The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (14 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

APRIL 12, 1945

BUCHENWALD CONCENTRATION CAMP

Near Weimar, Germany

M

ax Schmidt got to Weimar with G Company of the 317th Infantry Regiment, 80th Infantry Division, on April 12, a day after the city was taken. Max was an eighteen-year-old from Brooklyn who had shipped out of Boston just six weeks earlier. By the time he hit Weimar, it had been declared an open city. “In other words, there was no real fighting to liberate Weimar. The Germans surrendered. When you got close to it, you know there was something wrong because you could smell it in the air. In my opinion, that was the key, that’s why the Germans came to us, they came to our commanders and wanted to surrender, because they knew what we’d find, and that would be Buchenwald.”

Louis Blatz was another eighteen-year-old in the 80th, but he got lucky and arrived in Europe from the Detroit area just in time to serve as a rifleman at the tail end of the Battle of the Bulge. He was maybe five feet six and weighed 135 pounds, and he believed that he was invincible. “I never thought about dying. I’ve always had a feeling, all my life, even when I was a kid, you’re gonna die, there’s nothing you can do about it. Why worry about it and get sick?”

Blatz, like Schmidt, smelled Buchenwald long before he saw it. “We were walking along the road, our company, and all of a sudden somebody said, ‘Ooh! What’s that odor?’ And I said, ‘It smells like Mount Clemens.’ In the old days Mount Clemens, Michigan, was noted for mineral baths that smelled like rotten eggs, sulfur gas, an unpleasant odor. And farther along, we see the gates were wide open, we went in, and we see all these people standing there. And some of them had already been disrobed. Somebody had gotten there before us, and they were taking all their clothes away from them, spraying them down, washing them.

“Seeing it, you think, how could anybody be so inhumane as to treat people, fellow human beings, in that manner? All that ran through my mind was these people had no conscience; they didn’t care one way or another. They treated them as animals. It was just horrible. Because it was hard to breathe. The odor, the smell, the air. The crematoriums, some of them still had bodies burning in ‘em, so you could still smell it. And it was a relief on our part to get away from it, but you couldn’t forget, you couldn’t forget. After that, you just say to yourself, nobody better tell me that this didn’t happen.”

Eugene O’Neil was yet another eighteen-year-old who made it to Europe in time for the end of the Bulge. But the Marylander wasn’t as optimistic about his chances of surviving combat as Blatz was. He was sent from Le Havre by 40 and 8 railcar across France to a replacement depot in Belgium. “It was strange, and it was so cold, we even set the thing on fire trying to light a fire in the middle of the car to keep warm.” It was early January. He was trucked from the depot to C Company of the 1st Battalion, 319th Infantry Regiment. “When we got in, nobody said, ‘Hello, good-bye, go to hell,’ nothin’ else. Because the feeling, I think, was these guys are coming in to die. So nobody wanted to make any friends.” His first battle was at the Our River and then on the Siegfried Line, where he was pinned down for five or six days. “We couldn’t get out of the foxhole, and constant shelling, mortar fire, Screaming Meemies, rocket fire—it was enough to blow your mind. Some guys did lose their minds there.”

O’Neil’s unit stayed on the outskirts of Weimar. He doesn’t remember how he got to Buchenwald, but he recalls what he saw. “A lot of men who were nothing but skin and bones. The smell was real bad. I didn’t go into the camp.” He says there was so much horror—one thing after another, not just the camp but in war. Somehow, he just dealt with it all. “You gotta realize the difference between an infantryman and some of the other guys that came in afterwards and did the police work, did the cleanup. They were strictly the support troops like the MPs that come in along behind you. But when the infantry hits something, they get them out as quick as they can, particularly in a situation like that. I can picture those human beings there with nothing but flesh and bones, which was one of the most horrible sights that you could see. I didn’t know and didn’t understand the full horror of the camp until after the war was over.” Which may have been what helped him deal with it at the time.

Ventura De La Torre was just twenty years old when Cannon Company of the 317th Infantry Regiment, 80th Infantry Division, came to Buchenwald. He’d been drafted out of the citrus groves of Orange County, California, and gone to Europe with the division on the

Queen Mary

. He was a truck driver, towing a 105mm howitzer and hauling the shells for the gun. And he’d never heard of the mass killings or concentration camps until April 12, 1945.

“I couldn’t believe it. It was a terrible sight, feeling sorry for these people that couldn’t help themselves, nobody to help them. When we arrived, the people just walking toward us, like asking us, ‘Get us out of here.’ That was their feeling.

“Some just had a piece of blanket covering them. And their knees were nothing but skin and bone. Their ribs … a terrible sight to see them. When we went in, some of those guards, they had changed into inmates’ [uniforms]—but some of the people recognized them. I heard that [the prisoners] killed some of them. And then they had the ovens there. Oh, it was the smell—when I think about it, I can almost smell that.”

De La Torre was in the camp only three or four hours. His description of the dead—“stacked up like wood”—would be echoed by almost every American who set foot inside this camp and dozens of others. He remembers opening a door to one of the barracks. “Those people lined up shoulder to shoulder, and they were just staring at us. They were so weak; a lot of them couldn’t even get out. And there were dead with them in there, but I guess [the prisoners] just take them out and pile them up outside the barracks.”

Sixteen days after the 80th arrived at Buchenwald, the War Department Bureau of Public Relations issued a report on Buchenwald, first releasing it to war correspondents in Paris. The late Lieutenant Colonel Edward Temple Phinney, who had been with HQ VIII Corps in the final months of the war, tucked a copy of that report in his foot-locker. There it remained for more than sixty years until his great-nephew and the latter’s wife, Carl and Donna Phinney of Houston, Texas, discovered it and provided it to the author. The report puts into precise, often mathematical terms what the GIs were seeing and experiencing in the camp.

TEXT OF OFFICIAL REPORT OF BUCKENWALD [

sic

] ATROCITIES

The following text of the official report of the Prisoner of War and Displaced Persons Division, United States Group Control Council, has been forwarded from Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces to the War Department. It’s [

sic

] contents were made available to correspondents in Paris, April 28, 1945.

The text:

Inspection of German Concentration camp for political prisoners located at Buckenwald on the north edge of Weimar was made by Brigadier General Eric F. Wood and Lieutenant Colonel Charles K. Ott on the morning of April 16, 1945.

… 2. History of the camp: It was founded when the Nazi party first came into power in 1933, and has been in continuous operation ever since although its largest populations date from the beginning of the present war. U.S. armor overran the general area in which the camp is located on April 12. Its SS Guard had decamped by the evening of April 11. Some U.S. Administration personnel and supplies reached the camp on “Friday the 13th” of April—a red-letter day for the surviving inmates.

3. Surviving population: Numerically, by nationality, as of April 16, 1945:

| French | 2,900 |

| Polish | 3,800 |

| Hungarians | 1,240 |

| Jugoslavs | 570 |

| Russians | 4,380 |

| Dutch | 584 |

| Belgians | 622 |

| Austrians | 550 |

| Italians | 242 |

| Czechs | 2,105 |

| Germans | 1,800 |

| Anti-Franco Spanish and Misc | 1,207 |

| TOTAL | 20,000 |

(Four thousand of the total were Jews.)

… 5. Mission of the Camp: An extermination factory. Mere death was not bad enough for anti-Nazis. Means of extermination: Starvation; complicated by hard work, abuse, beatings and tortures, incredibly crowded sleeping conditions (see below), and sickness (for instance, typhus rampant in the camp; and many inmates tubercular). By these means many tens of thousands of the best leadership personnel of Europe (including German democrats and anti-Nazis) have been exterminated. For instance, 6 of the 8 French generals originally committed to the camp, and the son of one of them, had died there.

The recent death rate was about 200 a day. 5,700 had died or been killed in February; 5,900 in March; and about 2,000 in the first 10 days of April.

The main elements of the installation included the “Little Camp,” the “Regular Barracks,” “The Hospital,” the medical experimentation building, the body disposal plant, and an ammunition factory immediately adjacent to this camp and separated from it only by a wire fence.

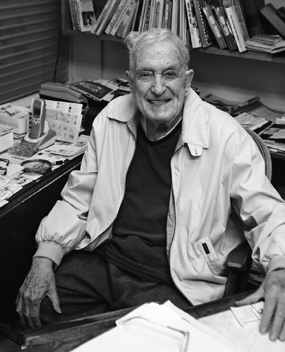

Melvin Rappaport first heard the words “concentration camp” in a Hollywood movie just before the war. He saw his first one—Buchenwald—on April 13, 1945, and recalls that “the stench was beyond your wildest dreams.” The Queens, New York, native stays in touch by e-mail with dozens of World War II veterans

.

In the week preceding the arrival of the Americans, the Nazis moved 23,000 prisoners out of Buchenwald, lest they fall into enemy hands. Two trains with 4,600 prisoners were sent to Theresienstadt, Czechoslovakia, 160 miles to the east. Another train, with 4,800 prisoners destined for Dachau, was liberated en route. Still another, with 4,500 prisoners bound for Dachau, made it only to Gera, forty-five miles east of Buchenwald, where it was liberated. A train with 1,500 prisoners was sent 170 miles east, to Leitmeritz, Czechoslovakia. And two trains were dispatched to the concentration camp at Flossenbürg, 120 miles to the south. One train, with 3,105 inmates, arrived there. The other, with 4,500 prisoners, was detoured through Czechoslovakia, taking its human cargo on a hellish three-week journey that ultimately ended at Dachau.

Captain Melvin Rappaport was part of a headquarters unit with the 6th Armored Division. He’d been going to the City College of New York when he opted to join the Army six months before Pearl Harbor. He volunteered for Officer Candidate School (OCS) and was commissioned a second lieutenant assigned as a platoon leader in the newly organized 6th Armored Division. He went overseas with the unit and became a liaison for air support, wandering the countryside in a half-track talking to the fighter planes overhead via UHF radio. He was at Bastogne, where he remembers losing about a third of the division in the bitter fighting. “Somehow we survived it. Youth, that was the thing,” he recalls in his Queens, New York, home. “When you’re twenty, twenty-one years old, you can take anything. We got through the Siegfried Line, etc., and then it was April.”

Mel knew a bit more than his buddies about Germans and Jews: he’d learned it from the movies. “There was a movie with James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan called

The Mortal Storm

, a 1940 film in which they played a couple in Germany. Her father was a professor and they were Jewish, so they threw them in a concentration camp. That was the first time I ever heard the words ‘concentration camp.’”