The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (25 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

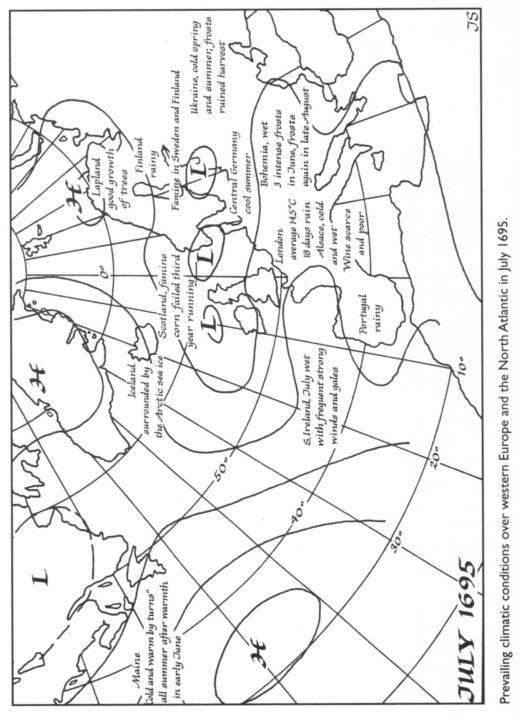

The North Atlantic Oscillation was probably in a low mode, causing a

persistent anticyclone over northern Europe. For weeks, an and northeasterly wind had been blowing across the North Sea, further drying out

an already parched city. The persistent "Belgian winds" had the authorities on high alert, for England was at war with the Dutch and the breeze

favored an attack from across the North Sea. In the small hours of September 2, a fire broke out in the house of the Royal Baker in Pudding

Lane, then burst outward across the street to a nearby inn. By 3 a.m.,

fanned by the strong wind, the fire was spreading rapidly westward.

Flames already enveloped the first of more than eighty churches. The

Lord Mayor of London distinguished himself by observing the fire and

remarking casually: "Pish, a woman might piss it out."2 He returned to

bed while over three hundred structures burned. By morning, the fire was

spreading through the wooden warehouses on the north bank of the river.

Dozens of houses were pulled down in vain attempts to stem the flames.

Huge cascades of fire leapt into the air and ignited roofs nearby, while rumors spread that invading Dutch had started the conflagration. Such fire

engines as there were got stuck in narrow alleys. Samuel Pepys walked

through the city, "the streets full of nothing but people; and horses and

carts loaden with goods, ready to run over one another, and removing

goods from one burned house to another." Hundreds of lighters and

boats laden with household goods jammed the Thames. By dark Pepys

saw the blaze "as only one entire arch of fire ... of above a mile long.

... The churches, houses, and all one fire, and flaming at once; and a

horrid noise the flames made, and the crackling of houses at their ruin."3

The great Fire of London burned out of control for more than three

days, traveling right across the city and destroying everything in its path.

King Charles II himself assisted the firefighters. On September 5, the

northeasterly wind finally dropped, but the fire did not finally burn itself

out until the following Saturday. A hot and exhausted Pepys wandered

through a devastated landscape: "The bylanes and narrow streets were

quite filled up with rubbish, nor could one possibly have known where he

was, but by the ruins of some church or hall, that had some remarkable

tower or pinnacle standing."4 The city surveyors totted up the damage:

13,200 houses destroyed in over 400 streets or courts; 100,000 people were homeless out of a population of 600,000. Astonishingly, only four

Londoners died in the flames. The first rain in weeks fell on Sunday, September 9, and it poured steadily for ten days in October. But embers confined in coal cellars ignited periodically until at least the following March.

No one blamed the long drought and northeast winds for turning London into an and tinderbox. The catastrophe was laid at the feet of the Lord.

October 10 was set aside as a fast and Day of Humiliation. Services were

held throughout the country to crave God's forgiveness "that it would

please him to pardon the crying sins of the nation, especially which have

drawn down this last and heavy judgement upon us."5 The City was rebuilt

on much the same street plan, but with one important difference. A regulation required that all buildings now be constructed of brick or stone.

The late seventeenth century brought many severe winters, probably from

persistent low NAOs. Great storms of wind occasionally caused havoc with

fishing boats and merchant vessels. On October 13, 1669, a northeasterly

gale brought sea floods a meter above normal in eastern Scotland, where

"vessels were broken and clattered.... A vessel of Kirkcaldie brake loose

out of the harbour and spitted herself on the rocks." 6 The land itself was on

the move. Strong winds blew formerly stable dunes across the sandy Brecklands of Norfolk and Suffolk, burying valuable farmland under meters of

useless sand. The sand crept forward for generations. In 1668, East Anglian

landowner Thomas Wright described "prodigious sands, which I have the

unhappiness to be almost buried in" in the pages of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. The sand had originated about eight kilometers

southwest of his house at Lakenheath, where some great dunes "broken by

the impetuous South-west winds, blew on some of the adjacent grounds."

They moved steadily across country, partially burying a farmhouse, before

stopping at the edge of the village of Stanton Downham in about 1630.

Ten or twelve years later, "it buried and destroyed various houses and overwhelmed the cornfields" in a mere two months, blocking the local river.

Some 100,000 to 250,000 tons of sand overwhelmed the village, despite

the use of fir trees and the laying of "hundreds of loads of muck and good

earth." 7 Not until the 1920s was the area successfully reforested.

On January 24, 1684, the diarist John Evelyn wrote: "Frost ... more &

more severe, the Thames before London was planted with bothes [booths]

in formal streets, as in a Citty. . . . It was a severe judgement on the Land:

the trees not onely splitting as if lightning-strock, but Men & Catell perishing in divers places, and the very seas so locked up with yce, that no vessells

could stirr out, or come in."8 The cold was felt as far south as Spain. The

following summer was blazing hot, only to be followed by another bitter

winter with a frozen Thames, then more summer heat. The twenty years

between 1680 and 1700 were remarkable for their cold, unsettled weather

at the end of a century of generally cooler temperatures and higher rainfall.

Wine harvests were generally late between 1687 and 1703, when cold,

wet springs and summers were commonplace. These were barren years,

with cold summer temperatures that would not be equaled for the next

century. The depressing weather continued as the Nine Years War engulfed

the Spanish Netherlands and the Palatinate and Louis XIV's armies battled

the League of Augsburg. The campaigning armies of both sides consumed

grain stocks that might have fed the poor. As always, taxes were increased

to pay for the war, so the peasants had little money to buy seed when they

could not produce enough of their own in poor harvest years.

From 1687 to 1692, cold winters and cool summers led to a series of

bad harvests. On April 24, 1692, a French chronicler complained of "very

cold and unseasonable weather; scarce a leaf on the trees." 9 Alpine villagers

lived on bread made from ground nutshells mixed with barley and oat

flour. In France, cold summers delayed wine harvests sometimes, even into

November. Widespread blight damaged many crops, bringing one of the

worst famines in continental Europe since 1315 and turning France into

what a horrified cleric, Archbishop Fenelon, called a "big, desolate hospital without provisions." Finland lost perhaps as much as a third of its population to famine and disease in 1696-97, partly because of bad harvests

but also because of the government's lack of interest in relief measures.

Unpredictable climatic shifts continued into the new century. Harsh,

dry winters and wet, stormy summers alternated with periods of moist,

mild winters and warmer summers. The cost of these sudden shifts in human lives and suffering was often enormous.

The Culbin estate lies close to the north-facing shore of Moray Firth,

near Findhorn in northeastern Scotland. During the seventeenth century,

the Barony of Culbin was a prosperous farm complex lying on a low peninsula between two bays and curving round to enclose the estuary of

the Findhorn river. The farms were protected by coastal dunes built up by

prevailing southwesterly winds but had long been plagued by windblown

sand, which threatened growing crops. Wheat, here (a form of barley),

and oats grew easily in this sheltered location; salmon runs also brought

prosperity.

In 1694, the Kinnaird family under the laird Alexander owned the

Barony of Culbin and its valuable 1,400-hectare estate. The laird himself

lived in an imposing mansion, with its own home farm, fifteen outliers,

and numerous crofts. A cool summer that year had given way to a stormy

fall. Cold temperatures had already descended on London, where north

and northwesterly winds blew for ten days in late October accompanied

by frost, snow, and sleet. Sea ice had already advanced rapidly in the far

north, propelled by the same continual northerly winds. The bere harvest

was late and the estate workers were hard at work in the fields when,

around November 1 or 2, a savage north or northwesterly gale screamed

in off the North Sea. For thirty hours or more, storm winds and huge

waves tore at the coastal dunes at strengths estimated at 50 to 60 knots,

maybe much higher.

The wind rushed between gaps in the dunes, blowing huge clouds of

dust and sand that felt like hail. Loose sand cascaded onto the sheltered

fields inland without warning. Reapers working in the fields abandoned

their stooks. A man choking with blowing sand fled his plow. When

they returned some hours later, both plow and stooks had vanished. "In

terrible gusts the wind carried the sand among the dwelling-houses of

the people, sparing neither the hut of the cottar nor the mansion of the

laird."'() Some villagers had to break out through the rear walls of their

houses. They grabbed a few possessions and freed their cattle from the

advancing dunes, then fled through the wind and rain to higher

ground, only to find themselves trapped by rising waters of the nowblocked river. The resulting flood swept away the village of Findhorn as

the river cut a new course to the sea. Fortunately, the inhabitants escaped in time. The next day, nothing could be seen of the houses and

fields of the Culbin estate. Sixteen farms and their farmland, extending

over twenty and thirty square kilometers, were buried under thirty meters of loose sand.

A rich estate had become a desert overnight. Laird Alexander was

transformed from a man of property to a pauper in a few hours and was

obliged to petition Parliament for exemption from land taxes and protection from his creditors. He died brokenhearted three years later. For three

centuries, the area was a desert. Nineteenth-century visitors found themselves walking on "a great sea of sand, rising as it were, in tumultuous billows." Hills up to thirty meters high consisted "of sand so light that its

surface is mottled into delicate wave lines by the wind."' I Today there are

few signs of the disaster. Thick stands of Corsican pines planted in the

1920s mantle the dunes, forming Britain's largest coastal forest.

Severe storms continued into the first years of the eighteenth century, culminating in the great storm of November 26-27, 1703. After at least two

weeks of unusually strong winds, a deep low pressure system with a center

of 950 millibars passed about 200 kilometers north of London. The pressure in the capital fell rapidly by some 21-27 millibars. Daniel Defoe remarked in an account entitled The Storm that "It had been blowing exceeding hard ... for about fourteen days past. The mercury sank lower

than ever I had observ'd ... which made me suppose the Tube had been

handled ... by the children."12 Defoe was somewhat of an expert on

storms. He had a bad experience during a tempest in 1695 when he

barely escaped being decapitated by a falling chimney in a London street.

There were numerous casualties on that occasion: "Mr Distiller in Duke

Street with his wife, and maid-servant, were all buried in the Rubbish

Stacks of their Chimney, which blocked all the doors."13 Distiller perished, his wife and servant were dragged from the ruins.