The Modern Middle East (71 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

The political liberalizations of the 1980s and 1990s, and the economic difficulties that precipitated many of these changes, slowly chipped away at the powers of the Middle Eastern states, eventually leading to the uprisings of 2011. However, in the decades preceding the Arab Spring, neither the semiformal sector nor others socially positioned to articulate popular demands—such as the educated elites, the clergy, and technocratic professionals—witnessed

meaningful rises in their level of influence on state matters. The experiences of the decades leading up to the Arab Spring left almost all Middle Eastern states weaker than before and in need of new justifications, new slogans, and even new institutional devices. But the substance of “new” political formulas differed little from the old. If anything, preoccupation just with surviving and weathering internal political and economic contradictions made the state even less meaningfully attentive to, and even more disconnected from, various social actors.

The informal and semiformal sectors have been divorced from and largely untouched by the political and economic machinations of the state. Neither of these sectors had much to do with the state’s formal institutions or procedures to begin with, and the cosmetic institutional changes of the past decade have done little to change things. Even more substantive changes have not in any meaningful way involved either of these two sectors politically. The formal sector has received the bulk of the state’s attention, and the state has tried the hardest to placate its members, especially the wealthier and more influential ones.

81

Factory owners and other industrialists, members of the bureaucracy, and professionals such as engineers and physicians, along with clerics and intellectuals, have been the main targets of the state’s attempts at making itself more presentable. But the basic economic disconnect between the state and the informal and semiformal sectors of the economy persists. By and large, the economic lives of these two sectors go on as if the political dramas of the past few years had not occurred at all. The merchants of the

suq

(bazaar) still sell their wares or services free of most state regulations, and, as always, those in the informal sector simply struggle to make a living.

The semiformal and informal sectors’ “exit” from interactions with the state can have consequences that go beyond economics. Not only do state agendas become harder to implement, but society’s own abilities to mobilize around political goals become somewhat compromised. By virtue of their cultural dispositions and their social status, members of the semiformal sector are likely to harbor politically oppositional sentiments. By the same token, however, when the general political environment is conducive to earning high profits, they have no reason to engage in overtly oppositional activities. Thus the autonomy that the semiformal sector enjoys from the state does not automatically make it a natural agent for demands for political change or accountability. In the final analysis, the semiformal sector is a commercial class that is likely to put its economic interests above political ideals. Even more likely to do this are members of the informal sector, for whom earning a livelihood is a matter of survival. It is little

wonder, then, that despite highly adverse economic conditions throughout the Middle East in recent years, political activism in both the semiformal and informal sectors has at best been episodic and rare.

On the basis of the analysis presented so far, it should come as no surprise that the Middle East and North Africa lag behind most other parts of the world when it comes to globalization. “Globalization” itself is a contested phenomenon, and there is no universal agreement over its precise meaning or its consequences.

82

For the purposes of this discussion, I focus on the economic aspects of globalization. Globalization is seen here as the substantive integration of national economies into international and global economic forces, and the establishment of multidimensional linkages between them. Broadly, globalization entails the global expansion of capitalism, whereby capitalist economic dynamics traverse national political borders, thus creating institutional and financial linkages and interdependencies between national economies and international economic forces. One frequently used index for measuring economic globalization is the level of foreign direct investment (FDI) into the national economy.

83

While attracting FDI might be a viable mechanism for fostering national economic development, by itself it is not a sufficient indication of levels of economic globalization. Globalization requires the existence of sufficient institutional and infrastructural depth (such as politically independent banks and other financial institutions, investment mechanisms, and manufactured exports) to allow for a national economy’s integration and active participation into the global markets, rather than its mere penetration by powerful and resource-rich multinational corporations. This distinction becomes particularly relevant in relation to the Middle East, where in specific sectors of the economy—such as the automobile and petroleum industries—there may be high levels of FDI while overall levels of economic globalization continue to remain comparatively low.

Globalization’s economically derived linkages do not develop in a vacuum and are bound to have manifold and often far-reaching political and cultural consequences. Given the pervasive patterns of political development and legitimacy across the Middle East, it is precisely these political and cultural dimensions of globalization that have proved most problematic for the region’s states. Not surprisingly, most states of the Middle East have at best an uneasy and unsettled posture toward globalization, welcoming some of its benefits while fiercely seeking to fend off some of its other aspects.

Figure 39.

Skyscrapers of Sheikh Zayed Road, Dubai, at night. Corbis.

In the remaining pages of this chapter, I will focus on two specific aspects of globalization insofar as it relates to the Middle East. First, I will empirically demonstrate that compared to most other regions of the world, the Middle East has experienced relatively low, or at best uneven, levels of globalization. Although in certain instances FDI levels may be high by global standards, overall indices of economic globalization in the Middle East remain low. Second, I will explore the economic and political reasons that underlie the uneasy relationship between most states in the Middle East and globalization, analyzing why some states in the region are more welcoming toward globalization, while others keep it at arm’s length, and still others fiercely fight it on every front. Throughout, the analysis is informed by a theme introduced earlier, namely, that insofar as the region’s political economy is concerned,

political

forces and considerations all too frequently trump the influence and significance of economic ones.

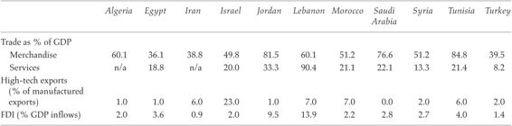

Insofar as net inflows of FDI are concerned, the Middle East has consistently ranked near the bottom in comparison to other regions of the world, followed only by South Asia (table 8).

84

Similarly, as table 8 further demonstrates, the countries of the Middle East rank at the bottom of the global scale when it comes to another key index of economic globalization, namely, the volume of high-technology exports as a percentage of total manufactured exports.

85

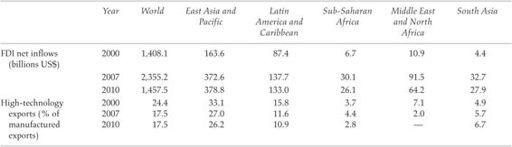

In fact, the Middle East as a whole tends to be one of the world’s top importers and bottom exporters of manufactured goods

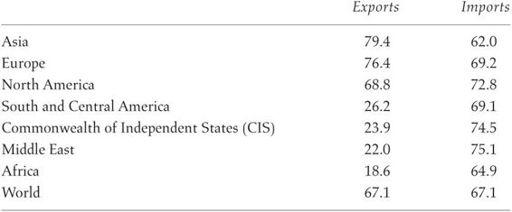

(table 9). Within the region, although trade in merchandise far outweighs trade in services almost everywhere except in Lebanon—whose small economic base and concentration of wealth among a narrow elite have spurned the growth of the services industry—only a small percentage of manufactured exports tend to be high-technology goods. Moreover, across the region FDI as a percentage of the gross domestic product remains very low (table 10). This is further supported by the available data for the region’s Arab countries, for whom, unsurprisingly, petroleum is the biggest export, while manufactured goods, especially machinery and transportation equipment are the biggest imports (table 11).

Table 8.

Global Levels of Foreign Direct Investment

SOURCE:

World Bank, Development Indicators Database, “Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows” and “High-Technology Exports (% of Manufactured Exports,” under “Data,” “Indicators,”

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator

.

Table 9.

Share of Manufactures in Total Merchandise Trade by Region, 2010 (%)

SOURCE:

World Trade Organization,

International Trade Statistics

, 2011 (Washington, DC: World Trade Organization, 2011), p. 61.

Another key index of economic globalization is intraregional trade and the establishment of economic linkages among regional trading partners. In many ways, regional economic integration is both a by-product and a smaller scale of globalization, expanding markets and transportation networks, enhancing investment and trade opportunities, facilitating labor mobility, and deepening linkages between local enterprises and those abroad. The European Union and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) represent two of the world’s largest regional trading partnerships, with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the Mercado Comun del Sur (MERCOSUR) having also made significant strides toward fostering regional economic linkages and integration in Southeast Asia and South America, respectively.

86

In the Middle East or even only its Arab subregion, however, discernible patterns of regional economic or trade

linkages have yet to emerge. In fact, as table 12 demonstrates, overall, the Arab countries tend to trade less with each other than with other regions of the world. From 2006 to 2010, only 9.1 percent of exports and 12.4 percent of imports by Arab countries were the result of intra-Arab trade. The Middle East has yet to witness meaningful regional economic integration.

Table 10.

Trade Indicators in Selected Middle Eastern Countries, 2009