The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (23 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

In this Elizabethan era of Shakespeare, the rich ate a white bread successor of payndemayn called

manchet

, a fine white bread that could also be made with milk and eggs. Besides manchet and manchet rolls, finely bolted white flour was mainly eaten in cakes, cookies, and pastries. Even for the wealthy, however, white bread was reserved for special occasions.

Over the next few hundred years, white bread slowly became more and more favored. Partly this had to do with technology, as new silk bolting cloths imported from China in the eighteenth century made it possible and cheaper to make more finely bolted white flour. But mainly this had to do with the changing nature of tastes and the increasing desire for refined foods. By the mid-seventeenth century the Brown-Bakers guild specializing in dark loaves of rye, barley, or buckwheat merged with the White-Bakers guild and white bread and white flour came to dominate; social journalist Henry Mayhew reports that by 1800

brown bread was looked down upon even by the poor

.

These days we can use the word

flour

to mean any finely ground grain, whether it is whole wheat flour or even corn, spelt, rice, or barley flour. But the word still maintains something of its original usage; if you asked a neighbor to lend you a cup of flour, you probably wouldn’t be surprised if what you got handed was a cupful of fine, sifted, ground, white endosperm of wheat.

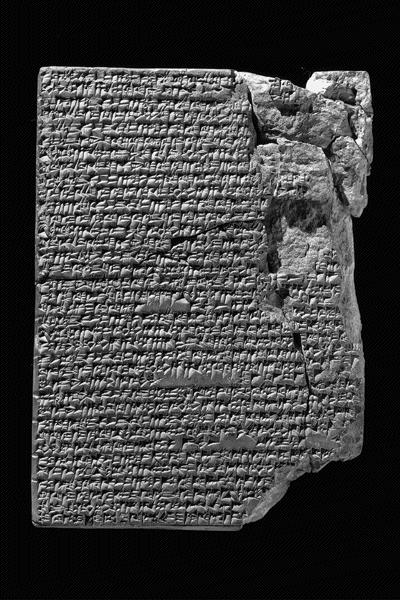

One of the Yale Culinary Tablets, in Akkadian from the Old Babylonian Period, ca. 1750

bc.

Yale Babylonian Collection.

English does have other quite different words for flour. An English word for flour with particularly ancient roots is our

semolina

, the coarsely ground grains of the endosperm of hard durum wheat. Semolina comes from Latin

simila

(fine flour) and Greek

semidalis

, both of which come from the Akkadian word

samidu

(high-quality meal)

. Akkadian was the language of ancient Assyria and Babylon, and samidu occurs in recipes in the world’s oldest known cookbook, the

Yale Culinary Tablets

. These were written in cuneiform around 1750

BCE

and also include recipes for what is probably the ancestor of the vinegar stew sikb j.

j.

Samidu’s

Latin descendant

simila

also gave rise to the English simnel cake, and to the Middle High German word

Semmel

, originally a roll made of fine wheat flour, a sense it still maintains in the

Yiddish word

zeml

. In modern German the word

Semmel

refers to the Austrian or Bavarian white Kaiser rolls or hard rolls, also favored in the United States in Wisconsin and other areas with German or Austrian roots. Next time you eat a bratwurst on a Sheboygan hard “semmel” roll remember that the name goes all the way back to the Assyrians.

Flour is also referenced in the name

sole meuni

è

re

, the classic French dish of fish fillets dredged in flour and pan-fried crisp in butter. A

meuni

è

re

is a miller’s wife, so a dish called “meunière” or

“à la meunière”

means one that is likely to be served in a miller’s house, hence containing flour.

What about that other white powder, salt? When we think of adding flavor to our food, we think of spices and herbs, peppers and ketchups and salad dressings and soy sauce, but the original food additive was salt. Salt’s importance in cuisine is visible in the vast number of foods in English with salt in their name.

Salad

and

sauce

(from French),

slaw

(from Dutch),

salsa

(from Spanish),

salami

and

salume

(from Italian) all come originally from the Latin word

sal

and originally meant exactly the same thing: “salted.”

The word

salad

, originally from Medieval Latin

salata,

came to English from Old French,

borrowed from Provençal

salada

. The very first written recipe for salad in English is in the first English cookbook, the 1390

Forme of Cury

. Despite the Middle English vocabulary it’s a pretty modern recipe, chock-full of greens and herbs (I’ve translated the ones that might be harder to figure out), dressed with oil, vinegar, garlic, and, naturally, salt:

Take persel, sawge [sage], grene garlic, chibolles [scallions], letys, leek, spinoches, borage, myntes, porrettes [more leeks], fenel, and toun cressis [town cress, i.e., garden cress], rew, rosemarye, purslarye; laue and waische hem clene. Pike hem. Pluk hem small with thyn honde, and myng [mix] hem wel with rawe oile; lay on vyneger and salt, and serue it forth.

The Provençal salada that became English salad itself developed out of the Late Latin

salata

, in the context

herba salata

(salted

vegetables). This medieval term was not used by the Romans of the classical period, although classical Romans definitely ate vegetables with a brine sauce. In fact Cato gives a recipe for a salted cabbage salad in his

De Agricultura

, from around 160

BCE

:

“If you eat it [cabbage] chopped

, washed, dried, and seasoned with salt and vinegar, nothing will be more wholesome.”

Much later, cabbages with salt and sometimes vinegar, often preserved longer, became prevalent in northern Europe, and later came to America. This is the origin of our

sauerkraut

, from the German “sour vegetable.” An even older American immigrant is the word

cole slaw

, from Dutch

kool

(cabbage) and

sla

(salad, from a Dutch shortening of the Dutch word

salade

). The Dutch had a huge influence on the development of New York (originally New Amsterdam), with a culinary legacy in American English that also includes the words

cookie

,

cruller

,

pancake

,

waffle

, and

brandy

. The first mention of what is probably cole slaw was in 1749, when Pehr Kalm, a visiting Swedish Finnish botanist, describes an “unusual salad” served to him in Albany by his Dutch landlady Mrs. Visher, made from thin strips of sliced cabbage mixed with vinegar, oil, salt, and pepper. Kalm says this dish

“has a very pleasing flavor and tastes better than one can imagine.”

This original

koolsla

gave way later to our modern mayonnaise-based dressing.

The word

sauce

in French and

salsa

in Spanish, Provençal, and Italian again come from popular Latin

salsus/salsa

, referring to the salty seasonings that made food delicious. Chaucer talks in 1360 of “poynaunt sauce,” by which he meant a sauce that was pungent or sharp, the old meaning of

poignant

. And various recipes for sauce, by now with or without salt, start appearing in cookbooks from the thirteenth century. (There are lots of sauces in the older cookbook known as

Apicius

, a fourth-century Latin collection of recipes

written by various authors, but the word used for sauce there is

ius,

the ancestor of our word

juice

.)

Many of my favorite sauces are called “green sauce,” like Mexican

salsa verde

of tomatillos, onions, garlic, serranos, and cilantro, or Italian

salsa

verde

, of parsley, olive oil, garlic, lemon or vinegar, and salt or anchovies. For Italian salsa verde Janet and I tend to add in whatever green herbs are growing in our gardens; here are the ingredients we tend to use:

Salsa Verde

1 cup Italian parsley leaves

¼

cup chives or wild garlic stems

leaves from 6 sprigs thyme

leaves from 2 sprigs tarragon

leaves from 2 sprigs rosemary

2 cloves garlic

¼

–

½

cup extra virgin olive oil

1 tablespoon lemon juice

2 anchovies

¼

teaspoon salt or to taste

Chop herbs with anchovies and garlic by hand, and then mix in oil, lemon juice, and salt.

I called it “Italian” salsa verde but from the twelfth to the fourteenth century green parsley sauces were made all across Europe. In Arabic salsa was called

sals

,

and scholar Charles Perry tells us

it was one of the few recipes that moved east from European Christians to the Muslim world rather than west from Muslims to Christians. A thirteenth-century cookbook from Damascus, the

Kitab al-Wusla

, told how to make “green sals” by pounding parsley leaves in a mortar with garlic, pepper, and vinegar.

French

saulce vert

was made of parsley

, bread crumbs, vinegar, and ginger in the fourteenth-century French cookbook

Le Viandier

, or made of parsley, rosemary, and sorrel or marjoram in

Le Menagier de Paris

.

There are other modern descendants of this sauce. In the twentieth century,

Escoffier’s French

sauce verte

called for pounding blanched parsley,

tarragon, chervil, spinach, and watercress and using the “thick juice” to flavor mayonnaise. This mayonnaise sauce verte was modified in 1923 at San Francisco’s Palace Hotel by adding sour cream and anchovies to create the recipe for

Green Goddess Dressing

, still served in the Garden Court at brunch.

The Palace Hotel has been around for almost 150 years; Sarah Bernhardt brought her pet baby tiger there, Enrico Caruso stayed there on the night of the ’06 earthquake, and the Maxfield Parrish painting of the Pied Piper in the bar is a San Francisco landmark. My high school prom was there, too, back when Donna Summer and Peaches and Herb were at the top of the charts. In the prom picture I just dug out to show Janet, I certainly rocked the bowtie, but unlike the original recipe for Green Goddess Dressing, below, our perfectly feathered hair did not stand the test of time.

Green Goddess Dressing

1 cup traditional mayonnaise

½

cup sour cream

¼

cup snipped fresh chives or minced scallions

¼

cup minced fresh parsley

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

1 tablespoon white wine vinegar

3 anchovy fillets, rinsed, patted dry, and minced

salt and freshly ground pepper to taste

Stir all the ingredients together in a small bowl until well blended. Taste and adjust the seasonings. Use immediately, or cover and refrigerate.

The earliest known recipe for one of the green sauces, however, seems to be an English recipe written mainly in Latin with some

Norman French and English

in a volume written over 800 years ago in 1190

by English scholar and scientist Alexander Neckam. The recipe was called

verde sause

and it called for parsley, sage, garlic, and pepper, and ends “non omittatur salis beneficium,” which translates roughly to “Don’t forget the salt.”