The Mapmaker's Wife (37 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

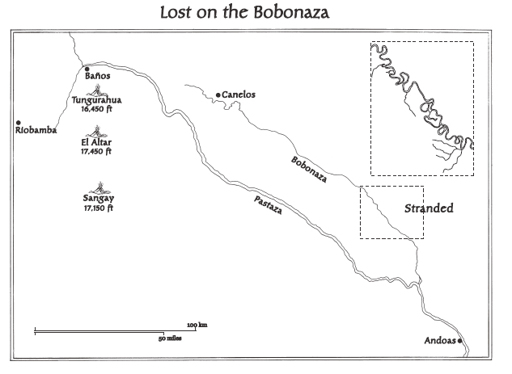

A hut on the lower Bobonaza.

Drawing by Ingrid Aue

.

As the sun rose, however, the air would turn humid and oppressive. By midday, the sand would be hot to the touch, so much so that it would be difficult to cross barefoot. There was nothing for them to do but hide out in shade of their hut, no one saying much of anything. More often than not, the heat would give way to an afternoon rain, and when the rain ceased, the sand flies, gnats, and mosquitoes would come out. These insects pestered them as they pestered all who came through here: Isabel and everyone else scratched their bites, which became infected, their legs in particular becoming covered with the painful sores.

At dusk, the jungle would begin to resonate with the nerve-racking shrieks of howler monkeys and the whoosh-whoosh of bats—sounds that had become familiar and yet were still unsettling.

And as night fell, Isabel and the others would struggle to put down thoughts of caimans, jaguars, and snakes creeping through the darkened foliage, only a few yards away from their hut. They worried too that the Jibaros would discover their campsite and swoop down upon them while they were sleeping. Although the Quechua Indians in Canelos and Andoas were not to be feared, the Jibaros were, and they were known to haunt both sides of this river. When Spruce came to this region, his Quechua guides slept with

“lances and bows and arrows at the head of their mosquito nets, so as to be ready in case of an attack,” while Spruce would only “go ashore with firearms.” The Jibaros were the “naked savages” that La Condamine had written about, a tribe said to “eat their prisoners.”

Isabel and the others passed a week in this anxious manner, and then a second. As the days passed, they began to grow weaker, the heat sapping their strength. During the long midday hours, they would all rest in the shade of their hut, and even though their throats would become parched with thirst, nobody would stir, as though the trip across the sand to the river would be too taxing. The jungle, meanwhile, was

literally

closing in on them: The rising river had narrowed their beach. Their clothing was rotting and disintegrating in the humidity, their insect bites were turning into open, festering sores, and with each passing day it seemed increasingly evident that nobody was coming back for them. They were notching a stick to count the days, but after a while, they were no longer certain just how much time had passed. Had they remembered to cut a notch the day before? They could not be quite sure, for the days merged one into another. In their confusion, they would add another notch to their stick, and in this manner—as later became clear—they became too quick with their calendar. As a result, sooner than they should have, they lost all

“confidence that help would come.”

By their count, that moment of total despair arrived

“five and twenty days” after the others had left. Rocha had promised that he would return in two weeks, three weeks at most, and yet their calendar

stood at November 28. They remembered too that he had taken all his things with him. Their food supplies were nearly gone—clearly, they could not stay on the sandbar much longer. Faced with such facts, Isabel and her two brothers made a fateful decision: They would build a raft. They had both a machete and an ax, and fighting now for their lives, they entered the jungle, hacking away at the few slender trees they could find and dragging them to the sandbar. After cutting the poles to the same length, they lashed them together with lianas. This fragile craft would have to carry them more than ninety miles to safety.

The raft, however, was not big enough to take everyone. Again, they decided to split up. Isabel, her two brothers, and her nephew Martín would go ahead, while Rocha’s slave Antonio would stay behind with Isabel’s two maids, Juanita and Tomasa. The two girls were only eight or nine years old, and Antonio would watch over them, with the hope that a rescue party would soon arrive. Either

Rocha and Joaquín would finally return, or Isabel and the others would make it safely to Andoas and send a canoe back upriver.

Neither option—staying or going—had much to recommend it. This was a plan born of utter desperation and perhaps delirium. Everyone had grown weak and confused on the beach, and things quickly went awry. No sooner had Isabel and the others clambered onto the raft than it began swirling out of control in the river, Juan and Antonio struggling desperately with their two long poles to keep it headed in the right direction. Then disaster struck: “The raft,” as Jean would later write,

“badly framed, struck against the branch of a sunken tree, and overset, and their effects perished in the waves, the whole party being plunged into the water.”

This time, there was no overturned canoe to grab onto. Isabel, still in her heavy dress, gulped for air and went under, her arms flailing as she struggled to keep from drowning. Those who had been left behind on the beach were screaming, helpless to do anything. Then Isabel felt a hand grab the back of her dress, pulling her momentarily to the surface. A burst of air flew into her lungs, then she plunged once more beneath the water, into a tangle of branches and debris. Her mind exploded in panic until yet again she felt a hand reaching for her, pulling her up and toward the bank.

“No one was drowned,” Jean wrote, “Madame Godin being saved, after twice sinking, by her brothers.”

Frightened and muddy, they made their way back to the sandbar. The provisions they had placed aboard the raft were gone, putting them “in a situation still more distressing than before.” Although the wise decision surely would have been to resume waiting there, they felt they had to do something. “Collectively,” they

“resolved on tracing the course of the river along its banks.” Isabel, her two brothers, and Martín would try to walk to Andoas. Antonio, Juanita, and Tomasa would once again stay behind, and if rescue of any kind happened by—perhaps a Quechua Indian would come downriver, or perhaps a search party from Andoas would indeed at last be sent—they could tell it to look for Isabel and her brothers, who planned to stay close to the river’s edge.

In preparation of the long trek ahead, Isabel changed out of her dress and into an extra pair of her brother’s pants. Even in that desperate hour, the sight of Isabel wearing a pair of men’s pants was startling: No one had ever seen a woman so dressed. They packed up the ax, the machete, and a portion of the remaining provisions. Their supplies were so low that they would only have enough food for a few days, and then they would have to forage for something to eat. Their minds were set, and without any further hesitation, Isabel, her two brothers, and Martín—all of them already weak and exhausted—plunged into the jungle.

H

AD

I

SABEL AND HER BROTHERS

possessed a map and a compass, along with supplies, it would have been feasible for them to walk to Andoas. They would have needed to walk away from the river, out of its swampy environs to slightly higher and drier land, and then make a beeline to Andoas, which was about seventy-five miles away as the crow flies. But their plan to follow the river—something that only a mountain-dweller would think of trying—was doomed to fail. The lower Bobonaza twists and turns as it makes its way across this lowland, heading north one moment and south the next, the river carving out huge, slow oxbows, such that one could walk several miles along its banks and end up only a few hundred yards further to the east. Even worse, the vegetation was so thick that they had to hack through it with their machete, which wore them out and slowed their progress. “The banks of the river are beset with trees, undergrowth, herbage, and lianas, and it is often necessary to cut one’s way,” Jean Godin wrote. “By keeping along the river’s side, they found its sinuosities greatly lengthened their way, to avoid which inconvenience they penetrated the wood.”

Although they were now out of the swampiest areas, they found it impossible to orient themselves in the darkened rain forest. The thick canopy of trees filtered out most of the light. They could not see more than twenty or thirty feet in any direction, the landscape a

chaotic mix of shadows and otherworldly shapes. Many of the trees rose from a tangle of aboveground roots, as though they were ready to begin walking around on stilts. Vines and creepers were everywhere, climbing up tree trunks and dripping from the canopy. Even the palm trees had whorls of sharpened spikes around their trunks, a form of armor in this fierce landscape. This gloomy, foreign place was the very world that haunted their imaginations—this was where they had “lost themselves”—and every night, as dusk fell, mosquitoes, flies, and other insects came out in droves, tormenting them in a most physical way.

A nineteenth-century illustration of a primeval forest in the Amazon.

Private collection/Bridgeman Art Library

.

Nineteenth-century explorers who spent any length of time in this type of Amazonian terrain—wet jungle away from the confines of a river—inevitably complained of how utterly intolerable it was. When Spruce explored the forest bordering the Pastaza, in the area around Andoas, he could bear it only for a few hours.

“The very air my be said to be alive with mosquitoes. … I constantly

returned from my walk with my hands, feet, neck and face covered with blood, and I found I could nowhere escape these pests.” Similarly, Humboldt, while traveling through landscape of this kind in the early 1800s, reported that the insects could drive one mad:

Without interruption, at every instant of life, you may be tormented by insects flying in the air. … However accustomed you may be to endure pain without complaint, however lively an interest you may take in the objects of your researches, it is impossible not to be constantly disturbed by the moschettoes,

zancudoes, jejens

, and

tempraneroes

, that cover the face and hands, pierce the clothes with their long sucker in the form of a needle, and, getting into the mouth and nostrils, set you coughing and sneezing whenever you attempt to speak in the open air.

As pervasive as the flying insects can be, the insects that march on the forest floor—the many species of ants—are even more so, their vast numbers sustained by the voluminous leaf litter. Ants are so numerous in a lowland rain forest that collectively they may outweigh all the vertebrates inhabiting it. As the American biologist Adrian Forsyth found, ants in this environment never leave a person alone:

No matter where you step, no matter where you lean, no matter where you sit, you will encounter ants. There are ant nests in the ground, ant nests in the bushes, ant nests in the trees; whenever you disturb their ubiquitous nests, the inhabitants rush forth to defend their homes.

One of the most painful nonlethal experiences a person can endure is the sting of the giant ant

Paraponera clavata

. These ants, with their glistening black bodies over an inch long, sport massive hypodermic syringes and large venom reservoirs. They call on these weapons with wild abandon when provoked, and they are easily offended beasts.

The catalog of bothersome insects in a lowland rain forest is endless. There are giant stinging ants, ants that bite, and ants that both bite and sting. People who have been attacked by the notorious “fire ants” describe the pain as exactly like

“reaching into a flame.” The sting from one of Forsyth’s “bullet ants” is said to be like a “red-hot spike” that produces hours of

“burning, blinding pain.” Colonies of wasps and bees abound, and there are many scorpions and tarantulas. Chiggers fasten onto the legs of passersby who brush against the vegetation, and their saliva contains a digestive enzyme that dissolves the surrounding flesh, producing, as one traveler wrote,

“raging complex itches that come and go for days on end.” The assassin bug is a nasty bloodsucker that bites people around the mouth or on the cheek (and thus is sometimes known as the kissing bug), and even caterpillars in his lowland forest can be menacing. Many, the naturalist John Kricher writes,

“are covered with sharp hairs that cause itching, burning and welts if they prick the skin, a reaction similar to that caused by stinging nettle.”