The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (16 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

The 84th arrived in Europe in October 1944, and Ayers is a bit understated in describing what it was like for a twenty-five-year-old to be leading men in combat for the first time. “Don’t overlook the word ‘scared,’” he says, “because I was.” The men in his platoon were from all over the United States and from all walks of life. Not surprisingly, he has a fairly forthright assessment of their fighting ability. “Let me say this: the ones that caused the most trouble in civilian life sometimes turned out to be the best soldiers. In other words—I won’t use this word literally—but a gangster on the streets of New York was a helluva soldier in the field.”

Despite the fact that he was his company’s executive officer as well as a platoon leader responsible for dozens of enlisted men, Ayers was given no advance warning that they might encounter concentration camps. His introduction to the subject was intense: “I literally saw the guards on the gate there in Salzwedel shot and killed. I personally didn’t fire a shot—I was behind.”

Salzwedel had begun operations with a thousand female slave laborers less than a year earlier, in mid-1944. This subcamp of Neuengamme existed to provide workers for a privately owned company whose primary mission was the production of explosives and bullets. The factory operated around the clock, with the women working under brutal SS supervision in twelve-hour shifts with one fifteen-minute meal break.

By the beginning of April 1945, Salzwedel was being used as a collecting point for transports of female prisoners from camps being evacuated to avoid the oncoming Russians. In its final days, there were more than 3,000 crowded into the camp, including a large contingent of Dutch women evacuated from Ravensbrück. The guards outside the barbed wire were generally Wehrmacht soldiers unfit to serve in combat units. On the inside, security was provided by approximately ten male SS members supervising an equal number of female guards, some of whom attempted to blow up the camp and its inmates as the American soldiers approached.

Lea Fuchs-Chayen was a teenager standing near the gates of Salzwedel when an American tank rolled up. In 1997, from her home in Tel Aviv, she wrote a public letter describing her liberation and thanking the GIs:

A U.S. soldier jumped off the tank, opened the gates and announced, “You are free.” To us, he and the others from the U.S. Army were angels from heaven. I was standing fairly near the gate and tried to say “thank you” in English, German or even Hungarian, but no sound would pass my lips.

I ran back to my room in my hut, where several girls were lying on the floor, burning with fever, some even vomiting blood. I wanted to tell them that we were free, but no sound came out. It seems that the excitement of that morning was too much for my dilapidated condition.

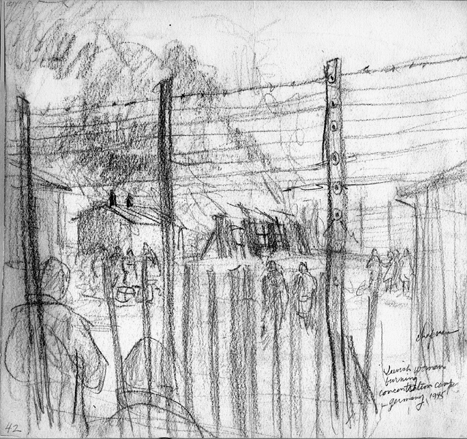

The burning barracks at Salzwedel described by survivor Lea Fuchs-Chayen was sketched by 84th Infantry Division combat artist Walter Chapman

.

For the past 48 hours, we had heard gunfire and that morning, we could hear the noise of tanks. When our liberators arrived, the Germans lifted their hands above their heads in capitulation. A few U.S. soldiers rounded them up. One SS officer started to run away and was shot dead.

The Army organized food for us and told us we would be taken to decent quarters. After we left the infested camp, it was burnt down. A doctor came and took note of the patients who needed hospitalization. About three days later, trucks took us to a German air force training school. The buildings were pleasant and roomy and our liberators had expelled all the cadets, after having made them clean the place for us. We were told not to drag anything and should we want to rearrange our rooms, we should ask a U.S. soldier and he would give orders for it to be done. Each of us received a bar of soap, the first in a year. We had hot water for 24 hours a day and so we could shower three or four times a day, as if to wash away all the mental hurt inflicted by the Germans. We had proper beds with sheets and received clean towels every day. After our first shower, we were asked not to put on our old rags, as they were full of lice. We were given clean clothes.

The U.S. Army had organized a special diet for us as we had to get used to eating again. We had the normal facilities of a dining room and we sat on chairs at tables, like human beings again. There were always several Army people present to make sure that all was well, and all this at a time when the United States was still fighting a war.

The most astonishing thing I found, then and today, was how wonderfully kind they were to us. How remarkable it was that under the dirt, disease, rags and lice, these soldiers could see human beings, young girls. Their kindness and their thoughtfulness gave us back our belief in the human race.

A doctor came around to each room to examine us, recommended treatment or said, with a smile, “You will be fine, miss, with good food inside you again.”

In the evenings, time and time again, there would be a knock on the door and soldiers would come in and do conjuring tricks or other silly things to get us to laugh or at least smile again. It took some time before we learned to smile again.

Today, 52 years after my liberation, I stand in awe and thank you not only for liberating me, but for being so humane, efficient and kind.

God bless you.

Immediately after the liberation of the camp, Ken Ayers remembers seeing the freed prisoners running amok in the streets of the town of Salzwedel. “They were getting hundred-pound bags of sugar and splitting them open with a knife and coming out with double handfuls of it. They were looting stores. One of them brought me the most beautiful accordion you ever saw in your life—they were just looting and giving stuff away.”

Creighton Kerr of Waterford, Michigan, was a machine gunner with D Company of the 333rd Regiment. He was in a jeep driving past the gates of the Salzwedel camp when two GIs came running down the walk inside the gate, calling out to the Americans. It turned out that both men had been captured on the first day of the Battle of the Bulge, both were medic sergeants, and both had been working in the Salzwedel camp hospital. But that’s where the similarity ended: one man asked for food and was given a breakfast K ration, which he sat down on the curb and ate. The other man asked for a weapon. Kerr gave him a carbine with a couple of magazines of ammunition, and the guy disappeared back into the camp.

Kerr’s other memory of Salzwedel was seeing women pouring out of the wide main gate into the street, singing and dancing. One was stark naked—except for several hats piled on top of her head and a green shoe on one foot, a red shoe on the other.

The 333rd spent less than an hour outside the Salzwedel camp. Then they went on to the Elbe River, where they met the Russians and waited for orders. Within days, Kerr was asked to return to the town of Salzwedel to assist the occupying 334th Regiment as a special services officer. His primary job: to keep the former women prisoners from Salzwedel and men who had, presumably, been in smaller slave-labor barracks in the area entertained. He did it by organizing them by country of origin, and each night of the week, a different group would put on a show. The memory that sticks with him? “We had a famous French male singer—I can’t remember his name—who sang the French national anthem for the first time in five years on that first Monday night.”

The women who survived Salzwedel were moved to a nearby German military base, where they were cared for by American soldiers. Several weeks after liberation, three of them made an American flag, which was presented to the 84th Division Railsplitters

.

APRIL 12, 1945

OHRDRUF CONCENTRATION CAMP

M

ore than a week after the liberation of Ohrdruf, on the same day that U.S. Army units were liberating Buchenwald, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied forces in Europe, flew to Ohrdruf because of the unbelievable stories he’d heard. He was met there by Generals Omar Bradley, the Twelfth Army Group commander, and George S. Patton, commanding general of the Third Army, to which the 4th Armored Division, which had discovered the camp, was assigned.

Private Don Timmer, with two years of high school German, was assigned to serve as Eisenhower’s interpreter for the supreme Allied commander’s tour of the Ohrdruf concentration camp. Timmer was nineteen years old

.

Private Don Timmer, a nineteen-year-old kid from Mansfield, Ohio, had just arrived at Ohrdruf with the 714th Ordnance Company of the 89th Infantry Division. Because he’d had two years of high school German, he’d been interpreting for his unit. On the first nice day of spring, they’d driven from Gotha through the town of Ohrdruf, and he remembers that the German civilians had hung white sheets of surrender in their windows. He also recalls a German plane flying low over their small convoy but not strafing them.

As Eisenhower came into the camp, Timmer was told that the general’s interpreter was on a plane that had not yet arrived. Timmer would have to do the job. “I said to him, ‘General, I’m not that good at German.’ And he said, ‘Don’t worry, I know German, but I need time to formulate my responses.’”

So Timmer followed Ike, Bradley, and Patton around the camp, tagging along even after the general’s interpreter arrived. Though some of the bodies had been removed, the ellipse of dead at the entrance had deliberately been left in place, as had the stack of bodies in the shed. Timmer recalls, “The most pathetic thing happened [when] we came into a barracks of maybe five hundred men. There was one that was unconscious, and a fella shook him and said, ‘Eisenhower’s here.’ The guy sat up, smiled, and then fell over dead.”

One of the former prisoners who emigrated to the United States, whose name became Andrew Rosner, had given the generals a tour of the camp. He spoke about the experience in Wichita, Kansas, at a celebration on April 23, 1995, honoring the 89th Infantry Division fifty years after the liberation of Ohrdruf. Rosner was twenty-three when he escaped from one of the SS death marches from the camp. He was found on the outskirts of the town by two American soldiers and hospitalized. Days later, when he awoke, he remembers the nurse running to get waiting American officers and members of the press. He told the Wichita audience, “I was taken back to the concentration camp Ohrdruf by jeep in a convoy headed by Generals Eisenhower and Bradley themselves. Several survivors and myself gave General Eisenhower and his men a personal tour of the horrors, which you had discovered at Ohrdruf. I never forgot how General Eisenhower kept rubbing his hands together as we spoke of the horrors inflicted upon us and the piles of our dead comrades. He insisted on seeing it all, hearing it all. He knew! He wanted to have it recorded and filmed for the future.”