The Illusion of Conscious Will (21 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

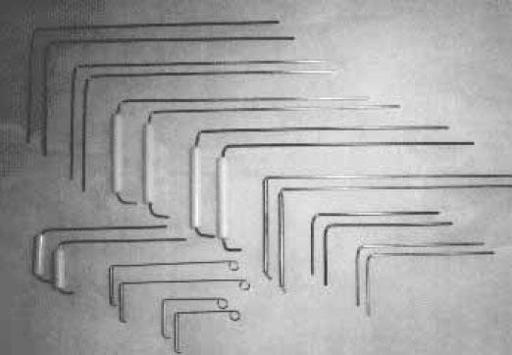

Figure 4.9

A selection of brass, chrome, and steel L-rods, available from the American Society of Dowsers.

Like the dowsing rod, the L-rod seems to operate on the principle of movement confusion, in that variations in the upright posture of the tube in the dowser’s hand translate into rotary movements of the wire perpendicular to the tube. As in the case of pendulum movement, the relation between what is thought about before the action and what happens becomes difficult to grasp intuitively or quickly, and the result is that the movements of the pointer often seem to the dowser to be unrelated to conscious thoughts and intentions. Ultimately, though, the movements of L-rods and Y-rods may follow from the same kinds of processes that lead beginning drivers inadvertently to steer in the direction they are looking (“Keep your eyes on the road!”). Unconscious sources of movement can be particularly powerful when one is unskilled in tracking the relation between one’s thought and action.

The apparent involuntariness of the rod’s movement seems to mask the role of the person’s thoughts in causing the movement. In a class of mine, for instance, a student performed a dowsing demonstration by placing a shot glass of water under one of five overturned opaque plastic cups while an experimental subject was outside the room. When the subject returned, she was given a small Y-rod and asked to find the water by dowsing for it. She picked the wrong cup, and said that the rod didn’t seem to move much. Then, after she was aware of where the water had been hidden, almost as an afterthought she was asked to try dowsing again. This time, the rod rapidly dipped over the correct cup, and the experimental dowser remarked that the rod really did seem to move of its own accord. The knowledge of the water’s location clearly informed her movement but was not interpreted as an intention that caused her movement. She reported feeling instead that the rod had moved.

As in the other automatisms, the experience of the involuntary dowsing movement often leads to an attribution of agency outside the self. Early dowsers ascribed their movements variously to water spirits, supernatural earth forces, and other gods of moisture, whereas more contemporary dowsers have added the possibilities of electrical fields, magnetism, and more scientific-seeming forces (e.g., Maby and Franklin 1939). The possibility that dowsing taps the dowser’s own unconscious ideas has also been suggested, and dowsing devices have been used as mind-reading devices, both by supposed mind readers and by people seeking self-knowledge of their own unconsciously held proclivities. Pendulums and L-rods can answer questions like those posed to the Ouija board. Much of the amazement at the responses occurs because the answers appear to be involuntary as the result of circumstances that reduce the perception of apparent mental causation.

Ideomotor Action

The clamor of interest in the spirits in the nineteenth century did not escape the attention of scientific psychologists. William Carpenter (1888) was intrigued by automatisms and yet was highly skeptical of the spiritualist interpretation of such things that was so popular in his time. As a response to the spiritualist agenda, he proposed a general theory of automatisms that still remains useful and convincing. According to his ideomotor action theory, “The Idea of the

thing to be done

. . . may, indeed, be so decided and forcible, when once fully adopted, as of itself to produce a degree of Nervous tension that serves to call forth respondent Muscular movements” (424). With one sweep, Carpenter proposed a central mechanism underlying table turning, pendulum movement, dowsing, automatic writing, and talking board spelling. In essence, he said the idea of an action can make us perform the action, without any special influence of the will. This ideomotor action theory depended on the possibility that ideas of action could cause action but that this causal relation might not surface in the individual’s experience of will. Thoughts of action that precede action could prompt the action without being intentions.

Now, the first question that arises is, Why do all thoughts of actions not yield immediate action? Why, when I think of walking like a duck, don’t I just do it? And given that you are also now thinking about it, why are you also not waddling around? (Are you?) James (1890) proposed an important addendum for the ideomotor theory to solve this problem, that “

every representation of a movement awakens in some degree the actual movement which is its object; and awakens it in a maximum degree whenever it is not kept from so doing by an antagonistic representation present simultaneously to the mind

” (Vol. 2, 526). I don’t do the duck thing on thinking about it, in other words, because I’m also (fortunately) thinking about not doing it. In this theory, we normally do whatever we think of, and it is only by thinking not to do it that we successfully hold still. For ideomotor theory, the will becomes a counterforce, a holding back of the natural tendency for thought to yield action.

Absentmindedness tends to produce ideomotor movements. James (1890) proposed that when we are not thinking very intently about what we are doing, we don’t tend to develop “antagonistic representations.” He gives examples: “Whilst talking, I become conscious of a pin on the floor, or some dust on my sleeve. Without interrupting the conversation I brush away the dust or pick up the pin. I make no express resolve, but the mere perception of the object and the fleeting notion of the act seem of themselves to bring the latter about. Similarly, I sit at table after dinner and find myself from time to time taking nuts or raisins out of the dish and eating them. My dinner properly is over, and in the heat of the conversation I am hardly aware of what I do, but the perception of the fruit and the fleeting notion that I may eat it seem fatally to bring the act about. . . . In all this the determining condition of the unhesitating and resistless sequence of the act seems to be

the absence of any conflicting notion in the mind

” (Vol. 2, 522523). This theory explains why one may loll around in bed in the morning thinking of all kinds of acts yet still lie there like a lump. According to James, such lumpishness is caused by a balancing or conflicting notion in the mind that keeps these acts from happening: besides thinking of the acts, one is also thinking of staying in bed.

People who have experienced certain forms of damage to their frontal lobes seem to be highly susceptible to ideas of action in just this way. Patients with such damage may exhibit what Lhermitte (1983; 1986) has called “utilization behavior,” a tendency to perform actions using objects or props that are instigated (often inappropriately) by the mere presence of those objects or props. An examiner sits with the patient, for example, and at no time makes any suggestion or encouragement for the patient to act. Instead, the examiner touches the patient’s hands with a glass and carafe of water. Normal individuals in this situation typically sit there and do nothing, but the frontal-damage patients may grasp the glass and pour it full from the carafe. Touching the patient’s hand with pack of cigarettes and a lighter prompts lighting a cigarette, and a variety of other objects may prompt their associated actions. One patient given three pairs of eyeglasses donned them in sequence and ended up wearing all three. It is as though, in these individuals, the Jamesian “conflicting notion” does not arise to stop the action, and the idea of the act that is suggested by the object is enough to instigate the action.

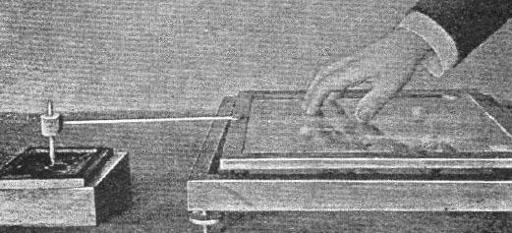

Experiments designed to overcome these “conflicting notions” in normal individuals have supported the ideomotor theory. One early laboratory demonstration was conducted by Jastrow and West (1892), for example, with the aid of a device they called an automatograph (

fig. 4.10

). This contraption consisted of a piece of plate glass resting in a wooden frame, topped by three brass balls, upon which rested another glass plate—kind of a super-planchette. The participant’s hand was placed on the upper plate, and recordings of movement were made with a pen attached to a rod extending from the plate while the participant tried to hold still. The investigators remarked that “it is almost impossible to keep the plate from all motion for more than a few seconds; the slightest movement of the hand slides the upper plate upon the balls” (399). A large screen inserted to prevent the participant from seeing the recording completed the apparatus. With such a sensitive surface, and an inability to tell just what one has done, there seems to be less possibility for a “conflicting notion” to arise and squelch automatic actions.

Figure 4.10

The automatograph. From Jastrow and West (1892).

The automatograph revealed a variety of interesting movement tendencies. Beyond all the drifting and wobbling one might expect from such movements, there were some remarkable regularities in how people moved in response to certain mental tasks. Asked to count the clicks of a metronome, for example, one person showed small hand movements to and fro in time with the rhythm. Another person was asked to think of a building to his left and slowly moved his hand in that direction. Yet another participant was asked to hide an object in the room (a knife) and then was asked to think about it. Over the course of some 30 seconds, his hand moved in the direction in which the knife was hidden.

It turned out that these movements followed not from thinking about a direction per se but more specifically from thinking about moving one’s hand in that direction. Further automatograph studies by Tucker (1897) revealed that the thought of movement itself was a helpful ingredient for the effect.

7

People who were thinking of movement showed directional movement effects more strongly than did people who were just thinking of a place. Tucker also found that a person who is intently watching a person or object move will sometimes show automatic hand movement. In

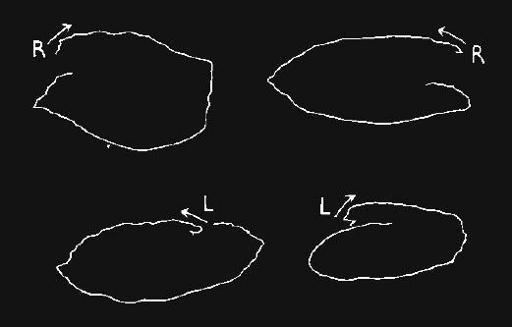

figure 4.11

, for example, we see an automatograph tracing for a person watching an object being moved around the room in closed curves. A tendency toward unconscious mimicry of movement may help translate the mere perception of movement into the thought of one’s own movement and thus into the occurrence of ideomotor automatism.

7.

In related studies, Arnold (1946) found that the more vividly a person imagined the movement, the more it occurred. So, for instance, standing still and imagining falling over—by thinking about both what it would look like and what it would feel like—produces more teetering than does thinking about either the look or the feel alone.

Figure 4.11

Automatograph tracing by a person watching an object being moved in circles around the room. From Tucker (1897).

Ideomotor action has also been observed with equipment designed to measure electrically what would otherwise be imperceptible muscle movements. These electromyograph (EMG) readings were first used for this purpose by Edmund Jacobson, the inventor of modern relaxation therapy techniques. While a male participant was relaxed in a darkened room, Jacobson (1932) asked him to imagine bending his right arm without actually bending it. An electrode on the right arm’s biceps-brachial muscles showed a deflection, an indication of electrical activity in the muscle. Asking the participant to think about bending his left arm or right foot created no such effect in the right arm, and requests to imagine the right arm perfectly relaxed or to imagine the right arm paralyzed also produced no indication of fine movement. Less direct suggestions to flex the arm, such as calling for the man to imagine himself rowing a boat, scratching his chin, or plucking a flower from a bush, however, again produced the indication of movement. All this served as a basis for Jacobson to propose that thinking about actions is what makes our muscles tense and that to relax we need to think about relaxing and not acting. These demonstrations suggest that thinking about acting can produce movement quite without the feeling of doing.