The Illusion of Conscious Will (9 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

Overall, these studies of muscle effort and of phantom limbs suggest that the experience of conscious will is not anatomically simple. There does not seem to be “will wiring” spilling from the connections between brain and body, and one begins to wonder whether the muscles are even a necessary part of the system. In a sense, it is not clear that

any

studies of the sense of effort in movement can isolate the anatomical source of the experience of conscious will. Although the hope of isolating the experience of will is certainly one of the motivations of the researchers studying muscle sense and phantom limbs, a key case of willed action is left out in this approach—the action of the mind (Feinberg 1978). We all do things consciously with our minds, even when our bodies seem perfectly still. William James (1890, 452) described the “voluntary acts of attention” that go into willful thought, and this effort of attending seems quite as palpable as the effort that goes into muscle movement.

Ask a fifth grader, for example, just how much effort she put into a long division problem despite very little muscle movement except for pencil pushing and the occasional exasperated sigh. She will describe the effort at great length, suggesting that there is something going on in her head that feels very much like work. All the effort that people put into reasoning and thinking does not arise merely because they are getting tired scratching their heads. The question of whether there is a sense of effort at the outset, as the mental act starts, or only later, when the mental act has returned some sort of mental sensation of its occurrence, be-gins to sound silly when all the components of this process are in the head. Rather, there is an experienced feeling of doing, a distinct sense of trying to do, but this doesn’t seem to have a handy source we can identify. Certainly, it doesn’t seem to be muscle sense.

5

But it also doesn’t seem to be a perception of a brain signal going out to some other part of the brain. The experience of consciously willing an action may draw in some ways upon the feeling of effort in the muscles, but it seems to be a more encompassing feeling, one that arises from a variety of sources of sensation in the body and information in the mind.

5

. Someoneperseveringonthemuscleexplanationherecouldreplythat thoughts can involve unconscious movement of the vocal muscles, which in fact is sometimes true (Sokolov 1972; Zivin 1979). However, then it would also have to be suggested that muscles move for all conscious thoughts, and this has not been established (but see Cohen 1986).

Brain Stimulation

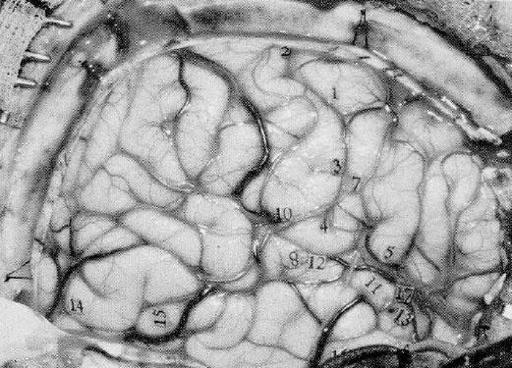

The most direct anatomical approach to locating conscious will involves poking around in the living human brain. This approach is not for the squeamish, and nobody I know would be particularly interested in signing up to be a subject in such a study. So there is not much research to report in this area. The primary source of evidence so far is research con-ducted in the 1940s and 1950s—the famous “open head” studies by the neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield. Penfield mapped a variety of sensory and motor structures on the brain’s surface by electrically stimulating the cortical motor area of patients during brain surgery. The surgery was con-ducted under local anesthetic while the patient was conscious (

fig. 2.5

), and this allowed Penfield to ask what happened when, for example, the stimulation caused a person’s hand to move. In one such case, the patient said, “I didn’t do that. You did.” (Penfield 1975, 76). When further stimulation caused the patient to vocalize, he said: “I didn’t make that sound. You pulled it out of me.” Penfield (1975, 77) observed of the patient that “If the electrode moves his right hand, he does not say ‘I wanted to move it.’ He may, however, reach over with the left hand [of his own accord] and oppose the action.”

Now, the movements the patient was making here were not the spasms one might associate with electrical stimulation of a muscle itself. These were not, for example, like the involuntary ear jerks that Bair (1901) prompted in his subjects when he electrified a muscle to get them to wiggle an ear. Instead, the movements Penfield stimulated in the brain were smooth movements involving coordinated sequences of the operation of multiple muscles, which looked to have the character of voluntary actions, at least from the outside (Penfield and Welch 1951; Porter and Lemon 1993). They just didn’t feel consciously willed to the patient who did them. In this case, then, the stimulation appears not to have yielded any experience of conscious will and instead merely prompted the occurrence of voluntary-appearing actions.

Figure 2.5

Penfield’s (1975) photo of the exposed conscious brain of patient M. The numbers were added by Penfield to indicate points of stimulation, and do not indicate the discovery of the math area of the brain. Courtesy Princeton University Press.

Penfield’s remarkable set of observations are strikingly in counterpoint, though, with those of another brain stimulation researcher, José Delgado (1969). Delgado’s techniques also stimulated the brain to produce movement, but in this case movement that was accompanied by a feeling of doing. Delgado (1969) reported,

In one of our patients, electrical stimulation of the rostral part of the internal capsule produced head turning and slow displacement of the body to either side with a well-oriented and apparently normal sequence, as if the patient were looking for something. This stimulation was repeated six times on two different days with comparable results. The interesting fact was that the patient considered the evoked activity spontaneous and always offered a reasonable explanation for it. When asked “What are you doing?” the answers were, “I am looking for my slippers,” “I heard a noise,” “I am restless,” and “I was looking under the bed.” (115-116)

This observation suggests, at first glance, that there is indeed a part of the brain that yields consciously willed action when it is electrically stimulated. However, the patient’s quick inventions of purposes sound suspiciously like confabulations, convenient stories made up to fit the moment. The development of an experience of will may even have arisen in this case from the stimulation of a whole action-producing scenario in the person’s experience. In Delgado’s words, “In this case it was difficult to ascertain whether the stimulation had evoked a movement which the patient tried to justify, or if an hallucination had been elicited which subsequently induced the patient to move and to explore the surroundings” (1969, 116). These complications make it impossible to point to the “feeling of doing” area of the brain, at least for now. And given the rare conditions that allow neurosurgeons ethically to tinker with brain stimulation at all, it is not clear that this particular approach is going to un-cover the precise architecture of the brain areas that allow the experience of conscious will.

No matter where such an area might be, though, the comparison of Delgado’s patient with the one examined by Penfield suggests that the brain structure that provides the experience of will is

separate

from the brain source of action. It appears possible to produce voluntary action through brain stimulation with or without an experience of conscious will. This, in turn, suggests the interesting possibility that conscious will is an add-on, an experience that has its own origins and consequences. The experience of will may not be very firmly connected to the processes that produce action, in that whatever creates the experience of will may function in a way that is only loosely coupled with the mechanisms that yield action itself.

This point is nicely made in another brain stimulation experiment, one that was carried out without any surgery at all. For this study, BrasilNeto et al. (1992) simply used magnets on people’s heads. They exposed participants to transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor area of the brain (

fig. 2.6

). High levels of magnetic stimulation have been found to influence brain function very briefly and can have effects somewhat like that of a temporary small lesion to the area of the brain that is stimulated. (Kids, don’t play with this at home.)

In this experiment, a stimulation magnet was poised above the participant’s head and aimed in random alternation at the motor area on either side of the brain. Then the participant was asked to move a finger when-ever a click was heard (the click of the electrical switch setting off the magnet). Participants were asked to choose freely whether to move their right or left index finger on each trial. Then the magnet was moved around while they responded. Although the stimulation led participants to have a marked preference to move the finger contralateral to the site stimulated, particularly at short response times, they continued to perceive that they were voluntarily choosing which finger to move. When asked whether they had voluntarily chosen which finger to move, participants showed no inkling that something other than their will was creating their choice. This study did not include a detailed report of how the experience of voluntariness was assessed, but it is suggestive that the experience of will can arise independently of actual causal forces influencing behavior.

Figure 2.6

Transcranial magnetic stimulation, as in the experiment by Brasil-Neto et al. (1992). Actually, the modern TMS device looks like a doughnut on a stick and can be waved around the head easily. The contraption in this photo is a magnet used by Silvanus P. Thompson trying to stimulate his brain electromagnetically in 1910. This impressive machine gave him some spots in front of his eyes but little else.

As an aside on these brain stimulation studies, we should recognize that it is not even clear that the sense of conscious will must be in any one place in the brain. Such general functions of consciousness may be at many locations in the brain, riding piggyback on other functions or being added to them at many different anatomical sites (Dennett and Kinsbourne 1992; Kinsbourne 1997). Studies of the influence of brain damage on awareness indicate that even minute differences in the location of damage can influence dramatically the degree to which a patient is aware of having a particular deficit (Milner and Rugg 1992; Prigatano and Schacter 1991; Weiskrantz 1997). There may be parts of the brain that carry “aware” signals and other parts that simply carry signals. The motor functions that create action and the structures that support the experience of conscious will could be deeply intertwined in this network and yet could be highly distinct.

The research to date on the anatomy of conscious will, taken as a whole, suggests that there are multiple sources of this feeling. It appears that a person can derive the feeling of doing from conscious thoughts about what will be done, from feedback from muscles that have carried out the action, and even from visual perception of the action in the absence of such thoughts or feedback. The research on phantom limbs in particular suggests that experience of conscious will arises from a remarkably flexible array of such indicators and can be misled by one when others are unreliable. The brain, in turn, shows evidence that the motor structures underlying action are distinct from the structures that allow the experience of will. The experience of will may be manufactured by the interconnected operation of multiple brain systems, and these do not seem to be the same as the systems that yield action.

When There’s a Will

Having explored how conscious will might be localized in space (in the human body and brain), we now turn to considering the dimension of time. Exactly when does conscious will appear in the events surrounding action? Questions of “when” address the mechanism of mind in a different way than questions of “where” because they focus attention on the sequential arrangement of the cogs in the machinery that cranks out our actions. This, in turn, informs us of the structure of the machine in ways that simply looking at its unmoving parts may not.

Lifting a Finger