The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (32 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

Suppose I told you that in the Martian language one of these two was called bouba and the other was called kiki and you had to guess which was which. Think for a second. Which picture is bouba? Which kiki? How about maluma versus takete?

If you’re like most people, you called the jagged picture on the left

kiki

(or

takete

) and the round one on the right

bouba

(or

maluma

). This test was invented by German psychologist Wolfgang Köhler, one of the founders of Gestalt psychology, in 1929. Linguists and psychologists have repeated this experiment using all sorts of made-up words with sounds like bouba and kiki, and no matter what language they study, from Swedish to Swahili to a remote nomadic population of northern Namibia, and even in toddlers two and a half years old, the results are astonishingly consistent. There seems to be

something about jagged shapes

that makes people call them

kiki

and rounder curvy shapes that is somehow naturally

bouba

.

The link to food comes from the lab of Oxford psychologist Charles Spence, one of the world’s foremost researchers in sensory perception. In a number of recent papers, Spence and his colleagues have studied the link between the taste of different foods, the curved and jagged pictures, and words like

maluma/takete

.

In one paper, for example, Spence, Mary Kim Ngo, and Reeva Misra

asked people to eat a piece of chocolate and say whether the taste better matched the words

maluma

or

takete

. People eating milk chocolate (Lindt extra creamy 30 percent cocoa) said the taste fit the word

maluma

(and also matched the curvier figure). People eating dark chocolate (Lindt 70 percent and 90 percent cocoa) instead chose the word

takete

(and matched the jagged figure). In another paper they found similar results for carbonation; carbonated water was perceived as more “kiki” (and spiky) and still water was perceived as more “bouba” (and curvy). In other words, words with m and l sounds like

maluma

were associated with creamier or gentler tastes and words with t and k sounds like

takete

were associated with bitter or carbonated tastes.

These associations are very similar to what I also found with consonants in ice cream and cracker names. I found that l and m occurred more often in ice cream names, while t and d occurred more often in cracker names.

So what is it about bouba and maluma that people associate with visual images of round and curvy, or tastes of creamy and smooth, while kiki and takete are associated with jagged visual images and sharp, bitter, and sour tastes?

Recent work by a number of linguists

studied exactly which sounds seem to be causing the effects.

One reasonable proposal for what’s going on has to do with continuity and smoothness. Sounds like m, l, and r, called

continuants

because they are continuous and smooth acoustically (the sound is pretty consistent across its whole length), are more closely associated with smoother figures. By contrast,

strident

sounds that abruptly start and stop, like t and k, are associated with the spiky figures. The consonant t has the most distinct jagged burst of energy of any consonant in English.

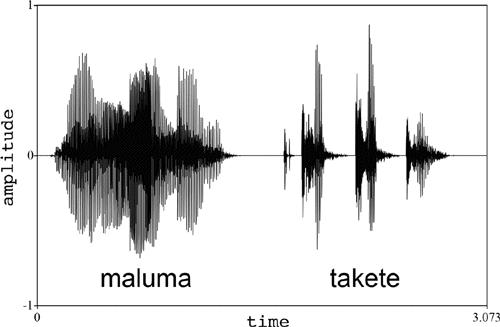

To help you visualize this, look at the display on the following page of the sound waves from a recording that I made of myself saying “maluma” followed by “takete.” Note the relatively smooth wave for maluma, which has a relatively smooth flow of air. By contrast, the three sharp discontinuities in takete on the right occurred when I said the sounds t and k; for each of these consonants, the airflow is briefly blocked by the tongue in the mouth, and then a little burst of air explodes out.

The waveform (sound waves) of me saying “maluma” and “takete”

What I call the synesthetic hypothesis suggests that the perception of acoustic smoothness by one of our five senses, hearing, is somehow linked to the perception of smoothness by two other senses: vision (seeing a curvy figure instead of a jagged one) and taste (tasting a creamy instead of sharp taste).

Synesthesia

is the general name for the phenomenon of strong associations between the different senses. Some people, like Dan Slobin, a Berkeley professor of psychology and linguistics, are very strong synesthetes. For Slobin, each musical key is associated with a color: C major is pink, C minor is dark red tinged with black. But the bouba/kiki results suggest that, to at least some extent, we are all a little bit synesthetic. Something about our senses of taste/smell, vision, and hearing are linked at least enough so that what is smooth in one is associated with being smooth in another, so that we feel the similarity between sharpness detected by smell (as in cheddar), sharpness detected by touch or vision (like acute angles), and sharpness detected by hearing (abrupt changes in sound).

We can see this link between the senses even in our daily vocabulary. The words

sharp

and

pungent

both originally meant something tactile and visual: something that feels pointy or subtends a small visual angle, but both words can be applied to tastes and smells as well.

It’s not clear to what extent these synesthetic links are innate or genetic, and to what extent they are cultural. For example,

nomadic tribes in Namibia

do associate takete with spiky pictures, but, unlike speakers of many other languages, they don’t associate either the word or the pictures with the bitterness of dark chocolate or with carbonation. This suggests that the fact that we perceive bitter chocolate as “sharper” than milk chocolate or carbonated water as “sharper” than flat water is a metaphor that we learn culturally to associate with these foods. But we really don’t know yet, because we are just at the beginning of understanding these aspects of perception.

There are, however, some evolutionary implications of the synesthetic smoothness hypothesis and of the frequency code.

John Ohala suggests that the link of high pitch with deference or friendliness may explain the origin of the smile, which is similarly associated with appeasing or friendly behavior. The way we make a smile is by retracting the corners of the mouth. Animals like monkeys also retract the corners of their mouths to express submission, and use the opposite facial expression (Ohala calls it the “o-face”), in which the corners of the mouth are drawn forward with the lips possibly protruding, to indicate aggression.

Retracting the corners of the mouth shrinks the size of the front cavity in the mouth, just like the vowels I or i. In fact, the similarity in mouth position between smiling and the vowel i explains why we say “cheese” when we take pictures; i is the smiling vowel.

Ohala’s theory is thus that smiling was originally an appeasement gesture, meaning something like “don’t hurt little old me.” It evolved when mammals were in competitive situations as a way to make the voice sound more high pitched and the smiler appear smaller and less aggressive, and hence friendlier.

Both the frequency code and the synesthetic smoothness hypothesis may also be related to the origin of language. If some kinds of meaning are iconically related to sounds in the way that these hypotheses

suggest, it might have been a way for speakers to get across concepts to hearers early on in the evolution of language. The origins of language remain a deep mystery. We do, however, have some hypotheses, like the “bow-wow” theory of language evolution, the idea that language emerged at least partly by copying nature, naming dogs after their bark and cats after their meow and so on. The frequency code suggests that perhaps one of the earliest words created by some cavewoman had high pitched sounds that meant “baby,” or low pitched α sounds that meant “big,” or perhaps was an acoustically abrupt

sounds that meant “baby,” or low pitched α sounds that meant “big,” or perhaps was an acoustically abrupt

kikiki

meaning “sharp.” Such iconic concepts are only a small part of the vast number of things we talk about using language, but iconicity still may help us understand some of these crucial early bootstrappings of human language.

Whatever their early origins, vowels and consonants have become part of a rich and beautiful system for expressing complex meanings by combining sounds into words, just as smiling has evolved into a means of expressing many shades of happiness, love, and much else.

Whatever hidden meanings words and smiles may have, in the end there is always ice cream, as a much later bard, Wallace Stevens, told us:

Let be be finale of seem.

The only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream.

Why the Chinese Don’t Have Dessert

IN TRENDY SAN

FRANCISCO

, the latest hip dessert is ice cream made with unusual flavors, like the banana-bacon ice cream served at Humphry Slocombe down on Twenty-Fourth Street. Bacon has been appearing on all sorts of desserts for some time now: bacon brownies, candied bacon, bacon peanut brittle. The donut shop down the street even has bacon-maple donuts. Now I’m sympathetic to the argument, made most persuasively by Janet, that bacon makes everything better. But I think that’s not the only reason for bacon’s dessert popularity: there’s something else going on that’s causing the hipster trend for all these bacon desserts. To solve the mystery, let’s begin by tracing dessert back to its early origins.

First of all, dessert doesn’t just mean “sweet food.” A donut on the way to the gym is not dessert; it’s just a lack of willpower. A dessert is a sweet course that’s part of a meal, and eaten at the end.

The placement at the end of the meal is expressed in the etymology: the word

dessert

comes from French, where it is the participle of

desservir

, “to de-serve,” that is, “to remove what has been served.” The word was

first used in France

in 1539 and meant what you ate after the meal had been cleared away; spiced wine called

hippocras

accompanied by fresh or dried fruit, crisp thin wafers, or candied spices or nuts called

comfits

or

dragées.

Such

dessert courses under various names

have a long medieval tradition, occurring in the very first menu we still have

for an

English feast, from around 1285

, where after “the table is taken away” the guests are served dragées and “plenty of wafers.” (

Dragée

is still the technical term for a confection with a hard candied shell like Jordan almonds or M&Ms.)

But the word

dragée

and the tradition of eating light sweets with wine after dinner dates back far earlier than the Middle Ages.

Dragée comes from the Greek word

tragemata

, which historian Andrew Dalby tells us was the name for the snacks eaten with wine in classical Greece after the table was cleared after a meal.

A “second table” was set

with wine and tragemata: cakes, fresh and dried fruits, nuts, sweets, and chickpeas and other beans.

Like comfits or dragées, their medieval descendants, however, tragemata were really snacks rather than what we now call dessert. In fact,

Herodotus remarked in the fifth century

BCE

in his

Histories

that the dessert-loving Persians mocked the Greeks for not really having any proper desserts at all:

[The Persians] have few solid dishes, but many served up after as dessert [“

epiphor

emata

”], and these not in a single course; and for this reason the Persians say that the Hellenes leave off dinner hungry, because after dinner they have nothing worth mentioning served up as dessert, whereas if any good dessert were served up they would not stop eating so soon.