The Mapmaker's Wife (33 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

Fiedmont laid out his doubts to Jean. The arrival of the 12,000 settlers in Kourou, he said, was causing “much suspicion and distrust” among all of French Guiana’s neighbors. Jean could go with Rebello, but he should know that nobody in France had told him to expect the Portuguese boat. How could the king of Portugal order such a thing without first informing Paris?

The galliot departed from Cayenne in late November 1765 with a nervous Jean on board. Perhaps, he thought, his letter to d’Herouville had finally borne fruit. Perhaps the “generous nobleman” had gone to Choiseul and that had set off a chain reaction: Choiseul had written to the Portuguese ambassador, the ambassador to Portugal’s king, and the king to Pará. That was certainly possible. But on the way to Oyapock, where they planned to stop for a short while so that he could tie up some loose ends, Fiedmont’s suspicions fed his own, and he began to panic. He was alone among the Portuguese,

“in the midst of a nation against which I have worked so hard,” he told himself. He would engage Rebello in talk, and it seemed that the Portuguese captain responded with slightly malevolent double entendres.

“Something is going on in this boat,” Jean worried, and then, just before they reached Oyapock, he and the captain had a conversation that seemed to confirm his worst fears. He had told Rebello that in Oyapock he would like to pick up “a Negro and a couple of whites” to accompany him on the journey, and yet the captain had refused. There might be room for a Negro or two, but not for a white. What was Jean to make of this?

“The whites that I would have brought along are not great persons,” Jean told Rebello. “They would have found enough space.”

Jean did not know what to do. When they docked in Oyapock, he decided to stall for time. He tried to keep his suspicions from Rebello—he did not dare chase this boat away—and yet he feared

that if he went upriver, his life would be in danger. It all made sense.

“I’ve worked against this nation and I must scrutinize the tiniest things,” he confided to Fiedmont in a letter. “I fear my letter [to Choiseul] has not been delivered; it has fallen into foreign hands and I am lost. Who will assure me that some evil soul has not turned this to his profit in the [Portuguese] Court?” Jean feigned that he was ill, and told Rebello that he had suffered a

“nasty fall in the woods while going to the lumberyards of my Negroes.” It could be a month or more before he could travel.

While waiting for Fiedmont to reply, Jean came up with a new strategy to divine Portugal’s true motives. Rebello was eager to depart—a number of his oarsmen had fled to the woods in a bid for freedom—so Jean suggested that Rebello proceed to Pará without him. When Jean recovered his health, he would come to Pará to “take advantage” of the king’s “generous” offer to transport him up the Amazon. But Rebello’s answer once again convinced Jean that something was amiss:

“He’ll hear nothing of going ahead, and responds that he must, at all costs, conduct me [to Pará] for that is why he came here,” Jean told Fiedmont.

“This man wants to overpower me here. What will they do when they are in their home territory?”

Jean wrote this last letter to Fiedmont on December 28, 1766. He felt utterly paralyzed. He feared that if he went with the Portuguese, he would be murdered or imprisoned as a spy. But if he let the galliot go without him, his hopes of ever seeing Isabel again would vanish.

“Please do me the honor, Sir, of giving me your thoughts on this matter,” he begged Fiedmont. The governor, though, was tired of the whole affair. He wanted the galliot gone from French Guiana. Jean needed to make a decision. Either go or not go. At last, Jean came up with a compromise proposal for Rebello. Since he remained too “ill” to go, could he instead send a friend of his,

“to whom I might entrust my letters, and who might fill my place in taking care of my family on its return?”

Much to Jean’s surprise, Rebello agreed. And once he did, Jean’s fears began to vanish. He now saw everything in a different light.

He reasoned that he could thank d’Herouville for his change in fortune. It was due “to the kindness of this nobleman” that the ship had arrived. Quickly, he selected a long-time friend, Tristan d’Oreasaval, to go in his stead. He provided d’Oreasaval with money for the journey and a packet of documents, which included letters to his wife and the recommendation that he had obtained in 1752 from the father general of the Jesuits. He had safeguarded Visconti’s letter for so many years, always praying that the day would come when he could use it. The plan was straightforward. Rebello would escort d’Oreasaval to Loreto, the first mission in Spanish territory. After dropping him off, Rebello would retreat across the border to Tabatinga, a Portuguese mission, and patiently wait there. From Loreto, d’Oreasaval would canoe 500 miles upriver to Lagunas, the capital of the Maynas district in the Quito Audiencia, and hand the letters to the father superior. The Jesuits would then carry the packet to Isabel in Riobamba.

Everything had fallen into place. Jean felt his hopes soar, and on January 25, 1766, the galliot sailed from Oyapock. In seven months or so, it would reach Loreto, and this vessel, as Jean now happily declared, was under the command of a military officer who was nothing less than a

“knight of the order of Christ.”

T

HE RUMOR THAT ARRIVED

nine months later in Riobamba was so vague as to be almost cruel. Isabel’s brother Juan had heard it first, that a vessel

might

be waiting for them at Loreto, and that Jesuits

might

be in possession of letters from her husband, who—or so it was rumored—was alive and living in French Guiana. Isabel and Carmen had clung to each other; could this be true? Juan went to Father Terol, the priest who had married Isabel and Jean, to find out what he could, and together the two priests called on Jesuits in Quito. With the Jesuits’ assistance, they were able to piece together a trail of sorts. A man named Tristan had delivered letters to a Father Yesquen in Loreto, who had handed them off to a second priest, who had given them to a third, and now these documents

were quite lost. But while the Jesuits were certain that letters of some sort had been sent Isabel’s way, they were of two minds about the vessel. Some, Juan told his sister,

“give credit to [it], while others dispute the fact.”

Isabel did the only thing she could. She sent a trusted family slave, twenty-three-year-old Joaquín Gramesón,

*

to investigate. He left in January 1767 and returned three months later, exhausted and with no news at all. Authorities had ordered him back to Riobamba because he lacked the proper papers for travel into the Amazon. After resolving that problem, Isabel sent him out once again. It was close to 2,000 miles to Loreto and back, and twenty-one months passed before Joaquín returned. But this time he brought back certain news: He had personally spoken to d’Oreasaval, a boat was indeed waiting for her and Carmen, and Jean was indeed anxious for them to arrive in Cayenne.

This was the news that Isabel had been waiting to hear for so long … and yet by the time Joaquin returned, it was bittersweet. While he had been gone, Carmen—in April 1768—had died of smallpox. Isabel’s hope was always that she, Jean, and Carmen would

all

be reunited. When Joaquin had left on his journey, Carmen had asked Isabel to tell her once more the stories she had heard as a child about her father and about how he and her mother had met. And now Isabel knew for sure that Jean had come back to get them, yet Carmen lay buried in the local cemetery, her nineteen years framing the time that she and Jean had been apart.

The decision that Isabel now had to make was not a simple one. A boat may have been waiting for her, but if she were to go, she would be leaving behind all that she had ever known. Her father, her two brothers and her sister, and her nephews and nieces all lived in and around Riobamba. Her children were buried here. This was her home. And to leave meant going on a journey that no woman had ever dared undertake, and one that her family was insistent that she not attempt.

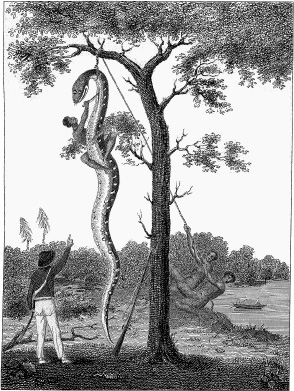

The skinning of an Amazon snake.

From John Pinkerton, ed

., A General Collection of the Best and Most Interesting Voyages and Travels in All Parts of the World,

vol. 14 (London, 1813)

.

To the colonial elite living in the Andes, the jungle was a place populated by savage Indians, terrifying beasts, and deadly disease. The wild Indians in this region, Ulloa and Juan had written,

“live in a debasement of human nature, without laws or religion, in the most infamous brutality, strangers to moderation, and without the least control or restraint of their excesses.” There were also “tigers, bastard lions, and bears” to worry about, and poisonous snakes like the cobra and the maca. This latter reptile, Ulloa and Juan reported, was

“wholly covered with scales and makes a frightful appearance, its head being out of all proportion to the body, and it has two

rows of teeth and fangs like those of a large dog.” Most frightening of all was a man-eating snake that the Indians called jacumama:

It is a serpent of a frightful magnitude and most deleterious nature. Some in order to give an idea of its largeness, affirm that it will swallow any beast whole, and that this has been the miserable end of many a man. … They generally lie coiled up and wait till their prey passes near enough to be seized. As they are not easily distinguished from the large rotten wood, which lies about in plenty in these parts, they have opportunities to seize their prey and satiate their hunger.

*

As for the terrain, all of the routes to the Amazon were

“extremely troublesome and fatiguing, from the nature of the climate and being full of rocks, so that a great part of the distance must be travelled on foot.” These difficulties had scared Maldonado’s family thirty years earlier when he had been contemplating his trip to the Amazon, and if anything, the trek had since grown more dangerous. Indians throughout the viceroyalty were rising up in protest and had fled in significant numbers into the jungle, emerging periodically to attack outlying Spanish towns. Equally problematic, the Jesuits had recently been expelled from Peru, and it was their mission stations that had been the lifeline through this wilderness.

The expulsion of the Jesuits had been a long time coming. They had come to the New World in 1549 to convert the “heathens,” and this missionary work had often put them into conflict with colonists seeking to exploit or enslave the Indians. The Jesuits had also grown very wealthy in their two centuries in the New World, adding to their predisposition to ignore governmental orders.

Portugal ordered them out of Brazil in 1759, and eight years later Spain did the same. While other clergy had replaced the Jesuits in the mission stations along the Amazon, these priests and monks were—as Ulloa and Juan wrote—often utterly shameless in their behavior. Those living in the cities kept concubines, held drunken revelries, and exploited the Indians for financial gain, and these were the religious men that a traveler to Loreto would now have to depend on.

To most in Riobamba, it was inconceivable that a woman would even think of making this trip. Not only did the many physical dangers cry out for Isabel to stay, but cultural norms were an even more powerful restraint. To go would violate values so deep in the Peruvian psyche that they could be traced back to the Reconquest. A woman ventured outside with a maid or a servant by her side or with her husband for an evening of entertainment, and then she scurried back inside. As a descendant of the Godin family would later write:

“Her father and her brothers opposed her going with all their power.”

On the other side of the equation, there was only this: The memory of a husband that Isabel had last seen and held twenty years before.

There was much that Isabel had to do before she could depart. She sold her house in Riobamba and her furniture, and made a gift of her other properties—

“a garden and estate at Guaslen, and another property between Galté and Maguazo”—to her sister, Josefa. There were also supplies to buy and her many personal belongings to pack. This all took several months, and once her family understood that they could not dissuade her, they rallied to her side. Both of her brothers decided that they would accompany her to Loreto and travel on to Europe. Juan obtained permission from his superiors to go to Rome, while Antonio—newly freed from bankruptcy jail—saw the journey as an opportunity to start a new life. He would take his seven-year-old son Martín with him to France, and once they were settled, he would send for his wife and his other son. Joaquín, the family’s most trusted slave, would go

with them to Loreto—Isabel promised to give him his “card of liberty” as a reward once they reached that point. She would also be accompanied by her two maids, Tomasa and Juanita, who were eight or nine years old. Meanwhile, her sixty-five-year-old father decided that he would leave ahead of the others and arrange for canoes to be ready for them as they proceeded from mission station to mission station. He would travel all the way to Loreto and wait there until he knew that his daughter had reached the Portuguese galliot safely. Then he would return to Riobamba.