The Mapmaker's Wife (34 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

News of Isabel’s trip quickly spread throughout the audiencia and beyond. Men and women alike began to gossip about the “lady” who was heading off into the Amazon, and in early September this brought to Riobamba an unlikely visitor: A French man named Jean Rocha, who claimed to be a doctor. He had been making his way up the Peruvian coast, with plans to cross Panama and return to Europe via that route, when, on a stop in Guayaquil, he had heard about Isabel’s trip. He was accompanied by a traveling companion, Phelipe Bogé, and a slave, and in return for passage with Isabel, he promised

“to watch over her health, and show her every attention.” Isabel initially turned him down—her instincts said that he was not to be trusted—but her brothers convinced her otherwise, telling her that she

“might have need of the assistance of a physician on so long a voyage.”

The traveling party was now set: They numbered ten in all, and Isabel hired thirty-one Indians to carry their goods and supplies. The mules were loaded, the people of Riobamba came out to see them go, and Isabel—on the morning of October 1—picked up the hem of her dress and stepped into a waiting sedan chair. The sky was a brilliant blue, the air crisp and clear, and the group headed north out of town, toward snow-capped Mount Chimborazo. The road climbed to the top of a ridge, and once they had left the last houses behind, Isabel summoned up every bit of her will and turned her sights firmly to the east, toward the high cordillera and the jungle beyond.

*

Paris’s silence toward its overseas possessions was apparently common. In 1757, the governor of Louisiana complained that he had written fifteen letters without having receiving a single response from Paris.

*

This seems surprising until one considers how difficult it would have been for Jean to send a letter from French Guiana to Riobamba. He could not send one to Pará in the hope that it would be passed upriver, for the border between Portugal and Spain on the Amazon was closed. One possibility would have been to send a letter from French Guiana to France, with the thought that it could then be passed on to Spanish officials, who could place it in the care of a Spanish trading vessel, which could carry it to Cartagena or Lima; from there the letter could somehow be taken overland to Riobamba. This was a postal system that was almost certain to break down, and even if it did not, a letter could take years and years to be delivered. Jean’s father died in 1740, and yet his siblings’ letter informing him of the death did not arrive until 1748, and that letter had originated in France.

*

Étienne-François de Choiseul served as France’s minister of foreign affairs from 1758 to 1761 and from 1766 to 1770. He was minister of the marine from 1761 to 1766, and during this period his cousin, Cesar-Gabriel, Duc de Choiseul-Praslin, was minister of foreign affairs. However, Étienne-François retained his authority to formulate foreign policy while his cousin served in that position.

*

Slaves often took the surname of their owners.

*

Today we know this snake, the jacumama, as an anaconda, which is the largest member of the boa constrictor family of snakes. The maca described by Ulloa was a pit viper of some type, perhaps the fer-de-lance or the bushmaster.

I

SABEL AND THE OTHERS

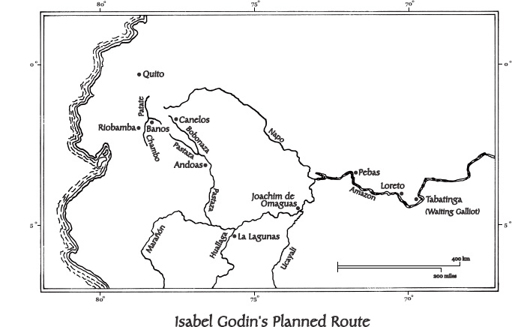

knew that the most difficult and dangerous part of their journey would be the first 350 miles. They would travel overland down the steep eastern slopes of the Andes, from Riobamba to Canelos, and then they would canoe 225 miles down the turbulent Bobonaza River, from Canelos to Andoas. At that point, they would be on the broad expanses of the Pastaza River, and although the Pastaza below Andoas had its share of whirlpools and strong currents, canoes could traverse it fairly easily. They expected to take twelve days or so to reach Canelos and then another two weeks to make it to Andoas. Before the month was over, they hoped that the worst part of their journey would be behind them.

Isabel, who had traveled very little in her life, found the first few days delightful. Once they had turned their backs on Mount Chimborazo and headed east, they began following the Chambo River, one of a handful of rivers in the entire Andean valley that cut through the eastern cordillera and drained into the Amazon. They crossed the Chambo on their second day out, entering into the

mountains, and with the river now on their left and far below them, they picked their way across a steep slope. Mount Tungurahua, its top half covered with ice and snow, loomed ahead. The summit of the great volcano topped out at 16,465 feet, and Isabel, who had seen it from afar so many times, was awestruck by its size and air of hidden power. The graceful and slender Tungurahua she had always known, the petite “wife” of Chimborazo, now seemed fierce and threatening, holding within the furious fires of the earth. As they worked their way north around its lower slopes, at an altitude of about 8,000 feet, they had to struggle to cross gullies cut by water tumbling down from the ice fields above. Each time they came to one, they had to climb higher up Tungurahua’s slopes until the gully narrowed enough that their Indian servants could throw a small bridge across it. Then they would descend the mountainside on the other side of the gully, to where the slopes of the volcano were not quite so steep, and proceed on their way. Although this was slow going, the air was cool, and they were hit by only an occasional burst of icy rain. Each night the Indians built them a shelter of tree branches and cooked a hearty meal over a fire. They had brought along several live chickens and an ample supply of dried corn, beans, potatoes, and dried meats—llama, sheep, and pig. Most likely, this trip was the first time that Isabel had ever slept outdoors.

On the fourth or fifth day of their journey, Isabel and the others reached the small town of Baños, perched on a shelf of land at the base of Tungurahua, about 250 feet above the Pastaza River. The Pastaza is formed by the merger of the Chambo and Patate Rivers a few miles above Baños, and it is a violent, turbulent river, hurling its way out of the Andes with a fury.

Since leaving Riobamba, they had traveled about fifty miles and dropped 3,000 feet in altitude, and they had now entered the cloud forest that covers the eastern slopes of the Andes, a lush world of moss-covered trees, delicate orchids, and hanging vines. There is no other place on the planet where massive snow-capped mountains so closely overlook steaming tropical forest, the two disparate climates separated by less than 150 miles. In rapid order, the alpine world of the mountains turns into a dense forest perpetually bathed in clouds and fog, and then, at 3,000 feet above sea level, the cloud forest gives way to a rain forest, where although it may rain nearly every day, clouds are not constantly present. At an altitude of about 1,000 feet, the vegetation undergoes a further change, into lowland rain forest. For every 1,000-foot drop in elevation, the temperature rises about 4 degrees Fahrenheit, such that it will be fifty degrees colder on the slopes of Tungurahua than it is at the headwaters of the Amazon, only 100 miles away. As a result of these extremes in temperature, the terrain in between receives more than 160 inches of rain a year.

The airflow that drives this wet climate originates in the Amazon basin. Along the equator, heat builds up each day and the warm air rises. Evaporation fills these currents with moisture, and as the air rises, it cools, the water condensing and falling as rain. While this cycle keeps the Amazon basin well watered, prevailing air currents bring a double dose of rain to the eastern slopes of the Andes. Moisture-laden clouds ascending from the jungle floor are pushed by prevailing winds toward the west, where they run smack into the Andes, and as the clouds rise up the slopes, they cool and the rains come. The Andes act as a moisture trap for the entire Amazon basin, and this brings showers to the region more than 250 days a year. It also bathes the mid-level slopes of the Andes, where Baños is located, in a perpetual mist, except for brief periods in the morning, when dawn may break clear.

The constant watering produces a profusion of plant life, every tree covered with ferns, lichens, and other parasitic growth. The entire forest drips moss, and even the tree tops, as the nineteenth-century naturalist Alexander von Humboldt exclaimed, are

“crowned with great bushes of flowers.” Brightly colored birds, such as the golden tanager and the crimson-breasted woodpecker, find this world a paradise, as do bands of gibbering spider monkeys and such reclusive animals as the spectacled bear. But the thick vegetation,

which is draped across the steep cliffs and crags of the Andes, makes this region almost impenetrable to humans. As travelers try to hack their way through the forest, they must cope with constant downpours that turn every path into a muddy quagmire. One stream after another has to be crossed, torrents racing down the mountainside, filled with snowmelt and the daily deluge of rain. This was the very region where Gonzalo Pizarro and his men got bogged down in 1541, when they set out for Canelos, the land of the cinnamon trees.

Isabel and her brothers did not tarry in Baños, stopping only long enough to purchase some additional food supplies and to enjoy a night of rest under a roof before plunging into the cloud forest. Barely had they started on their way before they had to confront the raging Pastaza. About three miles below the village, the river passed beneath two cliffs forty feet apart. They had to cross over on a bridge that consisted of three tree trunks that stretched from one cliff to the other. Thirty feet below, the river crashed against the rocks, throwing up a spray that kept the logs slick and wet.

*

Once they passed that peril, they began making their way along a narrow, muddy path that ran high above the river, just above the canyon cut by the Pastaza. Every few miles or so, they came to a stream cascading down from the mountains to the north. At times, the sheer beauty of the cascading waterfalls caught everyone’s breath, one river after another spilling down the steep mountainside and then, at the rim of the canyon, leaping outward into a free fall, dashing onto rocks hundreds of feet below.

Each time they came to one of these rivers, they had to stop and find a way to ford it. A few were small enough that a log could be placed from bank to bank, but the Indians needed to cobble together bamboo bridges to navigate the wider ones. To do so, they would cut long poles of bamboo from the forest and drop one pole across the river. An Indian would shimmy along it, dragging a liana rope

with him. Once on the other side, he would use the liana to bring a second bamboo pole alongside the first. Then two or three more would be positioned in this manner and lashed together. The sure-footed Indians would cross the bridge loaded down with the goods or carrying Isabel in her chair, the bamboo bending slightly under their weight but never breaking.

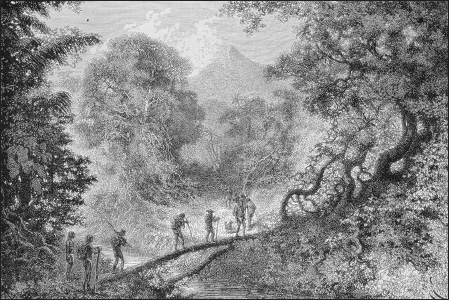

Crossing a log bridge over a river in the jungle.