The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (28 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

Macaroon, macaron, and macaroni remind us that the rare imported luxury of yesterday is the local popular culture of today—borrowed, maybe fluffed up a bit with egg whites or coconut to make it our own, a treat for each of us as we celebrate the coming of spring.

Sherbet, Fireworks, and Mint Juleps

THE SAN FRANCISCO

MIDSUMMER

fog was late in coming last year, which means Janet and I got a fantastic view of the Fourth of July fireworks from the top of Bernal Hill (both the municipal shows and the not-quite-so-legal ones that San Franciscans set off from rooftops throughout the city). Hot days are rare in our “cool gray city of love,” so random strangers were smiling at each other on Mission Street, the sidewalks were jammed with long lines in front of the ice creameries, and groups of people were picnicking in Dolores Park with icy cans of soda or cups of agua fresca or lemonade.

You may not be aware of the close relationships among these summer phenomena.

Ice cream was invented

by modifying a chemical process originally discovered for fireworks, and applying it to the fruit syrups that became lemonade, agua fresca, and sodas. And as we’ll discuss in the next chapter, the way ice cream flavors are named turns out to have a surprising relationship with the evolutionary origin of the human smile.

Ice cream has always been popular in San Francisco; Swensons, Double Rainbow, and It’s It were all founded here, and Rocky Road ice cream was invented across the bay in Oakland during the Great Depression. The latest inventions draw on the recent fads for molecular gastronomy and unusual flavor profiles. At Smitten in Hayes Valley they’ll make your ice cream fresh when you order it, freezing the slurry with liquid nitrogen. At Humphry Slocombe you can get foie gras, pink grapefruit tarragon, or strawberry black olive flavors. Bi-Rite

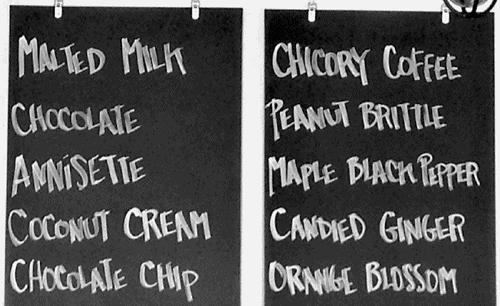

Creamery will happily sell you honey lavender, balsamic strawberry, and that modern classic, salted caramel. Mitchell’s specializes in Filipino and other tropical flavors like halo halo, lucuma, purple yam, and avocado. And Mr. and Mrs. Miscellaneous seems to keep running out of their latest hip flavor, orange blossom:

One day in the daily flavors

at Mr. and Mrs. Miscellaneous, the San Francisco ice creamery

Well, actually, orange blossom is not a newfangled flavor. Orange blossom is, in fact, the original ice cream flavor, appearing in the earliest recipes by the mid-1600s, the period when ice cream was invented. Ice cream was served in the Restoration court of Charles II as early as 1671, and food scholar Elizabeth David gives us what may be the English royal recipe,

handwritten in Grace Countess Granville’s Receipt Book

by the 1680s:

The Ice Creame

Take a fine pan Like a pudding pan ½ a ¼ of a yard deep, and the bredth of a Trencher; take your Creame & sweeton it w

th

Sugar and 3 spoonfulls of Orrange flower water, & fill yo

r

pan ¾ full . . .

By about 1696, a later edition of the cookbook attributed to La Varenne suggests using fresh orange flowers:

You must take sweet cream, and put thererto two handfuls of powdered sugar, and take petals of Orange Flowers and mince them small, and put them in your Cream, and if you have no fresh Orange Flowers you must take candied, with a drop of good Orange Flower water, and put all into a pot . . .

And

by 1700 other ice cream flavors

were developed as well, including pumpkin, chocolate, and lemon, and a plethora of early sorbets: sour cherry, cardamom, coriander-lemon, and strawberry.

Where did these flavors come from? And who first invented the freezing technology, the bath of salt and ice that these recipes share with modern homemade ice cream machines? The use of orange flower should give you a clue: the historical roots of ice cream and sorbet, like many of our modern foods, lie in the Muslim world.

The story begins with the fruit and flower syrups, pastes, and powders of the Arab and Persian world. In Cairo, for example,

medieval cookbooks give recipes for cooking quince

down into pastes with honey or sugar, flavored with vinegar and spices. Quince, a fruit that looks like a golden-yellow pear, has been renowned since classical Greece for its medicinal powers, which may account for its great acclaim. Quince paste spread from Cairo as far west as Muslim Andalusia, where it

appears in a thirteenth-century cookbook manuscript

. Its descendants are still popular today: in South America and Spain, where one is called

membrillo

(Spanish for “quince”) and in England and the United States, where we call another descendant “marmalade” (from Portuguese

marmelo

, “quince”).

Marmalade

meant “quince paste” in English until the start of the seventeenth

century, and somewhat longer in the United States. Early British recipes had the musk and rosewater of their Moorish Andalusian antecedents, but by the time the recipe made it into Amelia Simmons’s 1796

American Cookery

, the first American cookbook, the ingredients were just quince, sugar, and water:

To two pounds of quinces, put three quarters of a pound of sugar and a pint of springwater; then put them over the fire, and boil them till they are tender; then take them up and bruize them; then put them into the liquor, let it boil three quarters of an hour, and then put it into your pots or saucers.

To digress briefly, by about the same time in Britain, the Seville orange replaced the quince as the standard marmalade ingredient and orange marmalade became a breakfast staple, starting in Scotland. Here’s a Scottish recipe that food historian C. Anne Wilson gives from the 1760s:

Take the largest best Seville oranges, take the same weight of single refined sugar; grate your oranges, then cut them in two, and squeeze out the juice; throw away the pulp; cut down the skins as thin as possible, about half an inch long; put a pint of water to a pound of sugar; make it into a syrup . . . put in your rinds and gratings, and boil it till it is clear and tender; then put in your juice, and boil it till it is of a proper thickness . . .

More often than pastes, however, these medieval Arab sweet fruit concoctions were left in syrup form, where they were swallowed

medicinally or combined with water to form refreshing beverages. The Arabic word for these syrups was

shar

a

-

b

, from a root meaning “drink.” Here’s a syrup recipe from the medieval apothecary manual of a Jewish druggist in Cairo in 1260:

Opens liver obstruction and strengthens the liver. Take twenty dirhams of rhubarb, sprinkle over it three ratls of water for a day and a night and simmer over a low fire and thicken with three ratls of hard loaf sugar. Let it reach the consistency of syrups, remove and use.

When these Arab medical manuals were translated into Latin this word

sharab

became the medieval Latin word

siropus

, the ancestor of our English word

syrup.

In medieval Persia

, similar syrups were extracted from flowers like rose petals or orange blossoms, or fruits like sour cherry or pomegranate. These syrups were called

sharbat

, from another form of the same Arabic word, and sharbat was also the name of the refreshing drinks made by combining the syrups with water, cooled with snow and ice brought down from the mountains. When the Ottomans came, they enthusiastically adopted these sharbat, pronouncing them sherbet in Turkish.

The idea of bringing snow and ice from the mountains and storing them in icehouses to cool drinks in the summer is an ancient worldwide custom. The earliest recorded icehouses were pits lined with tamarisk branches 4000 years ago in Mesopotamia, but icehouses were common in ancient China and Rome and they are

even mentioned in the Bible

. Sharbats are still quite popular in Persia and Turkey and indeed throughout the eastern Mediterranean.

Claudia Roden talks nostalgically of the sharbat

of her childhood in Egypt, sharbat flavored with lemon, rose, violet, tamarind, mulberry, raisin, or liquorice. Here’s a modern Persian recipe from Najmieh Batmanglij:

6 cups sugar

2 cups water

1½ cups fresh lime juice

Garnish:

Springs of fresh mint

Lime slices

In a pot, bring the sugar and water to a boil. Pour in the lime juice and simmer over medium heat, stirring occasionally, for 15 minutes. Cool, pour into a clean, dry bottle, and cork tightly.

In a pitcher, mix 1 part syrup, 3 parts water, and 2 ice cubes per person. Stir with a spoon and serve well chilled. Garnish with sprigs of fresh mint and slices of lime.

By the sixteenth century French and Italian travelers had brought back words of these Turkish and Iranian sherbets. In one of the earliest mentions of the word in Europe,

the French naturalist Pierre Belon in 1553

described sherbets in Istanbul made of figs, plums, apricots, and raisins.

Thirsty passersby would buy a glass of syrup

from wandering sellers or stands, mixed with water and chilled with snow or ice to ward off the summer heat. Sherbets were most often sour. Lemons and sour cherries were some of the most popular flavors—and even vinegar was used.

In Turkey and Egypt, sherbet was often made from powders or tablets as well, as we see in this report from

Jean Chardin, a seventeenth-century French traveler

to Persia and the Ottoman Empire:

In Turky they keep them in Powder like Sugar: That of Alexandria, which is the most esteem’d throughout this large Empire, and which they transport from thence every where, is almost all in Powder. They keep it

in Pots and Boxes; and when they would use it, they put a Spoonful of it into a large glass of Water.

While erbet

erbet

in modern Turkey is mostly made from syrup now, old-style sherbet tablets, colored red and flavored with cloves, are still used to make a hot spiced sherbet called

lohusa erbet

erbet

served to new mothers

after the birth.