The Modern Middle East (73 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

On the whole, despite crises and changes, the political economy of the Middle East has not helped society become empowered and/or autonomous in relation to the state. Even within the context of the post–Arab Spring era, we have in the Middle East states whose development potentials are curtailed by the tangled webs they themselves have woven, presiding over societies whose ability to mount autonomous action in relation to the state—whether in opposition to the state or even in its support—is severely curtailed by various bureaucratic and police institutions. But the bonds of patronage are not nearly robust enough in most countries of the region to maintain ruling bargains indefinitely, particularly in places where rentier arrangements are indirect and weak. In only a handful of Middle Eastern countries, most notably the oil monarchies on the shores of the Persian Gulf, are financial and economic resources sufficient to transfer rent incomes directly into the pockets of the citizenry (in the form of entitlements and cash handouts), and even then a large state like Saudi Arabia has not had complete success. In most other countries, rentierism manifests itself in indirect forms, as in state employment and price subsidies, and there is little that binds the population to the state in direct ways. But dependence on state-supplied paychecks, coupled with a weak private sector, has been enough to undermine the potential for autonomous action and organization on the part of social actors. As the fateful events of 2011 demonstrated, however,

politically motivated mass mobilization can indeed occur, especially when cracks in the state-imposed wall of fear make social actors feel empowered and when the ruling coalition loses some of its cohesion and unity. These two ingredients—social actors’ empowerment and cracks within the ruling coalition—are rare, and their simultaneous occurrence is even less common. Whether the examples of Tunisia and Egypt can be replicated elsewhere in the region, and whether the Arab Spring’s early pioneers and other countries in the Middle East can become democratic, remains far from clear at this point.

11

Challenges Facing the Middle East

The political history of the Middle East has been fraught with turmoil and political instability. By the middle of the twentieth century, most of the region had experienced two separate, qualitatively different periods of colonial subjugation. First came Ottoman rule, from the early to mid-1500s up until the late 1910s, and then British and French rule, beginning with the end of the First World War and lasting until the late 1940s. Not surprisingly, the state-building processes of the 1940s and 1950s—like those in Turkey in the 1920s and in Iran in the 1930s—took on an urgent and feverish character. A similar sense of urgency characterized the modernization drive of the 1960s and 1970s. Dictatorships were established, overthrown, and reestablished; wars were fought, lost, and refought; a new state was born and another died; and the wretched history of one diaspora came to an end but the misery of another got under way. The past four decades have brought more of the same, though with slightly different features and added layers of complexity.

Not every aspect of Middle Eastern history has been cyclical. In the 1960s and 1970s, the physical character of the Middle East changed tremendously. Cities were expanded, massive monuments, roads, and factories were built, and the march toward “development” yielded some tangible results. The region’s countless monarchs—both official ones and the others who chose to label themselves “president”—could point to their countries’ economic and industrial progress with a measure of justified pride. By the late 2010s, hopeful spring swept across much of the region. Cairo’s modern-day pharaoh, Hosni Mubarak, fell from power and was taken to court. Tunisia’s Ben Ali fled and took refuge in Saudi Arabia. Qaddafi, who fancied himself as the King of All Africa, was dragged out of a sewer pipe and shot. And Bashar Assad, once seemingly invincible, desperately hung on to power. The Middle East’s remaining dictators were put on notice.

But many in the Middle East remained poor, and the fruits of industrial development were not shared evenly anywhere. More fundamentally, as the United Nations has pointed out, much of the Middle East, especially the Arab world and Iran, continues to suffer from three glaring deficits—in freedom, in women’s empowerment, and in human capabilities and knowledge relative to income.

1

Nevertheless, industrial development became less of a dream and more of a reality throughout the Middle East in the twentieth century. What differed greatly was its depth compared to that in other parts of the world and the different levels to which it spread in the various parts of the region.

Industrial development, uneven as it has been, has had several adverse side effects with which the countries of the Middle East must now contend. For the past century or so, the challenges facing the Middle East have been those of state building, military security, political consolidation, and economic development. Far from being resolved or somehow withering away, these challenges are now being compounded by the negative consequences of industrial modernization. Of these, three seem particularly pressing: astoundingly high rates of population growth; the increasing scarcity of water resources; and the pollution of various environmental resources, especially air. This chapter examines the magnitude of each of these problems and highlights the negative consequences each has had so far for the countries of the Middle East. These are the defining challenges that the Middle East must confront in the twenty-first century. Failure to resolve them could well end up being more consequential than the wars and revolutions that became such hallmarks of the past hundred years.

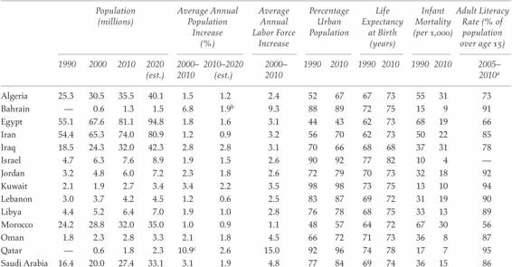

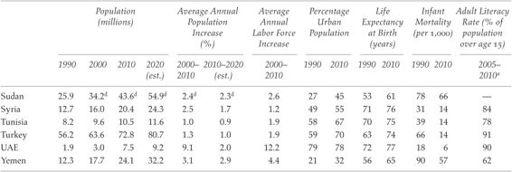

With a few exceptions in sub-Saharan Africa, the countries of the Middle East tend to have the highest rates of population growth in the world (table 13). Overall, according to the World Bank, between 1998 and 2015 the population of the Middle East is expected to grow at an average rate of 2.0 percent annually, compared to 2.1 percent for sub-Saharan Africa, 1.2 percent for East and South Asia and the Pacific, and 1.3 percent for South America.

2

Tragically, in sub-Saharan Africa, infant mortality rates are much higher than in the Middle East (89 per 1,000 live births compared to 32 in the Middle East in 2007) and life expectancy much lower (fifty-one years in Africa compared to seventy in the Middle East in 2007). As a result, the slightly higher annual rates of population growth in Africa are offset by higher levels of infant mortality and shorter life spans. At current rates, the population of the Middle East is estimated to double in approximately twenty-seven years.

3

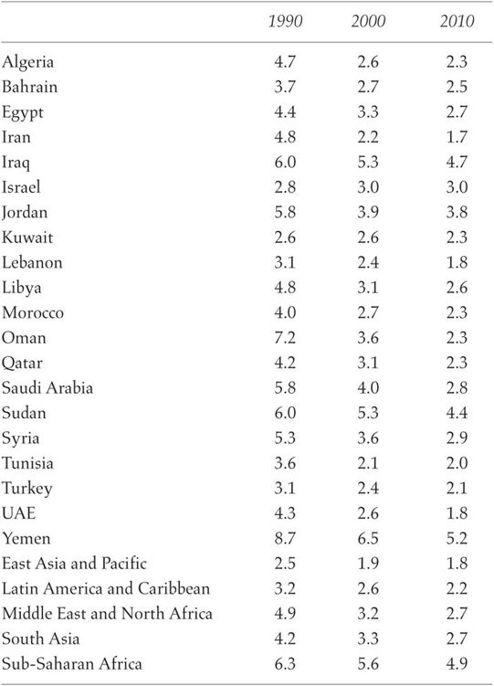

As with the rest of the developing world, population growth rates in the Middle East accelerated beginning especially in the 1950s and 1960s, when advances in medical technology and hygiene resulted in declining levels of infant mortality and longer life expectancy. In specific relation to the Middle East, two additional factors account for the region’s high rate of population growth. The first has to do with the relatively high rates of fertility among Middle Eastern women as compared to women elsewhere. In 1990, women in the Middle East on average had 4.9 children, a figure that dropped to 3.2 a decade later and to 2.7 in 2010 (table 14). By contrast, fertility rates were lower in all other regions of the developing world except sub-Saharan Africa.

Fertility rates tend to be higher in sub-Saharan Africa because of pervasive insecurity and fears about the future, in turn prompting parents to procreate for posterity’s sake. In the Middle East, high fertility rates tend to be a product of factors that are mostly cultural rather than economic. Women in the Middle East and in other Islamic countries tend to get married at a much younger age. Overall, the prevalence of teenage brides tends to be higher in Muslim countries as compared to other parts of the developing world. Although cultural norms regarding marriage appear to be changing, women in the Middle East are likely to get pregnant earlier and more frequently. Early marriages are encouraged by social and cultural values that attach high esteem to the institution of the family and uphold the virtues of motherhood.

4

For many parents, especially those from more traditional backgrounds, there is also the fear that their daughter, if not quickly married off, may engage in premarital sex and bring dishonor to herself and her family.

5

Although not unique to the region, greater prestige attached to having male children also accounts for high fertility rates in the Middle East. Male offspring are often seen as carriers of the family name and tradition, as well as protectors of parents in old age and in times of need. They are, in essence, guarantors of the continuance of the family in the uncertain world of the future. Most parents, therefore, continue having children until they have produced the number of boys that they consider sufficient.

The low availability and use of contraceptives also account for the high rate of fertility among women in the Middle East. According to most interpretations of the

sharia

(Islamic law), Islam does not prohibit the use of contraceptives as such, and couples are able to exercise some control over reproduction.

6

This does not extend to abortion, however, which as a method of birth control is legally banned in almost all countries of the Middle East.

7

Nevertheless, despite a general lack of religious prohibitions on the use of contraceptives, married women in the Middle East are half as

likely as women elsewhere in the developing world to be using some form of birth control: 22 percent in the Middle East as compared to 54 percent in other developing countries.

8

Statistics published by the World Bank in 2007 place the average prevalence of contraceptives among women in the Middle East and North Africa, married and unmarried alike, at 39.0 percent, compared

to 41.4 percent in Asia and the Pacific and 49.4 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean.

9

Again, most of the reasons for avoiding contraception appear to be cultural: men do not like using them, and, given that sex as a subject remains taboo and sex education tends to be nonexistent, most couples depend on natural, unreliable methods of contraception (such as withdrawal).

10

Table 13.

Population Characteristics in the Middle East

SOURCE:

World Bank,

World Development Indicators

, 2012 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2012), pp. 42–44, 46–48, 94–96, 128–30, 186–88; World Bank, World Development Indicator Database, “Population, Total,” “Population Growth (Annual %),” “Labor Force, Total” (used to calculate annual labor force increase), “Urban Population (% of Total),” “Life Expectancy at Birth, Total,” “Mortality Rate, Infant,” and “Literacy Rate, Adult Total,” under “Data,” “Indicators,”

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator

.

a

Data are for the most recent year available.

b

Figure is for 2007.

c

Increase is due to a surge in the number of migrants since 2004.

d

Includes South Sudan.

Table 14.

Fertility Rates in the Middle East as Compared to Other World Regions (births per woman)