The Modern Middle East (72 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

SOURCE:

World Bank,

World Development Indicators, 2011

(Washington, DC: World Bank, 2011).

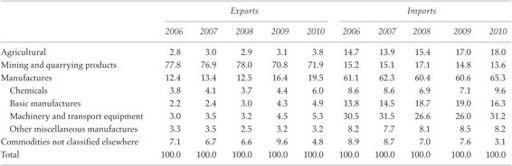

Table 11.

Commodity Structure of Arab International Trade, 2006–10 (%)

SOURCE:

Arab Monetary Fund,

The Joint Arab Economic Report, 2011

(Abu Dhabi: Arab Monetary Fund, 2011), p. 125.

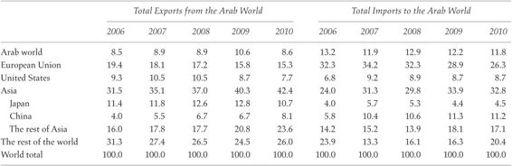

Table 12.

Arab World Trade Partners, 2006–10 (direction of foreign trade of Arab states)

SOURCE:

Arab Monetary Fund,

The Joint Arab Economic Report, 2011

(Abu Dhabi: Arab Monetary Fund, 2011), p. 124.

Such low levels of regional integration are not for lack of trying, nor, in fact, have they always been the case. World War II, for example, saw increased levels of intraregional trade, largely because the Middle East was used so extensively by the United States and Britain as a supply route to the Soviet Union.

87

Beginning in the late 1950s there was an attempt to establish an Arab Common Market, although the effort was abandoned in the mid-1960s as a combined result of internal political bickering and the advent of the Nasserist state across the region. By the end of the 1980s, with the region more divided than before, rhetorical declarations and promises of increased intraregional trade flew in the face of mutual mistrust and bitter acrimonies.

88

Hopes for increased regional integration were once again rekindled in the 1990s with three major developments: the signing of the Oslo Accords and the promises of peace and economic trade with Israel that it entailed; the unveiling of the Euro-Mediterranean Association’s agreement to establish a free-trade area in manufactured goods between a number of European and Arab countries by 2010; and, after much delay, substantive moves by the states of the Gulf Cooperation Council to give meaning to their promises of monetary and economic union.

89

As the statistical evidence presented above indicates, such hopes have yet to come to fruition.

There are several key reasons for the comparatively low levels of economic globalization—and, correspondingly, regionalization—in the Middle East. Mention has already been made of the stunted growth of institutional and structural mechanisms across the Middle East that would help facilitate the expansion of modern global capitalism into the region. Chief among these would be a politically independent and transparent banking system, which economists argue is central to fostering growth and development.

90

Central banks, one of whose main responsibilities is to set monetary and fiscal policy, play an especially elemental role in this regard. There are, however, literally no central banks across the Middle East that would qualify as politically independent, with the ineffectual central bank of the Palestinian National Authority, at least on paper, being an exception.

91

Other structural factors that slow the pace of globalization in the Middle East include the continued presence of the state in the national economy, despite economic liberalization moves designed to curtail the intrusiveness

of state institutions, as well as the state’s own inability to create an attractive and transparent regulatory environment that would foster deeper linkages between the local and the international economies.

92

Related to structural constraints on globalization are political and diplomatic ones, with a number of Middle Eastern countries either proving too unstable and inhospitable for foreign investments or being subject to stringent international economic sanctions, or both. For much of the past thirty years or so, for example, both Iran and Iraq have been either at war with each other or locked in a cold war with the West and under sanctions, the end result being their increasing isolation from the world economy. For different reasons and under different circumstances, Syria, Libya, and Sudan—as well as Algeria during its civil war in the 1990s—have also either been under international trade sanctions or otherwise been too unstable politically to meaningfully engage with the global economy.

Equally important is the political management of the cultural dimensions of economic globalization. By revolutionizing information technology and facilitating easier access to means of communication across the globe, globalization can be just as consequential—at times, in fact, far more consequential—in the spreading and diffusion of cultural values as it is in bringing about economic linkages and interactions. As chapters 7 and 8 demonstrate, a number of states in the Middle East take very deliberate, and often guarded, postures in relation to the diffusion into their societies of norms and values from abroad, frequently viewing them as inimical to the cultural milieu that they seek to create and on which their legitimacy is built. The culturally conservative states in Iran and Saudi Arabia are two extreme examples of states fearing the cultural consequences of globalization. While perhaps not as directly frightened as state leaders in Tehran and Riyadh, most political elites elsewhere in the Middle East tend to be apprehensive about possible responses and reactions by the various groups in their societies to globalization’s cultural dimensions. It should be remembered that “Westernization” is not the only side effect of globalization. With the spread of the Internet and the rise of multiple satellite television channels beaming out of many Middle Eastern capitals, a phenomenon pioneered by Al-Jazeera, “Islamization” and the appearance of “global muftis” can be considered just as much products of globalization.

93

The attempted cherry-picking by political leaders of which aspects of globalization to embrace and which ones to fend off, or how tightly to control a process that by nature does not lend itself to control, largely accounts for its uneven and halting spread across the Middle East.

Finally, perhaps the most important factor hindering the pace and depth of economic globalization in the Middle East has to do with the different

conceptions of nationalism that state elites have adopted across the region as it pertains to their political legitimacy. As chapters 3 and 4 demonstrated, nationalism remains a potent force throughout the region, and one that is frequently employed for purposes of political mobilization or legitimacy. How this nationalism is articulated and conceptualized by the political elite is key in shaping a larger national context that might prove hospitable or inimical to economic globalization. If nationalism is presented by the elite as ownership and control over national resources, and is in turn generally accepted by the public to have such a meaning, then the prospects for economic globalization, which entails investments by and interactions with foreign capital, are extremely bleak. This is the nationalism that was so loudly proclaimed by Nasser and that resonates to this day in the far corners of the Middle East. It is a nationalism at the center of which rests the notion that the nation’s resources belong to none other than the nation itself, and that consequently their development and marketing cannot be realized through reliance on foreign capital and expertise.

If, however, nationalism is presented not so much as control over the process for developing domestic resources but rather as ownership over the outcome of such development, then the larger national context is more amenable to economic globalization. Throughout the small, politically conservative oil monarchies of the Persian Gulf, especially Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE, as well as in Turkey and Israel, this is the perception of nationalism that has been articulated by the political elites and has been largely accepted by the public. In the oil monarchies, policy makers have been painfully aware of their societies’ demographic and technological limitations. Even if they wanted to, they could not possibly manage the exploitation of their vast oil resources on their own and must instead rely on Western multinational corporations to extract and export the very oil that brought them fabulous riches. With rentierism underwriting the political bargain, this emerging conception of nationalism quickly began revolving around the state’s management of the oil wealth—that is, the creation of cradle-to-grave welfare states—rather than its heroic struggle against the insidious devices of imperialism. Today, completely different conceptions of nationalism exist on the northern shores of the Persian Gulf, in Iran, as compared to its southern shores, where the gleaming cities of Manama, Doha, Abu Dhabi, and Dubai would not have existed in their current forms had it not been for the pervasive presence of multinational corporations.

Both on a regional scale and globally, economic integration with the outside world has largely eluded the countries of the Middle East, except

perhaps the handful of small states in the Arabian peninsula. Across the Middle East, regional integration has lagged because of mutual mistrust and lack of commitment and political will by state leaders to foster meaningful means of economic linkage across national borders. At the same time, the overwhelming majority of Middle Eastern economies lack the institutional capacities and expertise needed to partake in global economic activities on an equal footing with their European and Asian counterparts, thus being forced, almost by default, to be on the receiving end of globalization rather than active participants. The deep-seated skepticism of many local policy makers concerning the larger phenomenon of globalization has only reinforced its comparatively low penetration into the Middle East. Not surprisingly, then, the region lags behind on most indices of economic globalization.

This chapter has highlighted four aspects of the political economy of the Middle East: pervasive statism; unruly rentierism; the state’s uneven control over and penetration of the different sectors of the economy; and halting and at best uneven levels of globalization. The combined consequence of these phenomena has been a political economy that has historically supported and sustained authoritarianism. Each phenomenon, in fact, has a self-perpetuating logic and has so far managed to resist serious changes or reforms. How the Arab Spring, and more importantly the sense of popular empowerment of the urban middle classes that it entailed, will challenge the political economy of authoritarianism in the Middle East remains to be seen. But so long as the basis of the political economy remains unchanged in much of the Middle East, authoritarianism remains a threat.

Beginning in the 1920s and 1930s in Turkey and Iran, respectively, and then in the 1950s in the rest of the region, the state in the Middle East assumed a direct role in owning and controlling, or at the very least extensively regulating, the various forces and means of production. In one shape or another, economic patronage became the preferred modus operandi of patron states across the region. The assumption was also that the state was in the best position to decide on and implement the most prudent course of economic development. But the state’s assumption of numerous developmental tasks, and its proportional growth in size in the process, masked a more fundamental institutional weakness. This weakness derived from the state’s need to consolidate its powers through incorporating the popular classes and catering to many of their demands. The state, in other words, secured its hold over power by placating the popular classes and subsequently found itself beholden to them. What ensued was an undisciplined,

unruly rentierism, one that has kept the developmental potentials of the region in check.

At the same time, a negative equilibrium of sorts developed between a state that was not quite able to implement many of its economic agendas and a society whose economically autonomous actors, in the form of the semiformal sector, are only partially able to evade the regulatory reach of the state. The state, of course, is far from irrelevant. Its orchestration of the national macroeconomy still influences the lives of all citizens, rich and poor, irrespective of the economic sector to which they belong. The noneconomic initiatives of the state—conscription, policies toward ethnic or religious minorities, state-sponsored gender equity or discrimination initiatives, and compulsory education laws, to mention only a few—can be just as profoundly consequential for the lives of the citizenry. But in terms of routine economic interactions between the state and those outside the formal sector, the prevailing pattern of relationship is one of disconnection. State control over social actors, their resources, and their activities is neither as direct nor as complete as state actors would like. Nevertheless, it is sufficient for state actors to continue holding on to power and, if they so choose, to maintain the status quo seemingly indefinitely.