The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (40 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Lubin remembered that mayhem going on for quite some time before any of the soldiers really entered the camp. “All the effort was concentrated toward attempting to grab these people. I don’t know why. I didn’t know what else to do.”

Through interviews with the inmates of the camp, they later learned that the guards had left just minutes prior to the arrival of the Americans. “They knew we were coming, and they split. They went out the back door, lickety-split. They didn’t want to be there. One minute they were there, and suddenly the guards were gone. And the people see the guards are gone, and those who were the healthier among them headed for the door. That’s all pretty expected, pretty logical.”

Lubin’s time in Wels stretched to what he thought may have been a few hours, almost all of it spent outside the walls of the camp. A couple of times when the gates were opened, he could peer inside. All he could see was an anteyard, buildings. Other men were assigned to go deep inside. One time he got into the yard area, the compound. “It was crammed with people in all stages of debilitation. Some were relatively healthy-looking, like the first ones I saw up the street at that first encounter. Others were in worse shape, skinnier, more hollowed and hollow-cheek-looking. Others were on the verge of falling down, the bones sticking out of their chests, and others were on the ground. We were trying to pick people up or move them around from one place to another. It was during this time that some kind of order was restored.

“My instinct was to stay, although I didn’t know what the hell I would do if I stayed. But someone’s dying there …” He paused in his narrative; it had become difficult to continue. “My instinct was to help save. These were Hungarian Jews. For those dying, pick them up, hold them, recite the Sh’ma, a Jewish prayer. When somebody is dying you say,

Sh’ma Yis-ra-eil, A-do-nai E-lo-hei-nu, A-do-nai E-chad—

Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One. They told us we had to go. So we went.”

Leonard Lubin had been just another nineteen-year-old kid from Miami. On that day, a day that lasted a lifetime, he became much, much more.

MAY 6, 1945

EBENSEE, AUSTRIA

50 miles west of Salzburg

30 miles south of Gunskirchen

60 miles southeast of Mauthausen

L

eaving the Buchenwald area on April 12, the three infantry regiments of the 80th Infantry Division—the 317th, 318th, and 319th—began what would be a leapfrogging three-week push into Austria. Initially they moved rapidly to the east, taking Jena and Gera; then, closely following the 4th Armored Division, the 319th cleared Crimmitschau and Glauchau in Saxony, while the 318th prepared to take over the bridgehead at Chemnitz, fifty miles southwest of Dresden.

On April 19, the U.S. Third Army was committed to chasing the Germans into Austria, with XX Corps designating the 71st and 65th Infantry Divisions as initial assault forces, with the 80th Infantry and 13th Armored Divisions in reserve. Two days later the 80th changed direction and headed southwest toward Nuremberg to relieve the 3rd Infantry Division. The 150-mile push took a week. On April 28, in order to follow armor in the zone to the right of the 71st Infantry Division, the 80th was relieved in Nuremberg by the 16th Armored Division. Elements of the 318th and 319th once again turned southwest toward Regensburg, passing through the 65th Infantry Division. At this point, the 80th was roughly seventy-five miles north of Munich, which would soon come under attack from divisions moving from the west, rather than from due north.

On April 29, when Dachau was liberated by the 42nd and 45th Infantry Divisions, the 80th completed its crossing of the Danube and elements advanced to Köfering in Bavaria. A day later, the 318th crossed the Isar River over the railroad bridge at Mamming and moved southwest toward Dingolfing. On May 2, with the 318th on the left and the 319th on the right, the 80th Division reached the Inn River in the vicinity of Braunau. The 80th was now midway between Munich and Linz and due north of Salzburg.

On May 3, the 11th Armored Division took Linz, while the 80th overtook the 13th Armored near Braunau. The next day, the 71st Infantry Division, operating slightly south and east of the 80th, sped to the Traun River, taking Wels and Lambach, where concentration camps at Gunskirchen and Wels would be liberated. On May 4, final elements of the 80th got across the Inn, and the 317th attacked to the southeast toward Vöcklabruck. At that point, the division was less than twenty miles from the concentration camp at Ebensee. The five-hundred-mile advance from Buchenwald to Ebensee had taken twenty-two days.

Out in front of the 80th was the 3rd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, which had landed at Utah Beach a month after D-Day and fought at Metz, France, the Siegfried Line, and the Bulge. Robert Persinger, now of Rockford, Illinois, was a twenty-two-year-old platoon sergeant in one of the 3rd Cavalry’s M24 Chaffee light tanks as the end of the war approached. They took their last casualties on May 5, when they engaged a number of Hungarian soldiers fighting in the German army near Vöcklabruck, Austria. One American tank was destroyed, and two men were killed.

That evening they advanced to the town of Gmunden, Austria, at the north end of Traun Lake. The next morning, they were given the mission to enter Ebensee, about ten miles away along a curving, mountainous road at the south end of the lake, to outpost and hold the town until the end of the war. There were no Nazi soldiers defending the town, which Persinger recalls was one of the most beautiful places he’d ever seen. Within hours of arriving, their recon platoon discovered a concentration camp about two and a half miles up the mountain, concealed in a pine forest. His squadron commander ordered two tanks up the hill to the camp gates—one commanded by Persinger, the other by Sergeant Dick Pomante. It was a beautiful, warm, sunny Sunday afternoon as they cautiously went up the winding gravel road.

At about ten minutes to three, Pensinger remembers, he was struck by the smell of death. “We made a right-hand turn into this road, and there, a hundred, two hundred feet away, was this concentration camp. There were people standing behind the barbed-wire fences and the two towers there that were used for the entrance, guarding the gate.” The gate was closed, but the inmates opened it to allow the tanks to drive inside. The Americans would soon learn that the SS had left the day before.

Ebensee was one of the sixty-plus subcamps of Mauthausen, the giant killing facility sixty miles to the northeast. Prisoners from Mauthausen began building Ebensee in November 1943, digging tunnels into the mountains and constructing the future concentration camp. A month later there were more than 500 prisoners in the camp, and the first deaths had already occurred. The SS designed the camp to be built in a thick forest in order to avoid detection from the air. By mid-1944, the crematorium was operational.

The camp was initially populated by Italians and French, but in June 1944 about 1,500 Hungarian Jews arrived from Auschwitz. Then came Soviet prisoners of war, followed by Poles from Auschwitz. Initially, prisoners had been selected for Ebensee who would work effectively digging tunnels into the mountains for various plants, including a gasoline production facility that the American forces would ultimately take over. But in the closing months of the war, prisoners were being sent in open cattle cars from the camps in Poland and northern Germany that were about to be captured by the Russians. Deaths at Ebensee resulted primarily from exhaustion and deliberate exposure to harsh winter conditions. It was the most economical way the Nazis had to kill their prisoners. Roughly 8,000 inmates died at Ebensee, and it’s likely the toll would have been higher but for the fact that seriously ill prisoners were shipped to Mauthausen, which had a greater capacity for processing the dying and dead.

Though acknowledging the horror laid out before them, Staff Sergeant Bob Persinger wasn’t emotionally traumatized by the sight. “We were combat veterans. I saw things I couldn’t imagine on the way to getting there, so it wasn’t too much out of line. It was a horrible sight, but we had been used to seeing horrible sights. We had been in Patton’s Army.”

They had stopped their tanks in the middle of the roll call square and just sat there taking in the scene. “We were looking at thousands of men who were skin and bones, maybe weighing around seventy-five pounds. They were standing in mud that was almost ankle deep, dressed in the striped garment, some with just the trousers, some with just the top, and some with nothing. However, there was so much singing and crying for joy that it was hard to take it all in. We passed out all the rations we had, so a few received a treat that they would never forget, and we felt bad when our supply was depleted.”

Their mission had been to go up to the camp and see if there was any resistance; since there was none, they had no reason to stay. Persinger radioed his lieutenant to ask for orders. But in the meantime, the prisoners were shouting for them to dismount the tanks. What awaited them was difficult. “We knew we were getting into a bunch of filthy human beings, and they were full of lice and fleas and sores and everything else. Of course, we didn’t know, really, how bad, but we heard later that they were loaded with fleas carrying typhoid fever. And they were all over us. They hugged us, doing everything like that.”

A prisoner named Max Garcia who spoke English wanted to guide Persinger and his men on a tour of the camp. They went with him, even though it was emotionally very difficult.

“It was hard to put up with—very hard. Just that alone, but walking amongst the dead bodies and seeing them piled around the crematorium, and then into the crematorium. Things like that was what make you feel much worse than looking at those poor people that didn’t have no garments or [were] starving to death.”

And then they walked into one of the barracks. “Absolutely terrible. People lying on the barracks that would probably be more than half dead, because their eyes never made contact with you at all. Those folks were in very bad shape. Some alive, too, in there. If you were not sick and crying by now, you would be before you exited.”

That evening, they went back down the mountain to the hotel in Ebensee that the American unit had taken over. Their message to the commanders was simple: the people had to be fed, and they were the only ones able to do it. “The following morning,” Persinger says, “we started collecting vegetables, including potatoes, cabbage, and anything that we could use to make a soup from the surrounding countryside.” They gathered food from stores in the area and bread from bakeries. In one case Sergeant Pomante used the big gun on a tank to persuade a village baker that his regular customers would have to wait; that day’s output would go to the prisoners in the concentration camp.

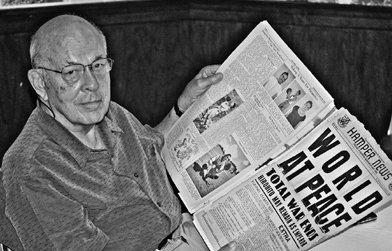

Robert Fasnacht with one of the mementos brought to the 80th Infantry Division reunion at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 2008

.

By evening, they had a large amount of soup and bread to be served but knew the prisoners would be uncontrollable. They planned carefully and used the machine guns on two tanks to fire live ammo over the starving inmates’ heads when they began to overrun the food lines. Persinger says many gulped the soup so fast that they ended up screaming in agony; some became very ill, and some died on the spot.