The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA (25 page)

Read The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA Online

Authors: John Ashdown-Hill

Barbara Ann Spooner was the third of the ten children of Isaac and Barbara Spooner, and she was born in 1777. She possessed a dark beauty, as we know both from her surviving portrait by Russell, and from contemporary descriptions of her. Those who knew her described her as pretty, pleasing and handsome. As to her character, we are told that she was a pious, sweet-tempered girl who had âconsiderable humility and a mind rather highly embellished than strongly cultivated'.

13

In the spring of 1797 the 20-year-old Barbara Spooner met a 37-year-old bachelor, the slave trade abolitionist William Wilberforce. Wilberforce, who until this point had appeared intent on remaining single (following a previous unsuccessful relationship) seems, during the winter of 1796/97 to have changed his mind. In Bath he confided his desire to find a partner to his friend Babington, who in response mentioned to him the name of Miss Spooner. Shortly thereafter, coincidentally as it seemed to Wilberforce (though in fact Babington may have given Barbara a hint), a letter reached Wilberforce asking for his advice in spiritual matters. The letter was from Barbara Spooner.

The entries in Wilberforce's private diary chart the progress of the affair from his point of view. For a while Wilberforce agonised over what he should do, but on the Sunday after Easter he wrote Barbara a proposal of marriage. âThat night I had a formal favourable answer.'

14

On the morning of Tuesday 30 May 1797 they were married, quietly, at the parish church of Walcot, Bath. Barbara had two bridesmaids, and after the ceremony they dined at her father's house. There was no honeymoon as such, and that night Barbara asked her new husband to join her in her prayers, following which they went to bed early. The following day the couple set off on a four-day tour of the schools in the Mendips run by Wilberforce's friend Hannah More. This somewhat unusual wedding journey seems to have passed off well enough, and Wilberforce confided his opinion, at the end of the trip, that âthere seems to be entire coincidence in our intimacy and interests and pursuits'.

15

Furneaux, one of William Wilberforce's modern biographers, has written that âit is difficult to be fair to Barbara'.

16

Unfortunately, Furneaux seems sometimes to be naively uncritical in his evaluation of his sources. The comments that he quotes from Wilberforce's wildly jealous friend, Marianne Thornton, for example, tell us at least as much about

her

as they do about Barbara! The

facts

which emerge from these hostile comments are that Barbara idolised her husband, and was unhappy when he was away from her. (A trait which William, at least, may have rather liked, since few human beings enjoy the feeling that their presence is readily expendable.)

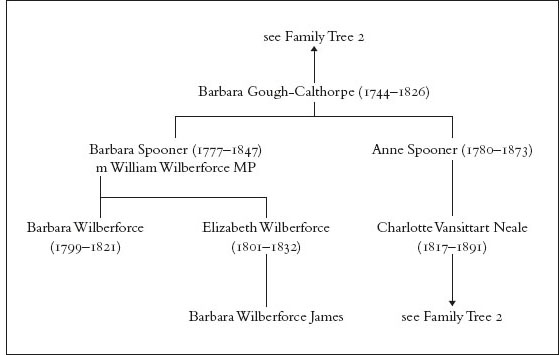

Probably Barbara was by nature an anxious person. As the years passed this tendency seems to have increased, and she worried a great deal about her children. However, the early deaths of her two daughters may help to make such anxieties more understandable. The Wilberforces had six children: four sons and two daughters, all of whom inherited from their mother the mitochondrial DNA of Richard III. The eldest son, another William, was born on 21 July 1798 (he lived until 1879) Robert (1802â57), Samuel (1805â73) and Henry (1807â73) followed. The two girls, Barbara (1799â1821) and Elizabeth (âLizzie' 1801â31) fit into the family tree between William and the three youngest sons. The elder daughter, Barbara Wilberforce, died unmarried and childless in her early 20s. Lizzie's life, though also short, lasted a little longer, and when she died she left a daughter of her own.

In January 1831 Lizzie married John James who, at the time, was an impoverished young curate. Her marriage proved short-lived. She quickly became pregnant, and bore her child towards the end of the year. Subsequently she fell ill with a chest infection, and although her husband brought her from their home in Yorkshire to stay on the Isle of Wight, where it was thought the climate would suit her better, in fact her condition continued to deteriorate. Early the following year Lizzie died. Sending Lord Carrington the sad news on 23 March 1832, her father wrote: âmy poor son-in-law and his little infant are indeed much to be pitied'.

17

The baptismal register of Rawmarsh, Yorkshire, where Rev. John James was curate, reveals that on 11 December 1831 his daughter by Lizzie Wilberforce was baptised Barbara Wilberforce James. No doubt her first name was chosen in honour of her grandmother and her deceased aunt. She grew up to marry Captain Charles Colquhoun Pye in 1860, at Avington, Berkshire, where her father John James had been the rector since the late 1830s. However, Barbara Wilberforce James left no heirs to carry forward the genetic heritage of Richard III and his family.

18

To follow the mitochondrial DNA of Richard III forward into the twentieth century we must now abandon the descendants of Barbara Spooner and William Wilberforce, and turn instead to the descendants of Barbara's younger sister, Anne Spooner.

Unlike her sister Barbara, Anne Spooner did not attract the jealous comments of other women. Her husband, an evangelical clergyman, the Rev. Edward Vansittart Neale, was never a well-known figure in the political and social world of his day, and no detailed portraits of the couple, either painted or verbal, have come down to us. Our one surviving glimpse of Anne seems to be a brief and anonymous mention of her by one of her granddaughters. It relates to a period near the end of Anne's life, when she was already more than 80 years old (for, like many members of the family which we are following, Anne Spooner was a long-lived lady). Born in 1780, in the reign of George III, she died at the age of 93, in 1873; the thirty-sixth year of Queen Victoria's reign.

F

AMILY

T

REE

6: The Wilberforce connection.

Anne, it seems, remained true to her chosen

métier

as the wife of an evangelical clergyman, and perhaps true also to her upbringing at her parents' home in Bath, which we have already heard described unflatteringly as âthe very temple of dullness'. Her granddaughter, Alice Strettell, then aged about 15, found herself sent home to England by her parents (who as we shall shortly see, were then living in Italy) in order that she might attend a boarding school in Brighton. She looked forward to her holidays, when she might return to the Continent and to her parents:

However, when the period of

congé

was short, or the weather seemed too bad for me to cross the channel, I was consigned to the care of a saintly but evangelically minded grandmother, and though her society was doubtless improving, such a holiday was, from my point of view, scarcely a relief from term-time. Many were the long Sundays I spent at the pretty satin sandalled feet of my grandmother as she sat by the green-verandahed window of her drawing room. In her cap of fluted tulle, tied under her chin with a ribbon, she taught me the Catechism and some terrifying hymns. Many, too, were the long, dull afternoons and evenings I spent sewing, or reading the Bible, until at nine o'clock the old butler appeared and my grandmother said, âBring in Prayers.'

19

Alice Strettell's pen portrait of Anne Spooner is brief but vivid. However, for Anne it is perhaps unfortunate that this record of her was preserved by a teen-aged granddaughter who was eager to be out in the fashionable world and living life to the full, and for whom the experience of life with the old lady felt, as Alice herself readily admits, as though âmy sprouting wings were clipped'.

Anne Spooner married a clergyman called Edward Vansittart Neale. The latter was born simply Edward Vansittart, and was not, in fact, of Neale descent. The family of Neale were seated in Staffordshire in the reign of Richard III. A descendant, John Neale, of Allesley Park, Warwick, died in 1793 without issue. At the death of his widow in 1805 the Allesley and other estates passed under her will to the Revd Edward Vansittart of Taplow, Bucks, with the provision that he should take the name and arms of Neale.

20

Joy Ibsen, a living descendant of Anne Spooner and Edward Vansittart Neale, recalled to me:

Edward's father owned Bisham Abbey in Berkshire, once a house of the Knights Templar and at one time owned by the Duke of Clarence and later his son, Edward [Earl of Warwick], who was beheaded in 1499 for attempting to escape from the Tower with âPerkin Warbeck'. In 1941 it belonged to Edward [Vansittart Neale]'s grand-daughter, Lady Vansittart Neale. There is supposed to be a curse on the place.

21

Anne Spooner's granddaughter, Alice Strettell (Comyns Carr) also remembered âthe home of my mother's family â the beautiful Gothic Abbey of Bisham near Marlow. We were staying with my cousin, George Vansittart, who was then the owner'.

22

The latter objected to trippers along the river Thames landing on his banks and used to chase them off.

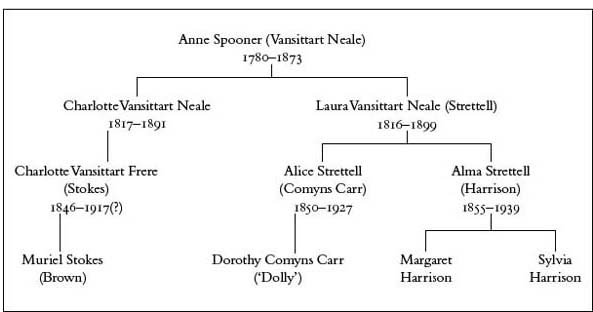

Anne Spooner and Edward Vansittart Neale produced a large family, in which daughters very much predominated â a fact which appears superficially promising for the future of the mitochondrial DNA of Richard III and his family. Unfortunately, several of the daughters remained unmarried. Alice Strettell, the granddaughter of Anne Spooner whom we have already met, was the elder daughter of one of Anne's daughters: Laura Vansittart Neale. Laura was born at Taplow (where her father held the living) in the year after the final defeat of Napoleon I at Waterloo. She died aged 62 in the year following Queen Victoria's golden jubilee.

Although Laura had clear views on what was and was not proper, and although, like her mother, she married a clergyman, her life was certainly not dull, and was open to unusually wide horizons. Her husband was Alfred Baker Strettell, who served for a time as her father's curate at Taplow, before accepting, in 1851, the rather unusual appointment as English chaplain at Genoa. The growing Strettell family (a son and two daughters) lived in Italy for many years â though in 1851, of course, no country called âItaly' yet existed. Indeed, the Strettells were to witness the process of Italian reunification at first hand, and in 1862, after the treaty of Villafranca, the family watched from the balcony of the British Consulate, as Garibaldi accompanied King Victor-Emanuel I and the Emperor Napoleon III of France in procession through the streets of Genoa.

23

Laura attended the royal ball at the palace later that evening and her elder daughter, Alice Laura Vansittart Strettell, has preserved for us a description of her mother's appearance on that occasion. Laura wore a crinoline with âspreading skirts of blue gauze garlanded with tiny rosebuds. Her hair was dressed low, in the prevailing fashion, with a pink rose fastened behind her ear and a long curl falling on her neck.'

24

Some hint of Laura's appearance may be glimpsed, perhaps, in a surviving photograph of her sister, Charlotte, which must have been taken at about this period, and which shows her wearing a spreading crinoline and a fine lace shawl. âThe photo of Charlotte Vansittart Neale as a young girl is interesting I think because of her lovely dress.'

25

The Italian upbringing of the Strettell children was unusual, and it produced unusual results in terms of the children's education. Both Alice and her sister had linguistic accomplishments. Alice spoke Italian like a native. Many years later she remembered her husband's delight, when he was trying to purchase something from an Italian vendor, âat the sudden drop of five francs in the demand of the astounded plunderer upon hearing his own vernacular from my indignant English lips'.

26

As Alice admitted later, however, she did not fully appreciate all the advantages of her upbringing at the time:

F

AMILY

T

REE

7: The Strettell connection.

There was much that must have been, unconsciously to myself, of rare educational advantage in the lovely scenery and picturesque surroundings of my childhood's life on the Riviera and in the Apennines; and my parents so loved both Nature and Art that they gave us contant change of opportunities in these directions. Yet I must confess that as I grew up, the chestnut groves of the Apennines and the shores of the blue Mediterranean became empty joys to me, ⦠and I longed for freedom and the attractions of the world â more especially in London, which I only knew through visits to relatives during the holidays of a short period of my life at a Brighton School. [So I] cajoled my father, then English chaplain at Genoa, into letting me âsee London' under the care of my brother, resident there.

27