The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (22 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

David Ogilvy in Manhattan in 1954

© Bettmann/CORBIS

This idea of using different linguistic devices to target different audiences comes from the father of advertising, ad executive giant David Ogilvy, the 1948 founder of Ogilvy and Mather and inspiration for

Mad Men

. Ogilvy was a famous eccentric, coming to work in a billowing black cape or creating a scene at restaurants by

ordering a plate of ketchup as his entire meal

. As a twenty-five-year-old salesman in 1936, Ogilvy wrote a sales manual for the famous British stove, the Aga, that

Fortune

magazine called “probably the best sales manual ever written.” This excerpt from it explains his idea of customizing language:

There are certain universal rules. Dress quietly and shave well. Do not wear a bowler hat. . . . Perhaps the most important thing of all is to avoid standardisation in your sales talk. If you find yourself one fine day saying the same things to a bishop and a trapezist, you are done for.

Ogilvy had a lot of experiences with different (and tough) audiences; as a young chef in Paris he cooked for the president of France and met Escoffier but also remembered “the night our chef potagier

threw forty-seven raw eggs across the kitchen at my head

, scoring nine direct hits.” And he even specifically discusses when (and when not) to use two-dollar words. In his 1963 book

Confessions of an Advertising Man

he says,

“Don’t use highfalutin language”

when you’re talking to a non-highfalutin audience.

At the minimum, Ogilvy’s advice is to distinguish at least two audiences. The non-highfalutin audience is focused on family and tradition. The wealthier, middle or upper class audience is focused on education and health and striving to be unique and special, like Ogilvy himself, with his cape and his ketchup. Fitzgerald may or may not have been right that “the rich are different from you and me” but potato chip advertisers certainly think the rich

want

to be different from you and me, echoing food historian Erica J. Peters’s dictum that what people eat “reflects

not just who they are, but who they want to be.”

Politicians use metaphors linked to the desire for traditional authenticity and interdependence when appealing to country or working-class audiences, emphasizing traditional American foods, locales, and values. And they use linguistic devices associated with country too, with phrases like “strugglin’ ” and “rollin’ up our sleeves” that make use of the more country or

working-class

–in’

suffix

. The use of the

–ing

form associated with educated or upper-class speech, or the use of fancier words in general, and a focus on the language of health and nature, are an equally frequent political tactic for

appealing to more upscale voters

concerned about the local food supply, natural and nonartificial ingredients, and the health of our diet.

Whatever they might claim, politicians can’t really eat healthy, because they have to prove their authenticity by eating cheese steaks in Philadelphia or wings in Buffalo or donuts or hot dogs pretty much everywhere. Here in San Francisco that means the politicians eat

Chinese food at the Chinese New Year Parade, tamales at the Day of the Dead parade, and in a classic San Francisco mash up, dim sum before the Gay Pride parade.

But this ability to use different selves with different audiences is not just an ability of politicians, and these two ways of being are not just associated with differences in income. In their book

Clash!

cultural psychologists Hazel Rose Markus and Alana Conner show that these two audiences are related to two aspects of our personality, two ways of viewing the world that we make use of at different times and in different amounts.

What they call the

interdependent self

is our focus on our family, our traditions, and our relationships with people. The

independent self

is our focus on our need to be unique and independent. Each of us has an interdependent self and an independent self, sometimes focusing more on our need to be authentic, unique, and natural, and sometimes more on being rooted in relationships with our family, our culture, and our traditions.

In other words, like Warren Hellman, we are all fluid categories, combinations of these two models of our nation and our selves—models written on the back of every bag of potato chips.

Salad, Salsa, and the Flour of Chivalry

FLOUR AND SALT

ARE

an ancient combination, constituting, together with water, the minimal ingredients in bread from the most ancient times. San Franciscans have long baked using just these three ingredients, relying on our local fog-dwelling wild yeast and bacteria like

lactobacillus sanfranciscensis

instead of baker’s yeast. This “natural leavening” or

levain

tradition (and the famous “sourdough”), continues with modern local bakers like Steven Sullivan at Acme or Chad Robertson at Tartine. San Francisco artist Sarah Klein has even turned it into a performance piece; she sets up a mini kitchen in lobbies of high-rise office buildings downtown, starts mixing flour, water, salt, and starter, and random passersby join in the kneading and rising and slicing and eating of the hot sourdough.

In many cultures, salt is then added again. Bread and salt (

khubz wa-milh

) is an Arabic phrase that means the bond created by sharing food;

the Russian word for hospitality

is similarly

khleb-sol

(bread-salt), and bread and salt (and candles) is what my mom gave me, following Jewish tradition, when I moved to a new house.

But the link between flour and salt goes beyond their shared constituency in bread. These two ancient white powders are some of the earliest examples of processed, refined foods, dating back to the ancient human transition from hunter-gatherer societies to settled agriculture. This transition required finding new sources of salt, since

when humanity subsisted by hunting and gathering, we got enough salt from meat. This need led to an extensive industry of salt mining and seawater evaporation across the world, not to mention

thousands of years of salt taxes

. The transition to agriculture also meant the need to mill wheat into flour, a technology visible in Neolithic quern stones; the British Museum has

a grinding stone from Syria

that dates to 9500–9000

BCE

.

These days we spend a lot of time on efforts to rein in our unhealthy love of refined, salty foods. Potato chip advertisers, aware of the unhealthiness of the products, overcompensate by talking about how they are “healthier” and “low fat” with the “lowest sodium.” And online reviewers are equally aware, referring to “addicting wings” and “cupcakes like crack.” In this chapter we’ll examine the linguistic history of these ancient industrial foods to demonstrate that our craving for these salty, refined foods is old and unchanging—although they now come in more convenient snack-sized packages. We’ll start by looking at the linguistic history of flour, from the period when Anglo-Saxon was enriched with a vast French vocabulary brought by the Norman invasion.

Bread itself was so central to the medieval English diet that the word for the Anglo-Saxon ruler in his great mead hall was

hlaf-weard

(loaf-keeper), from his role in controlling the mills that ground grain into flour and distributing bread to his dependents. This word is perhaps more familiar in the modern form into which it evolved:

lord

. Our word

lady

similarly comes originally from the

Anglo-Saxon

hlaf-dige

(loaf-kneader)

.

After the 1066 invasion of the Normans, this association of food with the lordly class was maintained. The French spoken by this new ruling class began to be used instead of Anglo-Saxon for words that persist to modern-day English: pork, veal, mutton, beef, venison, bacon (from Old French

porc

,

veal

,

mouton

,

boeuf

, and so on). But while only the Norman lords could afford to regularly eat meat, it was

Anglo-Saxon-speaking serfs who raised the cows and pigs that the meat came from. Thus we use French

pork

for meat from the pig but still use old Anglo-Saxon words like

pig

(and

hog

and

sow

) for the animal itself. We still use Anglo-Saxon

cow

,

calf

, and

ox

, but refer to their meat with French

beef

and

veal

.

As part of this French invasion, sometime in the thirteenth century, a word spelled variously

flure

,

floure

,

flower

,

flour

, or

flowre

first appeared in English, borrowed from the French word

fleur

, meaning “the blossom of a plant,” and by extension, “the best, most desirable, or choicest part of something.” This second meaning occurs in the modern French word

fleur de sel

, which means the finest of the sea salts—delicate crystals harvested from the surface of evaporation pools.

The new English

flur

adopted both of the French meanings, pushing aside the old Anglo-Saxon word

blossom

, and coming to describe the best and choicest of all sorts of fancy high-class stuff. Thus we see phrases in Chaucer like “flower of chivalry” or “flower of knighthood” to describe the knights of the noble class.

Also in the thirteenth century, the phrase “flower of wheat” or “flower of meal” began to be used to describe the very finest, choicest part of wheat meal, made only of the white or endosperm of the wheat. A kernel of wheat has three parts: the endosperm, containing carbohydrates and protein; the fat and vitamin-rich “germ”; and the fibrous outer bran. Most bread in medieval times was made from the entire grain, sometimes with a portion of the bran removed. “Flower of wheat,” by contrast (or

flure of huete

as it might have been spelled at the time) meant the very fine white flour created by repeatedly sifting the wheat through a fine-meshed cloth. Each pass removed more of the bran or germ, leaving a finer and whiter flour. This process of sieving through cloth was called bolting and these

bolting cloths

were specially woven from canvas, wool, linen, and, much later, fine silk.

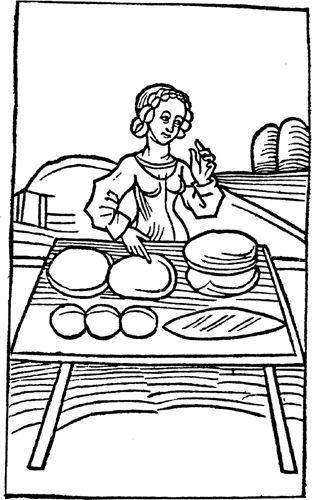

A medieval woman selling bread

The first breads made from these fine white flours were called

payndemayn

or

paindemain

, most likely derived from the Latin

panis dominicus

(lordly bread). The fine new payndemayn became a metaphor for whiteness as in Chaucer’s description of the handsome Sir Thopas in

The Canterbury Tales

:

“White was his face as payndemayn

, his lips red as a rose.”

Payndemayn is what is called for in the recipe I gave for “sops” and also in most early recipes for French toast. French toast was a common recipe in English cookbooks, first appearing around 1420 as

payn per-dew,

from the French

pain perdu

(lost bread), presumably after the staleness of the bread. (The name “French toast” doesn’t appear until the seventeenth century, and wasn’t common here in the United States until the nineteenth century.) Here’s one of the earliest French toast recipes, from a fifteenth-century manuscript. See if you can read the Middle English; most of the words, albeit differently spelled, are still part of modern English (like

frey hem a lytyll yn claryfyd buture

for “fry them a little in clarified butter” and

eyren drawyn thorow a streynour

for “eggs passed through a strainer”):

Take payndemayn or fresch bredd; pare awey the crustys. Cut hit in schyverys [slices]; fry hem a lytyll yn claryfyd buture. Have yolkes of eyren [eggs] drawyn thorow a streynour & ley the brede theryn that hit be al helyd [covered] with bature. Then fry in the same buture, & serve hit forth, & strew on hote sygure.

By the fourteenth century the English word

flower

(or

flour

) could mean any of these three things: a blossom, a finely ground wheat meal, or something which was the finest or best of something—both spellings were used to describe all of these until the modern spellings standardized around 1800. Shakespeare puns on these latter two meanings in

Coriolanus

, using “the flower of all” to mean the best of everything and “the bran” to mean whatever is left over: “All from me do back

receive the flower of all, and leave me but the bran.”