The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (26 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

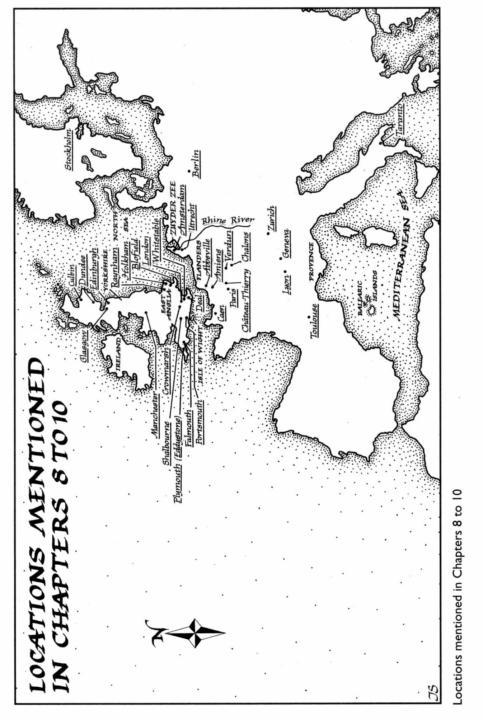

The 1703 storm resulted from a low pressure system that had moved

northeastward across the British Isles to a position off the coast of Norway by December 6. A much severer depression followed from the southwest and progressed across northeast Britain and the North Sea at about

40 knots. Defoe believed that this storm might have originated in a late

season hurricane off Florida some four or five days earlier. He wrote: "We

are told they felt upon that coast [Florida and Virginia] an unusual Tem pest a few days before the fatal [day]."14 He was probably right. The gale

brought exceptionally strong winds, at the surface in excess of 90 knots,

with much more boisterous squalls that may have exceeded 140 knots.

The great storm traveled steadily across south England on the wings of

an unusually strong jet stream. Vicious southwesterly winds blew off

house roofs in Cornwall and toppled dwellings. Defoe tells how a small

"tin ship" with a man and two boys aboard was blown out of the Helford

estuary near Falmouth at about midnight on December 8 by winds estimated to be between 60 and 80 knots. She dashed before the wind under

bare poles on a rush of surface water propelled by the gale. Eight hours

later, the tiny boat, its crew safe and sound, was blown ashore between

two rocks on the Isle of Wight, 240 kilometers to the east. The same

night, enormous waves battered the ornate and newly built Eddystone

Lighthouse off Plymouth Sound and toppled it, killing the keepers and

their families as well as the designer, who happened to be visiting.

In the Netherlands, Utrecht cathedral was partly blown down. Sea salt

encrusted windows in the city, not only those facing the wind, but in the

lee as well. Thousands of people perished in sea surges. Dozens of ships

foundered on Danish coasts, where the damage inland was "gruesome."

Little rain fell despite dark clouds. Fortunately, the storm was followed by

a dry spell. Wrote a Mr. Short: "a happy [circumstance] for those whose

roofs had been stripped."15

The cold weather continued. The winter of 1708/9 was of exceptional

severity throughout much of western Europe, except for Ireland and

Scotland. Even there, severe weather caused major crop failures. Mortality rose sharply in Ireland, where the poor now depended on potatoes.

Fortunately, the Irish Privy Council quickly placed an embargo on grain

exports, saving thousands of lives. Further east, people walked from Denmark to Sweden on the ice as shipping was again halted in the southern

North Sea. Deep snow fell in England and remained on the ground for

weeks. Drought and hard frosts in France killed thousands of trees.

Provence lost its orange trees, and all vineyards in northern France were

abandoned because of the colder weather until the twentieth century.

Seven years later, England again suffered through exceptional cold: 1716

brought a cold January, when the Thames froze so deep that a spring tide

raised the ice fair on the river by four meters. So many people went to the festival that theaters were almost deserted. Most summers in these

decades were unexceptional, but that of 1725 was the coldest in the

known temperature record. In London, it was "more like winter than

summer."16

Then, suddenly, after 1730, came eight winters as mild as those of the

twentieth century. Dutch coastal engineers found wood-boring teredo

worms in their wooden palisades that were the first line of defense against

sea surges. It took more than a century to replace them with stone facings. They also found themselves coping with silting problems in major

harbors and rivers, as well as drinking-water pollution caused by poor

drainage and industrial wastes.

The agricultural innovations of the seventeenth century had insulated the

English from the worst effects of sudden climatic change, but not from

some of the more subtle consequences of food shortages. In late 1739, the

NAO swung abruptly to a low mode. Blocking anticyclones shifted the

depression track away from its decades-long path. Southeasterly air flows

replaced prevailing southwesterlies. The semipermanent high-pressure region near the North Pole expanded southward. Easterly air masses from

the continental Arctic extended westward from Russia, bringing winter

temperatures that hovered near or below zero. Europe shivered under

strong easterly winds and bitter cold for weeks on end.

For the first time, relatively accurate temperature records tell us just

how cold it was. 17 An extended period of below-normal temperatures began in August 1739 and continued unabated until September of the following year. January and February 1740 were 6.2° and 5.2°C colder than

normal. Spring 1740 was dry with late frosts, the following summer cool

and dry. A frosty and very wet autumn led into another early winter. In

1741 the spring was again cold and dry, followed by a prolonged summer

drought. The winter of 1741/42 was nearly as cold as that of two years

earlier. In 1742, milder conditions finally returned, probably with another NAO switch. The annual mean temperature of the early 1740s in

central England was 6.8°C, the lowest for the entire period from 1659 to

1973.

In 1739, Britain's harvests were late due to unusually cold and wet conditions that caused considerable damage to cereal crops. In northern

England, "much Corn, and the greatest part of Barley [was] lost."18 English grain prices rose 23.6 percent above the thirty-one-year moving

average in 1739, partly as a result of the deficient harvest, especially in the

west where September storms damaged wheat crops. The cold weather

caused exceptionally late grain and wine harvests over much of western Europe. Western Switzerland's cereal harvest did not begin until about October 14, the second latest from 1675 to 1879. Ice halted Baltic shipping by

late October and rivers in Germany froze by November 1. All navigation

on the River Thames ceased between late December and the end of February. Violent storms, wind, and drifting ice cast lighters and barges ashore.

Ice joined Stockholm in Sweden with Abo across the Baltic in Finland. The

rock-hard ground bent farmers' plows. Because they could not turn the soil

for weeks, winter grain yields were well below normal in many places.

There was no refuge from the cold, even indoors. Early January 1740

brought savagely cold temperatures. The indoor temperatures in the

well-built, and at least partially heated, houses of several affluent householders with thermometers fell as low as YC. Few of the poor could afford coal or firewood, so they shivered and sometimes froze to death,

huddled together for warmth in their hovels and huts. Urban vagrants

on the streets were worst off, for they had nowhere to go and the rudimentary parish-based welfare system passed them by. Wrote the London

Advertiser. "Such Swarms of miserable Objects as now fill our Streets are

shocking to behold; many of these having no legal Settlements, have no

Relief from the Parish; but yet our fellow Creatures are not to be starved

to Death; yet how are they drove about by inhuman Wretches from

Parish to Parish, without any Support."19 The Caledonian Mercury in

Edinburgh wrote of. "the most bitter frost ever known (or perhaps

recorded) in this part of the World, a piercing Nova Zembla Air, so that

poor Tradesmen could not work ... so that the Price of Meal, etc. is

risen as well as that of Coals."20

Thomas Short summarized 1840 aptly: "Miserable was the State of the

poor of the Nation from the last two severe Winters: Scarcity and Dearth

of Provisions, Want of Trade and Money."21 Thousands died, not so

much from hunger but from the diseases associated with it, and from extreme cold.

By 1740, infectious diseases like bubonic plague were no longer a major cause of death in western Europe. The higher mortality of dearth years

resulted primarily from nutritional deficiencies that weakened the immune system, or from social conditions that brought people into closer

than normal contact, where they could be infected by various contagions.

Everywhere in eighteenth-century Europe, living conditions in both rural

and urban areas were highly unsanitary. Chronic overcrowding, desperate

poverty, and ghastly living conditions were breeding grounds for infectious diseases at any time, even more so when people were weakened by

hunger. In preindustrial England, for example, mortality rates increased

more as a result of extreme heat and cold.22

Most of these deaths came not from chronic exposure, which can affect

seamen and people working outside at any time, but from a condition

known as accident hypothermia. When someone becomes deeply chilled,

blood pressure rises, the pulse rate accelerates, and the patient shivers

constantly, a reflex that generates heat through muscle contraction. Oxygen and energy consumption increase, and warm blood flows mainly in

the deeper, more critical parts of the body. The heart works much harder.

The shivering stops when body temperature falls below 35'C. As the

temperature drops further, blood pressure sinks, the heart rate slows.

Eventually the victim dies of cardiac arrest.

Most accidental hypothermia victims are either elderly or very young,

caught in situations where they are unable to maintain their normal body

temperature. Fatigue and inactivity, as well as malnutrition, can hasten

the onset of the condition. Few houses in the Europe of 1740 had anything resembling good heating systems. Even today, hypothermia can kill

the elderly in dwellings without central heating when indoor temperature

falls below 8°C. As many as 20,000 people a year died in Britain from

this condition in the 1960s and 1970s, almost all of them elderly, many

malnourished. Conditions were unimaginably worse in 1740, even in the

finest of houses, where warmth was confined to the immediate vicinity of

hearths and fireplaces. The newspapers of 1740-41 carry many stories of

death from the "Severity of the Cold."23

At the same time, the sharp temperature changes brought increases in

pneumonia, bronchitis, heart attacks, and strokes. The elderly in particular have a reduced ability to sense changes in temperature, and thermal stress can also lower resistance to infectious diseases. The London Bills of

Mortality for the first five months of 1740 show a 53.1 percent rise in the

number of registered deaths over the same period in the previous year. A

breakdown of the mortality data shows climbs in all age groups, with the

largest increase (over 97 percent) in the group over sixty years of age.

Many of the hungry were also killed by famine diarrhea, a condition

resulting from prolonged malnutrition and pathological changes in the

intestines that upset the water and salt balance in the body. The diarrhea

often began after the victims ate indigestible food or the rotting flesh of

dead animals. As starvation persisted and they continued to lose water

through their bowels, the sufferers lost weight until they died in a state of

extreme emaciation. Famine diarrhea was common in World War II concentration camps. Long periods of food dearth also produce many cases

of what is sometimes called "bloody flux," owing to the passing of blood

in the victim's watery stools.

Cycles of colder, wetter, or drier years with their bad harvests had a direct health effect. Any serious food shortage penetrated to the heart of

rural and urban communities, throwing thousands onto the inadequate

eighteenth-century equivalents of the welfare rolls. The hungry would often abandon their homes and villages and congregate in hospitals or poorhouses, where sanitary conditions were appalling. Crowded prisons were

also hotbeds of infection, as were billets used by military units. Under

these conditions, epidemics of louse-borne typhus infections, relapsing

fever, and typhoid fever flared up, especially in colder climates, where malnourished people huddled together in crowded lodgings for warmth.

When the destitute died or sold their possessions, their clothing, and even

underwear, were passed on to others, together with the infections that lay

within them.

Unemployment, hunger, and war nourished typhus in particular. A

fierce epidemic raged in Plymouth in southwestern England in early

1740, reaching a peak during the summer months. By 1742, the disease

had spread throughout the country. Devonshire in the west suffered

worst. Physician John Huxham observed the epidemic at firsthand and

wrote: "Putrid fevers of a long Continuence ... were very rife among the

lower Kind of People.... Some were attended with a pleurisy, but those

destroyed the Patients much sooner." Another physician, John Barker, at tributed the epidemic to the bad weather and harvest shortfalls, exactly

the same conditions, he remarked, as those during the outbreak of

1684/85.24 Typhoid and typhus fever killed hundreds of the poor in

County Cork, elsewhere in southern Ireland, and in Dublin.