The Illusion of Conscious Will (18 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

This chapter applies the theory of apparent mental causation to automatisms. We begin by exploring the classic automatisms—actions that under certain circumstances yield such curious and jarring absence of the feeling of doing that they have been celebrated for many years. To add to the earlier discussion of table turning, we look at automatic writing, Ouija board spelling, the Chevreul pendulum, dowsing, and the phenomenon of ideomotor action. The chapter then examines the key features of behavior settings that promote the occurrence of automatisms, and so points to the ways in which the lack of perceptions of pri-ority, consistency, and exclusivity underlie lapses in the experience of conscious will.

The Classic Automatisms

A standard college library has few books on automatisms except for books of the nineteenth century. The amount of literature on automatisms generated then by the spiritualist fad in America and Europe is astounding. There are stacks on stacks of dusty books, each describing in detail spooky experiences at a séance of some family or group. People caught up in this movement took seriously the idea that when humans behave without conscious will, their behavior is instead caused by spirits of the dead. And this, of course, is great fun. With no television, an evening’s entertainment for the family in that era often involved yet another séance to attempt to communicate with dead Aunt Bessie, her cat, or a spirit who knew them.

The spiritualist movement attracted extraordinary popular attention and focused in the early years (1848-1860) on the automatisms—particularly table turning, tilting, and rapping—and on spirit mediumship, the ability to experience automatisms regularly and easily. According to a

Scientific American

article of that time, “A peculiar class of phenomena have manifested themselves within the last quarter century, which seem to indicate that the human body may become the medium for the transmission of force . . . in such a way that those through whom or from whom it emanates, are totally unconscious of any exercise of volition, or of any muscular movement, as acts of their own wills” (“What Is Planchette?” 1868, 17). Demonstrations of such unconscious actions piqued public interest, and the popularity of the automatisms helped to fuel the spiritualist fad (

fig. 4.1

).

Figure 4.1

French Victorian salon games included hat turning (at the table on the left), table turning (center), and pendulum divining (right). From

L’Illustration

(1853).

The genuine experience of automatism, unfortunately, was not the only phenomenon underlying the interest in spirits. There was also trickery. People were unusually ready to accept spurious evidence of spirits offered by charlatans, and several widely known cases, which only later were traced to trickery, became celebrated at the beginning of the movement. Brandon (1983) points in particular to the early influence of the “spirit rappings” heard by many people in the presence of two young girls, Katherine and Margaretta Fox, in the spring of 1848. Large crowds gathered to witness these phenomena, which were publicized via the popular press. Confessions by the girls, given much later, indicated that they were making the noises by cracking their toe joints against tables or other sound-conducting surfaces. But by then the movement was well underway.

The demand to satisfy popular appetites led mediums and their managers to resort to an ever-expanding range of trickery to produce evidence of spirits. Séance phenomena eventually grew to include disembodied voices, dancing trumpets, apparitions of limbs, faces, or bodies, levitation, rapping on walls or tables, chalk writing on sealed slates, materialization of ectoplasm, and so on (Grasset 1910; Jastrow 1935; Podmore 1902; Washington 1995). My personal favorite is the ectoplasm, a gooey substance that for some reason emerged from a spirit medium’s mouth on occasion (always in the dark, and usually later to disappear) and that was taken as a physical embodiment of the spirit world. Why would

this

particular odd thing happen, and not something else? Why not the sudden appearance of jars of mustard in everyone’s pockets? If you’re an otherworldly spirit, why limit yourself to the equivalent of silly putty? At any rate, it seems that simple parlor automatisms such as table turning couldn’t compete with all the dramatic stunts produced by chicanery, so the entire spiritualist movement slowly devolved into something of a circus sideshow. With the inevitable exposure of the deceptions underlying these theatrics, the movement died in the early part of the twentieth century. Aside from a few anachronisms (e.g., a group in the 1960s that met to conjure up a table-rapping spirit called Philip; Owen 1976), the major course of spiritualism appears to be over.

This checkered past left many scientists suspicious of the genuineness of automatisms in general, and whatever valid observations were made in that era have largely languished as curiosities rather than serving to spur scientific inquiry. Any new approach to the automatisms therefore must retain a large measure of scientific skepticism. To that end, the phenomena discussed here have been reduced to a specified relevant few. Reports of events that sound so exaggeratedly supernatural as to suggest deception are not addressed. The focus on classic automatisms here is limited to motor movements that are accompanied by accounts indicating that the movement occurs without the feeling of doing, and that have been reported by enough different people so that the effect appears replicable. Even with these limitations, we are still left with a number of fascinating phenomena.

Automatic Writing

Consider, for example, the case of automatic writing. It is not clear who discovered it or when, but reports of automatic writing appeared often in the spiritualist literature.

1

Mattison (1855, 63) quotes one such individual: “My hand was frequently used, by some power and intelligence entirely foreign to my own, to write upon subjects of which I was uninformed, and in which I felt little or no interest.” Another said: “I found my pen moved from some power beyond my own, either physical or mental, and [believed] it to be the spirits.” James (1889, 556) quotes yet another: “The writing is in my own hand, but the dictation is not of my own mind and will, but that of another . . . and I, myself, consciously criticize the thought, fact, and mode of expressing it, etc., while the hand is recording the subject-matter.”

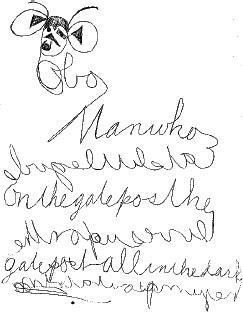

Some automatic writers claim to remain unaware of what their hands are writing, only grasping what has been written when they later read it. Others have ideas of what they are writing but report little sense that they are authoring the writing because the ideas “surge apparently from nowhere without logical associative relation into the mind” (Prince 1907, 73). The “automatic” part of automatic writing thus has two definitions, depending on which automatic writer we ask. The experience for some is a lack of consciousness of the written content, whereas for others it is more along the line of a lack of the experience of will even when there is consciousness of what is written. Unfortunately, both kinds of automatic writing seem perfectly easy to fake, so we depend on the good faith of the people who report the effect. An example appears in

figure 4.2.

The process itself usually involves writing while intentionally attending elsewhere. Automatic writing can be accomplished with pen and paper but is also sometimes performed with devices designed to enhance the effect—a sling supporting the arm above the writing surface (Muhl 1930) or, more commonly, a planchette (

figure 4.3

). This device, recognizable also in the design of the Ouija board pointer, is a heart-shaped or triangular piece of board mounted on three supports, often two casters and a pencil (Sargent 1869; “What Is Planchette?” 1868).

1.

Hilgard (1986), Koutstaal (1992), and Spitz (1997) give useful reviews of the historical and modern study of automatic writing.

Figure 4.2

The Oboman who scared little girls. A particularly fanciful example of automatic writing, featuring both an introductory doodle and reversing flow. From Mühl (1930). Courtesy Steinkopff Verlag.

Figure 4.3

An automatic writer with planchette and (optional) blindfold. Courtesy of Harry Price Library, University of London.

The use of special devices to reduce friction highlights an interesting feature of many automatic writings: Writers may well feel that they consciously intend to move but not that they consciously intend to move in a particular meaningful pattern. Solomons and Stein (1896) and Stein (1898) report getting started by making loops or other rhythmic motions in hopes that eventually this start would develop into writing.

2

Automatic writing, then, is not a movement that arises from a dead stop without any conscious initiation; the specifics of the movement just are either not consciously anticipated or are not sensed as voluntary.

With or without slings or planchettes, automatic writing gained great popularity as a pastime, and some people claimed that they wrote whole books this way. One spiritualist leader, the Rev. W. Stainton Moses, for instance, introduced his

Spirit Teachings

(in 1883, under the pseudonym M. A. Oxon) as having been “received by the process known as automatic or passive writing” (2). It is tempting on first hearing about automatic writing to run out and try it. I’ve given it my best shot, and nothing happened. Most people fail, like me; only about one in twenty will produce the full-blown phenomenon: sensible messages written without the experience of conscious will (Harriman 1942). This limit suggests that there may be something special about those who are susceptible to the effect, and indeed most of the early commentators on automatic writing sought out just such special, unusually florid cases for their studies. A regular Who’s Who of early psychologists—Binet (1896), James (1889), Janet (1889), and Prince (1890)—each published reports of automatic writing virtuosos.

One whimsical example of such an extreme should suffice. A gentleman, William L. Smith, who had amused himself with occasional planchette writing over a period of some two years, was observed by William James on January 24, 1889. Smith’s right hand was placed on a planchette while he sat with his face averted and buried in the hollow of his left arm. The planchette made illegible scrawling, and after ten minutes, James pricked the back of the right hand with a pin but got no indication of feeling from Smith. Two pricks to the left hand prompted withdrawal and the question “What did you do that for?” to which James replied, “To find whether you were going to sleep.” The first legible words from the planchette after this were

You hurt me

. A pencil was then substituted for the planchette, and now the first legible words were

No use in trying to spel when you hurt me so

. Later on, testing the anesthesia of the hand again, James pricked the right wrist and fingers with no sign of reaction from Smith. However, after an interval the pencil wrote,

Don’t you prick me any more

. When this last sentence was read aloud to him, Smith laughed and, apparently having been conscious only of the pricks on his left hand, said “It’s working those two pin-pricks for all they are worth.”