bargh 1998).

4

. This term is not entirely fitting in our analysis because the larger point to be made here is that all of the feeling of doing is an illusion. Strictly speaking, then, the whole left side of the table should be labeled illusory. But for our purposes, it is worth noting that the illusion is particularly trenchant when there is intention and the feeling of doing but in fact no action at all.

The illusion of control is acute in our interactions with machines, as when we don’t know whether our push of an elevator button or a Coke machine selection lever has done anything yet sense that it has. The illusion is usually studied with judgments of contingency (e.g., Matute 1996) by having people try to tell whether they are causing a particular effect (for example, turning on a light) by doing something (say, pushing a but-ton) when the button and the light are not perfectly connected and the light may flash randomly by itself. But we experience the illusion, too, when we roll dice or flip coins in a certain way, hoping that we will thus be able to influence the outcome. It even happens sometimes that we feel we have contributed to the outcome of a sporting event on TV just by our presence in the room (“Did I just jinx them by running off to the fridge?”).

The illusion that one has done something that one has not really done can also be produced through brute social influence, as illustrated in a study by Kassin and Kiechel (1996). These researchers falsely accused a series of participants in a laboratory reaction time task of damaging a computer by pressing the wrong key. All the participants were truly innocent and initially denied the charge, showing that they didn’t really

experience

damaging the computer. However, they were led later to remember having done it. A confederate of the experimenters claimed afterwards that she saw the participant hit the key or did not see the participant hit the key. Those whose “crime” was ostensibly witnessed became more likely to sign a confession (“I hit the ALT key and caused the pro-gram to crash. Data were lost.”), internalize guilt for the event, and even confabulate details in memory consistent with that belief—but only when the reaction time task was so fast that it made their error seem likely. We are not infallible sources of knowledge about our own actions and can be duped into thinking we did things when events conspire to make us feel responsible.

Most of the things we do in everyday life seem to fall along the “nor-mal” diagonal in

figure 1.3

. Action and the experience of will usually correspond, so we feel we are doing things willfully when we actually do them and feel we are not doing something when in truth we have not done it. Still, the automatisms and illusions of control that lie off this diagonal remind us that action and the feeling of doing are not locked together inevitably. They come apart often enough to make one wonder whether they may be produced by separate systems in the mind. The processes of mind that produce the experience of will may be quite distinct from the processes of mind that produce the action itself. As soon as we accept the idea that the will should be understood as an

experience

of the person who acts, we realize that conscious will is not inherent in action—there are actions that have it and actions that don’t.

The definition of will as an experience means that we are very likely to appreciate conscious will in ourselves because we are, of course, privy to our own experiences and are happy to yap about them all day. We have a bit more trouble appreciating conscious will in others sometimes, and have particular difficulty imagining the experience or exercise of conscious will in creatures to whom we do not attribute a conscious mind. Some people might say there is nothing quite like a human being if you want a conscious mind, of course, but others contend that certain non-human beings would qualify as having conscious minds. They might see conscious minds in dogs, cats, dolphins, other animals (the cute ones), certain robots or computers, very young children, perhaps spirits or other nonexistent beings.

5

In any event, the conscious mind is the place where will happens, and there is no way to learn whether an action has been consciously willed without somehow trying to access that mind’s experience of the action. We have the best evidence of an experience of conscious will in ourselves, and the second-best evidence becomes available when others communicate their experience of will to us in language (“I did it!”).

5

. Dennett (1996) discusses the problem of other minds very elegantly in

Kinds of Minds.

The Force of Conscious Will

Will is not only an experience; it is also a force. Because of this, it is tempting to think that the conscious experience of will is a direct perception of the force of will. The

feeling

that one is purposefully not having a cookie, for instance, can easily be taken as an immediate perception of one’s conscious mind

causing

this act of self-control. We seem to experience the force within us that keeps the cookie out of our mouths, but the force is not the same thing as the experience.

6

When conscious will is described as a force, it can take different forms. Will can come in little dabs to produce individual acts, or it can be a more long-lasting property of a person, a kind of inner strength or resolve. Just as a dish might have hotness or an automobile might have the property of being red, a person seems to have will, a quality of power that causes his or her actions. The force may be with us. Such will can be strong or weak and so can serve to explain things such as one person’s steely persistence in the attempt to dig a swimming pool in the backyard, for ex-ample, or another person’s knee-buckling weakness for chocolate. The notion of strength of will has been an important intuitive explanation of human behavior since the ancients (Charleton 1988), and it has served throughout the history of psychology as the centerpiece of the psychology of will. The classic partition of the mind into three functions includes cognition, emotion, and

conation

—the will or volitional component (e.g., James 1890).

The will in this traditional way of thinking is an explanatory entity of the first order. In other words, it explains lots of things but nothing explains it. As Joseph Buchanan described it in 1812, “Volition has commonly been considered by metaphysical writers, as consisting in the exertion of an innate power, or constituent faculty of the mind, denominated will, concerning whose intrinsic nature it is fruitless and unnecessary to inquire” (298). At the extreme, of course, this view of the will makes the scientific study of it entirely out of the question and suggests instead that it ought to be worshiped. Pointing to will as a force in a person that causes the person’s action is the same kind of explanation as saying that God has caused an event. This is a stopper that trumps any other explanation but that still seems not to explain anything at all in a predictive sense. Just as we can’t tell what God is going to do, we can’t predict what the will is likely to do.

7

6

. Wittgenstein (1974) complained about defining will in terms of experience, feeling that this by itself was incomplete.He noted that there is more to will than merely the feeling of doing: “The will can’t be a phenomenon, for whatever phenomenon you take is something that

simply happens,

something we undergo, not something we

do

. . . . Look at your arm and move it and you will experience this very vividly: ‘You aren’t observing it moving itself, you aren’t having an experience—not just an experience, anyway—you’re

doing

something’” (144).

The notion that will is a force residing in a person results in a further problem. Hume (1739) remarked on this problem when he described the basic difficulty that occurs whenever a person perceives causality in an object. Essentially, he pointed out that causality is not a property inhering in objects. For instance, when we see a bowling ball go scooting down the lane and smashing into the pins, it certainly

seems

as though the ball has some kind of causal force in it. The ball is the cause, and the explosive reaction of the pins is the effect. Hume pointed out, though, that you can’t

see

causation in something but must only infer it from the constant relation between cause and effect. Every time the ball rolls into the pins, they bounce away. Ergo, the ball caused the pins to move. But there is no property of causality nestled somewhere in that ball, or hanging some-where in space between the ball and pins, that somehow works this magic. Causation is an event, not a thing or a characteristic or attribute of an object.

In the same sense, causation can’t be a property of a person’s conscious intention. You can’t

see

your conscious intention causing an action but can only infer this from the constant relation between intention and action. Normally, when you intend things, they happen. Hume remarked in

A Treatise on Human Nature

(1739) that the “constant union” and “inference of the mind” that establish causality in physical events must also give rise to causality in “actions of the mind.” He said, “Some have asserted . . . that we feel an energy, or power, in our own mind. . . . But to convince us how fallacious this reasoning is, we need only consider . . . that the will being here consider’d as a cause, has no more a discoverable connexion with its effects, than any material cause has with its proper effect. . . . In short, the actions of the mind are, in this respect, the same with those of matter. We perceive only their constant conjunction; nor can we ever reason beyond it. No internal impression has an apparent energy, more than external objects have” (400-401). Hume realized, then, that calling the will a force in a person’s consciousness—even in one’s own consciousness—must always overreach what we can see (or even introspect) and so should be understood as an attribution or inference.