The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (28 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Not only does the land produce less, but it is less cultivated. In

many places it is not worth while to cultivate it. Large proprietors tired of advancing to their peasants sums that never return, neglect the land which would require expensive improvements. The portion cultivated grows less and the desert

expands.... How can we be surprised that the crops should

fail with such half-starved husbandmen, or that the land

should suffer and refuse to yield? The yearly produce no longer

suffices for the year. As we approach 1789, Nature yields less

and less.

-Jules Michelot

n a telling commentary on pre-industrial French agriculture, historian Fernand Braudel once compared the harvest scene in the fifteenthcentury Heures de Notre-Dame with Vincent Van Gogh's Harvester,

n a telling commentary on pre-industrial French agriculture, historian Fernand Braudel once compared the harvest scene in the fifteenthcentury Heures de Notre-Dame with Vincent Van Gogh's Harvester,

painted in 1885. More than three centuries separate the two scenes, yet

the harvesters use identical tools and hand gestures. Their techniques

long predate even the fifteenth century. As Britain experienced its slow

agricultural revolution, millions of King Louis XIV's subjects still lived

in an agricultural world little changed from medieval times. Hippolyte

Taine wrote of the French poor at the eve of the Revolution in 1789:

"The people are like a man walking in a pond with water up to his

mouth: the slightest dip in the ground, the slightest ripple, makes him lose his footing-he sinks and chokes."' His remarks apply with equal

force to the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries.

The remarkable transformation in English agriculture came during a century of changeable, often cool climate, interspersed with unexpected heat

waves. As farms grew larger and more intensive cultivation spread over

southern and central Britain, famine episodes gave way to periodic local

food dearths, where more deaths came from infectious diseases due to

malnutrition and poor sanitation than from hunger. Britain grew less vulnerable to cycles of climate-triggered crop failure, even during a century

remarkable for its sudden climate swings. France, by contrast, where

farming methods changed little, continued to suffer through repeated local famines during the century.

Wine harvests reflect the vagaries of seventeenth-century climate.

These annual events were of all-consuming importance to those who

lived from the grape or drank wines regularly. They provide at least general information on good and bad agricultural years over many generations.

The date of the wine harvest was always set by public proclamation,

fixed by experts nominated by the community, and carefully calibrated

with the ripeness of the harvest.2 For instance, on September 25, 1674,

the nine "judges of the ripeness of the grape" at Montpellier in the

south of France proclaimed that "The grapes are ripe enough and in

some places even withering." They set the harvest "for tomorrow." In

1718, the harvest date everywhere was earlier, around September 12.

Every year was different, and heavily dependent on the summer temperatures that surrounded the vines between budding and the completion of fruiting. The warmer and sunnier the growth period, the swifter

and earlier the grapes reached maturity. If the summer was cool and

cloudy, the harvest was later, sometimes by several weeks. Of course,

other factors also intervened, as they do today. For example, producers

of cheap wines had little concern for quality and tended to harvest as early as possible. Harvest dates can vary from variety to variety. High

quality wines often benefited from deliberately late harvests, a risky but

potentially profitable strategy widely practiced after the eighteenth century. Still, the main determinants were summer rainfall and temperature.

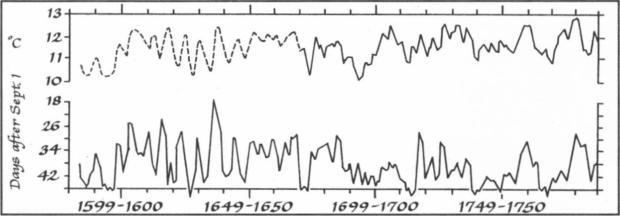

A generalized diagram of the time of wine harvests in southern Europe, 1599-1800,

showing number of days after September I (bottom) and temperature curve (top).

Data compiled from Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, Times of Feast, Times of Famine:A History of Climate since the Year 1000, translated by Barbara Bray (Garden City, N.Y.:

Doubleday, 1971); and Christian Pfister, et al., "Documentary Evidence on Climate in

Sixteenth-Century Central Europe," Climatic Change 43(l) (1999): 55-110

Generations of historians have mined meteorological records, ecclesiastical and municipal archives, and vineyard files to calculate the dates of

wine harvests from modern times back to the sixteenth century. Le Roy

Ladurie has calculated the dates of the wine harvest for the eastern half of

France and Switzerland from 1480 to 1880. Christian Pfister and other

Swiss and German historians are developing highly precise harvest

records for areas to the east.3 Though incomplete, especially before 1700,

these records are sufficient to show a telling pattern, especially when you

compare these dates with the cereal harvests in the same years. Late wine

harvests, from cold, wet summers, often coincided with poor cereal crops.

Bountiful vintages and good harvests indicate warm, dry summers.

Writes Ladurie: "Bacchus is an ample provider of climatic information.

We owe him a libation."4

The wine harvests tell us that the seventeenth century was somewhat

cool until 1609. The years 1617 to 1650 were unusually changeable, with

a predominance of colder summers and relatively poor harvests. Such shifting climate patterns severely affected peoples' ability to feed themselves, especially if they were living from year to year, to the point that

they were in danger of consuming their seed for the next planting in bad

years. A cycle of poor harvests meant catastrophe and famine. France was

coming under increasing climatic stress in the late seventeenth century.

Unlike the Dutch and English, however, the French farmer was much

slower to adapt.

France's rulers, like England's Tudors, were well aware of their country 's

chronic food shortages. Nor were they short of advice as to what to do. At

least 250 works on agriculture appeared in France during the sixteenth

century (compared with only forty-one in the Low Countries and twenty

in Britain), most of them aimed at increasing and diversifying agricultural

production. Some developed ways of classifying soils and methods of

treating them. Others advocated new crops like turnips, rice, cotton and

sugarcane. Praising the humble turnip, one Claude Bigottier was even

moved to verse:

But for all the literary activity, most of France remained at near-subsistence level.

There were pockets of innovation, especially in areas close to the Low

Countries. Market gardeners on the Ile-de-France near Paris planted

peas, beans, and other nitrogen-rich plants, which eventually eliminated the fallow. Elsewhere, specialized and highly profitable crops such

as pastel and saffron were intensively cultivated. With the end of the religious wars in 1595, France entered a period of economic revival, no tably under King Henry IV, who did much to encourage agricultural

experimentation and the widespread draining of wetlands to create new

farmland. He was strongly influenced by the Calvinist Olivier de Serres's masterful Le theatre d 'agriculture, published in 1600, which described how a country estate should be run and suggested innovations

such as selective cattle breeding, that would not be adopted for over

150 years.

Serres opposed the leasing of land to tenants, whom he considered

unreliable and likely to diminish the land's value. He believed an owner

should manage his own land and supervise the workers himself to ensure maximum profit. This would be good insurance against bad years

and reduce the risk of famine and sedition. Serres also had much to say

about labor relations. He believed in harmony on the farm. A

landowner, the paterfamilias, should be industrious and diligent, provident and economical. He had an obligation to treat his workers and

their families charitably and with respect, especially in times of famine

or food shortages. He should have no illusions about wage laborers,

who had to be kept at work constantly, as they were generally brutish

and often hungry.

Although Serres's work was widely read during the seventeenth century, few people followed its recommendations. Most land was leased

out to tenants and sharecroppers, who worked it with the help of their

families and hired help. French agriculture was far from stagnant, but

the indifference of many landowners and the social chasm between those

of noble birth, the rich generally, and the poor made widespread reform

a virtual impossibility. The chasm stemmed from historical circumstance

and ancient feudal custom, from preconceived notions about labor, and

from fear of the poor, who were thought to live "like beasts."