The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (38 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

T

he war in Europe had been ending in piecemeal fashion for almost a week. On April 29, representatives of the German military signed surrender documents for their forces in Italy, effective May 2. On April 30, with the Battle of Berlin raging above and around him, Hitler committed suicide in his bunker. On May 2, the commander of the Berlin Defense Area unconditionally surrendered to the Soviet army. And on May 4, British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery took the unconditional surrender of all German forces in northwest Germany, Holland, and Denmark. (On May 5, Admiral Karl Dönitz would order all U-boats to cease offensive operations and return to their bases.)

Despite these signals that the end of the war was near, American forces in the U.S. Third Army’s XII Corps area came under heavy enemy fire in Linz and Urfahr, Austria. The 71st Infantry Division’s three regiments—the 66th on the left, the 14th in the center, and the 5th on the right—sped southeast by foot and in vehicles to the Traun River, where they took Wels and Lambach as well as the bridges at both cities.

Late on May 4, the cavalry reconnaissance group of the 71st discovered the Gunskirchen concentration camp hidden in a young pine forest so dense the site was almost invisible from the main highway as well as from the air. The camp was relatively new; it had been built by four hundred Polish and Russian prisoners transferred from the Mauthausen concentration camp just five months earlier. At the time of liberation it had eight or nine partially completed buildings used as barracks and was surrounded by an eight-foot-high barbed-wire fence with guard towers positioned along the perimeter. The area inside the fence was wooded.

In the last two weeks of April, three columns of prisoners had been marched from Mauthausen to Gunskirchen to relieve overcrowding caused by the flood of Nazi prisoners arriving from camps farther east. Those who had come from Hungary had been force marched more than 150 miles over mountains and winding roads. The ones who couldn’t keep up were shot. There are reports that somewhere between 15,000 and 17,000 Jews had been crammed into Gunskirchen; barracks that had been built to hold 300 were housing nearly ten times that many prisoners.

In the final days before liberation, food in the camp was minimal, and water was almost nonexistent. Once a day, a fire truck carrying 1,500 liters of drinking water came to Gunskirchen. There was only one latrine for all the prisoners, and the SS guards decreed that it could be used only six hours a day. Prisoners had to line up to use the facility. Diarrhea was rampant. The Germans warned that prisoners caught defecating outside the latrine would be shot on sight.

Shortly after the war ended, the 71st Infantry Division published a booklet titled “The Seventy-first Came … to Gunskirchen Lager.” In it, Captain J. D. Pletcher of Berwyn, Illinois, wrote:

Of all the horrors of the place, the smell, perhaps, was the most startling of all. It was a smell made up of all kinds of odors—human excreta, foul bodily odors, smoldering trash fires, German tobacco—which is a stink in itself—all mixed together in a heavy dank atmosphere, in a thick, muddy woods, where little breeze could go. The ground was pulpy throughout the camp, churned to a consistency of warm putty by the milling of thousands of feet, mud mixed with feces and urine. The smell of Gunskirchen nauseated many of the Americans who went there. It was a smell I’ll never forget, completely different from anything I’ve ever encountered. It could almost be seen and hung over the camp like a fog of death.

PFC Delbert D. Cooper spent the night in Lambach. The Dayton, Ohio, native, whose extended family had seventeen men serving in uniform, was twenty-two years old and a member of Headquarters Company of the 14th Infantry Regiment. He’d joined the 71st as a replacement when the division was still on the other side of the Rhine River. Sixty-three years later, he remembers quite clearly the day he came to Gunskirchen lager.

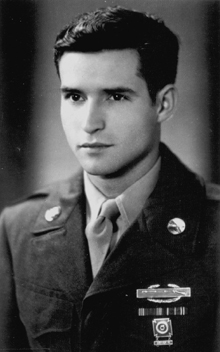

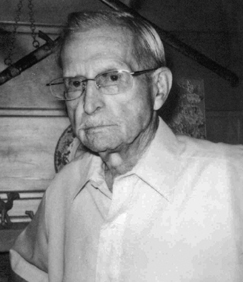

Twenty-two-year-old Delbert Cooper near the end of the war and sixty-three years later

.

“I was looking for some coffee, really. I had spent the night in Lambach, and I went down to the railroad station the next morning, relatively early, and I spotted my captain. I went through the railroad station, just a small place, and I stepped through the door and, going out into the railroad yards, something moved—and I reflexed real fast. I saw a young fella, like a kid, sitting against the wall there, and he was all scurvy-looking. I walked back into the building, and I said to Captain Swope, ‘What is that out there, sir?,’ and he says, ‘There’s a camp, one of those concentration camps, about five klicks down the road.’ A klick was a kilometer. And he said, ‘There’s a truck going to be coming up here with a couple guys. We captured that train out there last night. It’s a German supply train. Would you go out and break open a boxcar and help those guys load?’

“The captain’s talking—I’m a PFC—so I said sure.” Cooper got into the boxcar, which was filled with food, helped load the truck, and figured he’d go along to help them unload. There was Cooper, the driver, a major, and one other GI.

“As we were going along the road past Lambach, we started smelling something and also seeing a lot of people along the road. And they were throwing their hands in the air and prayin’ and all that. We got out where we turned off to go in these woods, and people were just about to mob us, I tell ya. We went on back into the woods—I don’t know how far—a pretty good ways—and people were laying around dead.” What he saw were prisoners who had come into the woods to relieve themselves and dropped over dead.

Cooper was in the camp for several hours, giving him time to explore.

“I remember one old man sitting on a big boulder, farther back from where we were, and I can see right now, throwing his arms up, or his hands up, into the sky and praying. They were saved, and we kept telling ‘em, ‘Look, you’re gonna be safe, we got food, medics will be coming.’ We’ve got to go on—the war was still being fought.”

Cooper, whose father had worked on a railroad, went back to the train station and climbed into the engine that was still hooked up to the captured supply train. He discovered that there was an Austrian woman in the cab, a member of the train crew, and there was still a good fire burning. So he went back to Captain Swope and suggested that rather than running trucks to the camp, they could just move the train down the rail siding that went out to the camp, which is what was done.

Two days later, Cooper had time to write a letter to his wife, Joan. Sitting on an ammo box and using his mess kit as a desk, he told her about Gunskirchen.

Morning Blondie,

Here’s that pest again. Guess it’s been a couple of days since I wrote you. Can’t keep track of the time any more, you know. Just days and nights now. The weather has been pretty bad for sometime now. Rainy and cold, but I’m inside most of the time so it’s not so bad. I have seen the Alps mountains for the past couple of days…. You should see my clothes this morning. I rode on a jeep over these muddy roads yesterday and we didn’t have any top on it…. Incidentally, I helped capture 8 Germans and one SS man yesterday. They are really beginning to give up. (4 hr. break.)

Yesterday I was to a concentration camp. From what I saw with my own eyes, everything I ever heard about those places is absolutely true…. I’m going to tell you now I never want to see a sight again as we saw when we pulled in there. 1400 starving diseased stinking people. It was terrible. Most of them were Jews that Hitler had put away for safe keeping. Some of them had been in camps for as long as 8 years. So help me, I cannot see how they stood it. No longer were most of them people. They were nothing but things that were once human beings. As we pulled off of the highway into the camp, we had to shove them off of the truck. We had the first food that had been taken in there for a month. The people for the most part were dirty walking skeletons. Some were too weak to walk. They had had nothing to eat for so long. Some of them were still laying around dead where they had fallen. They would fall as they tried to keep up with the truck…. You could stand right in front of them and wave your arms for them to move over and they would just stand there, look right in your face and cry like a baby. It was really a pathetic scene. Finally we took out our guns and pointed them in their faces, but they still stood there and bawled. They were past being afraid of even a gun. We fired a few shots up in the air and still we couldn’t clear them. They just couldn’t believe that we had food for everyone.

While we were standing outside the truck, any number of them came up and touched us, as if they couldn’t believe we were actually there. Some of them would try to kiss us even (They must have been bad off.) Some of them would come up, grab you around the neck, and cry on your shoulder. Others would just look and cry. Some of them would throw their arms up in the air and pray. They were mostly the ones who were too weak to stand. I recall one woman who could only cry and point at her mouth. One fellow must have felt that he should give me something. As he had nothing to give of value, he gave me his little yellow star that designates a Jew.

Someone had slipped 500 eggs aboard [the truck]. I took one of the [English-speaking] guys and told him to start with the children and give them one egg apiece and if he had any left over to give them to the women. He told us people were dying off at the average rate of 150 per day at this camp. They just stack them up in a pile if they died in the barracks. If they died outside they left them there. I know, I saw them…. There was human refuse everyplace. I had enough on my boots to be a walking sewer pipe. On top of all this, they had no water…. The young people who were in this camp will probably never get over it. They will be stunted for life.

There are two things about all this that I want to tell you:

I never again want to see anything like that happen to anyone.

I wish 130 million American people could have been standing in my shoes.

Delbert Cooper’s casually tossed off line about helping to capture “8 Germans and an SS man” obscures a dramatic incident that took place less than an hour after he left Gunskirchen to catch up with his unit. He hitched a ride in a jeep, and after a bit, they stopped at a farmhouse to get something to eat. “We just walked in and ordered what they had—if they had anything, we’d just take it. You know how that goes, even in Austria, ‘cause they were still the enemy—however, we did notice a difference in their attitude.

“And there were several German soldiers in there, sitting at the table, and there was a couple of French DPs. One of them said to me, ‘SS.’ I can’t speak French or German, so I told these guys we was with, ‘Hey, this guy says there’s a couple of SS around here.’ Anyway, the SS were the tough guys, and they’d just as soon shoot you as look at you. I had picked up a couple pistols earlier in the war, and I went out with this guy, and he pointed towards the barn.

“I peeked around the corner, and there’s a guy, a young fella, standing out in the barn lot, and he’s bare from the waist up and he’s got civilian trousers on. And this French DP said, ‘SS,’ and I pointed and I said, ‘SS?,’ and he said yeah. So I put my hands behind me with the pistol and I started walking up toward him. He said there was two—there was only one—so I went walking up to this fella and I said to him,

‘Deutsche Soldaten?’

And when I said that, he just kept looking at me, and I whipped the pistol out from behind me and put it right on his chest, and I started to squeeze the trigger. Thank God they were new pistols.”

Cooper says he was hoping that the soldier would make a move, anything to justify shooting him. “I thought, raise your arm. Give me a real excuse to shoot him. Other than that I’m murdering. Anyway, one of the other guys came around the barn, and he said, ‘Shoot the SOB, Cooper.’ And I stepped back a pace, handed the pistol toward him, and said, ‘You shoot him.’ Well, he wasn’t going to murder him either. So I says, ‘We better take him with us.’” Cooper got into the back of the jeep, holding a pistol on the SS man, told the eight other German soldiers to head back down the road, and they left. A short way down the road, they turned their prisoner over to an American MP who was directing traffic and caught up with his unit close to Linz.