The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (37 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Melman recalls that the gates to the camp were open when the GIs arrived, and some of the prisoners walked out of the gate, then walked back in, just to see if anybody would harm them.

As the Americans made their way through the camp, they discovered a mass grave containing as many as two thousand bodies. It was identical in construction to one found at Buchenwald. Melman says prisoners were made to dig a trench perhaps thirty or forty feet long; then a removable barrier was placed at the end. Bodies—some still alive—were tossed into the trench. When more space was needed, the trench was extended beyond the barrier, which was then pulled up and moved.

Melman’s small unit stayed in Ampfing overnight, as did C Company of the 62nd Armored Infantry Battalion. Robert Highsmith, now of Las Cruces, New Mexico, was not quite twenty-two years old when his unit made an overnight stop at Waldlager V. He has just one vivid memory of that moment. “There were about four or five of the prisoners that were standing there. They spoke German, and I spoke English only. Four of them were tall. Their hair was unkempt. They were very, very, very, very skinny. They’d lost a lot of weight, with one exception: there was one of the persons there, he had a haircut, was shaved, skinhead. He was fat. When he smiled, you could see a stainless-steel tooth there in his mouth, and I know to this good day that he was a collaborator, because his physical appearance was so much different from all the others that were there.”

Highsmith, who got a commission after the war and retired as a lieutenant colonel in 1967, recalls moving through the Ampfing camp, his rifle at the ready. “When you’re infantry and on the attack like that, you’re always at the ready, because you don’t know what you’re gonna get when you get into there. Only a few days before we had gone to another prisoner-of-war camp [Moosburg]. We went into that camp, and there were German guards there.” Highsmith chokes up as he recalls finding a soldier from his company in the POW camp. The man had been captured two or three months earlier and had lost almost 40 pounds in the interim. So as he walked through Ampfing with twenty-five or thirty members of his platoon, he was remembering his buddy. “I’m thinking that if there are any German guards there, that we’re going to do everything we can to eliminate them.”

But they found no guards, just prisoners who were nearly dead. “Most of them were emaciated, starved, ill, and as I understand, a lot of them died later, because they had been maltreated, malnourished, and then no medication.”

Karl Pauzar of Dayton, Ohio, was a sergeant in Company A of the 62nd Armored Infantry Battalion when his outfit came upon Ampfing. “We didn’t know anything about it being there. I was in a half-track, come up upon this town, said, ‘Ampfing,’ and there’s this camp. There’s not a guard or anything around it, so I drove around to the right side of it and I saw—this is the only individual I remember—this elderly gentleman, very emaciated. Emotionless. The only thing was a shuffle, blank stare, striped uniform. And he come up to the fence. And I kept going; we were instructed not to give them any food or anything else because of this-and-this. I understand that they dropped some medics off, and they were there about six weeks doing what they could with them.”

Pauzar, who also stayed in the military and retired as a lieutenant colonel, says that staying to help out at the camp just wasn’t their priority at the time. “Oh, no, no. Go, go, go, we had the Germans on the run. We didn’t give them a chance to set their defenses. We just run, run.”

But while some units kept going, the outfits that stopped, even for a few hours, saved lives. Consider Coenraad Rood. Ampfing was his tenth concentration camp since he’d been arrested by the Nazis on April 25, 1942, in Amsterdam. Speaking from his home in White Oak, Texas, between Dallas and Shreveport, Rood recalled that most of the moves from camp to camp were part of the effort to keep prisoners, especially slave laborers, from falling into Allied hands. A week earlier, he’d been at another of the Dachau subcamps, Mühldorf. Asked to evaluate his five days at Ampfing, he says, “They were not too bad compared to what I already experienced.” Here, then, is what he calls “not too bad”:

“We lived practically on the ground, in holes in the ground, with a movable roof over it, and we lived ten to twenty in a ditch, you could say. We came there from several camps, and Ampfing was one of those places where they could place us. We had two camps next to each other; I had to work in Camp Six, but I belonged to Camp Five. Six was already evacuated because the Americans came too close. We were waiting to be evacuated, and at the last moment, that all went into smoke, you can say, because the American Army was faster.”

Coen and his new friend Maupy were assigned to walk each day to Camp Six, where they were to whitewash empty prefabricated huts. The walk gave them a chance to find food along the way, usually potato peels in an adjacent field, which was more than anything being provided to the inmates of Camp Five. During his captivity, the five-foot-eight Coen’s weight had dropped from 143 down to 60 pounds at liberation. They walked between camps without a guard, which, Coen explains, did not offer them an opportunity to escape. “Where should we go, anyway? We were prisoners, we wore prisoner clothes, we were tattooed, we had numbers. The danger outside the camp was very great that we should be detected as prisoners, especially if you were a Jewish prisoner, you know, that’s the end of the day for you.” He said it obliquely, but the danger he refers to is from local German civilians—the same people who would soon protest,

“Nicht Nazi.”

Just a couple of days before the 14th Armored arrived, Coen learned that the Germans were intent on liquidating almost the entire camp population. “There was a roll call early in the morning. It was just as daylight came through, and we had to line up along a rail track that went across the camp from one end to the other. We were about 1,100 or 1,200 men standing there. And the camp commander, which we had barely seen before, talked to us. He said, first, all the Jews from Western Europe have to stand on the side. So we had about sixty men, and he talked to us in German. He explained that he expected that the Americans are coming, and he would leave us. The camp will be evacuated; all the people from East Europe would be removed. And he said, ‘You know what’s going to happen to them.’ He talked openly about it. ‘And you stay here.’ And then the Americans—he talked about the enemy, you understand that? When the enemy was coming, we had to report that we were handled humanely. And if we should tell them how it was, he called it, ‘Where you start lying, we know how to get to you, so you better don’t tell them what actually happens at the camp.’”

Coen said the thousand or so Eastern European prisoners were marched down to the gate. “And they went through, out the gate, and then we heard suddenly like a motor. We heard

tat-tat-tat-tat

, and we thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, they shoot them already. They didn’t even wait until they have them in the woods.’ But it was a motor sound, a motorcycle, and it was the commander and a German officer. He came into the camp and said, ‘Close the doors. The enemy is surrounding the camp. You cannot go nowhere.’” After being sent to a big tent and then a warehouse tent next to the kitchen, they were ordered back to their so-called buddahs—the below-ground hovels about the size of a single carport.

“And we went back,” he recalls, “and I lay down. A few days before, I had lost a very good friend in the camp, and that was tremendous on my mind. He is called Nico, and we were very close. We took always care of each of us in kind of choosing to go to another job; we took care that we were together always. We helped each other, with food and with friendship, mostly. And I had lost him in Mühldorf, where we stayed two and a half days before we reached Ampfing. During an attack from American airplanes.”

Coen tells of being in a truck with many other prisoners when the planes attacked, saying, “I’m the only one not wounded on that truck, although I felt like I was wounded. And that’s when I lost my last friend, together more than two years. And that was still on my mind. When we had to go back to the buddahs and I lay down, I thought, ‘Well, this is the end of it. They are shooting, they are fighting.’ And I was very sick, also, and I felt I was dying. And in that situation, I was liberated.

“I was laying down, losing my conscious. I had the feeling that I was floating through the air, and I knew that this was the end. It was my turn, now, to go, to leave everything.”

That’s when he heard Maupy, who spoke English. “They’re here, they’re here, they opened the gates!” Others yelled, “Americanski are komen!”

More than sixty years later, Coen can still re-create the experiences, almost second by second. “I had a feeling I was floating through the air, looking at myself lying down, and I was yelling at myself. I thought I was yelling, but I don’t think I made any sound. It was like a séance that I float through the air, that I saw myself laying and yelling at myself, ‘Stand up! Go by the people outside.’ And I couldn’t; I couldn’t move. And suddenly I heard, outside the buddah, my friend Maupy, I heard him talking English, saying, ‘Go in there. My friend is dying. He should know that he is free now.’ There was a little trapdoor entrance of the buddah with a hole in it, like a window. And that got dark, and then it opened up, and there was an American soldier there.

“He opened it up, it got lighter inside—I was laying in the dark, in the dirt, and he told me, ‘Come, comrade. You are free now.’ And then I start crying. I try to get to him, but I was, like, paralyzed. So I remember I was crawling over the ground, trying to get to the door. And then he picked me up by the collar of my little jacket, and he hurt me, and he was holding me. I remember I thought, ‘Man, is the man strong.’ And then he looked so clean and well taken care of, and he was full of weapons. And he told me, ‘You are free now, it’s over.’ And I was just laying against him. He was holding me, took me outside, and then he repeated again, ‘You are free now. You understand? You are free.’ As dirty as I was, that soldier, the American solder, kissed me. And I kissed him back, and he was holding me and took me outside and said, ‘See? You are free now.’ And he cried, too.”

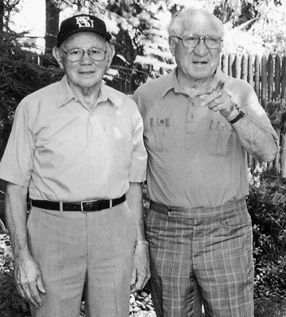

This is the photo that Nathan Melman took of prisoners at Ampfing shortly after their liberation. Coen Rood is in the striped uniform (second from right)

.

There were roughly a dozen American soldiers in the recon squad that discovered Ampfing V. One of them was Nathan Melman, and when Coen and his fellow survivors lined up near one of the jeeps from which the Americans were handing out packages with food, Melman snapped a photo of them that ultimately led to their reunion in the United States.

Coen never did find the soldier who lifted him out of the hole in the ground, but he does tell one amusing story about him. “While he was holding me, he pushed my head back, and he had a bottle with some whiskey or whatever was in there, and he opened up my mouth and poured whiskey in there. And that shot me back. And I could walk.” It was a double shot for Coen, who in the Netherlands had been a member of a youth organization that believed “in pure living, clean living, no alcohol, no smoking. Everything that young people do on street corners, we stayed away from. So I was not used to alcohol.”

Nathan Melman (left) and Coen Rood, reunited in

Shortly after liberation, Coen Rood and Maupy raided the SS kitchen and the homes of their former guards for food and little things like a hairbrush and a pocket knife. They managed to avoid the fighting that broke out between the ex-prisoners and were taken in—certainly with some urging by the Americans—by a local farmer, where they stayed for almost the entire month of May. Eventually, he found his way back to the Netherlands, and in 1959, with the help of a friend who had preceded him, he and his wife—they’d lost their young son in an accident—moved to Shreveport, Louisiana. Eventually they and their two daughters settled in Longview, Texas, where Coen owned and operated his own tailoring business for forty-three years until he retired.

MAY 4, 1945 GUNSKIRCHEN, AUSTRIA

150 miles east of Munich

70 miles east of the Austro-German border

130 miles west of Vienna