The Monkey Grammarian (10 page)

A Monkey of Galta (photograph by Eusebio Rojas)

Asymmetry between the two parts: above, copulation between males and females of the same species; below, copulation of a human female with males of various species of animals and with another human female—never with a human male. Why? Repetition, analogy, exception. On the expanse of motionless space—wall, sky, page, sacred pool, garden—all these figures intertwine, trace the same sign and appear to be saying the same thing, but what is it that they are saying?

I halted before a fountain standing in the middle of the street, in the center of a semicircle. The tiny little stream of water flowing from the faucet had made a mud puddle on the ground; a dog with sparse, dark gray fur and patches of raw, bruised flesh was licking at it. (The dog, the street, the puddle: the light of three o’clock in the afternoon, a long time ago, on the cobblestones of a narrow street in a town in the Valley of Mexico, the body of a peasant dressed in white cotton work clothes lying in a pool of blood, the dog that is licking at it, the screams of the women in dark skirts and purple shawls running in the direction of the dead man.) Amid the almost completely ruined buildings forming the semicircle around the fountain was one that was still standing, a massive, squat structure with its heavy doors flung wide open: the temple. From where I was standing its inner courtyard could be seen, a vast quadrangle paved with flagstones (it had just been washed down and was giving off a whitish vapor). Around the edges of it, against the wall and underneath a roof supported by irregularly shaped pillars, some of stone and others of masonrywork, all of them whitewashed and decorated with red and blue designs, Grecian frets, and bunches of flowers, stood the altars with the gods, separated from each other by wooden bars, as though they were cages. At the entrances were various booths where elderly vendors were peddling their wares to the crowd of worshipers: flowers, sticks and bars of incense; images and color photographs of the gods (depicted by movie actors and actresses) and of Gandhi, Bose, and other heroes and saints;

I halted before a fountain standing in the middle of the street, in the center of a semicircle. The tiny little stream of water flowing from the faucet had made a mud puddle on the ground; a dog with sparse, dark gray fur and patches of raw, bruised flesh was licking at it. (The dog, the street, the puddle: the light of three o’clock in the afternoon, a long time ago, on the cobblestones of a narrow street in a town in the Valley of Mexico, the body of a peasant dressed in white cotton work clothes lying in a pool of blood, the dog that is licking at it, the screams of the women in dark skirts and purple shawls running in the direction of the dead man.) Amid the almost completely ruined buildings forming the semicircle around the fountain was one that was still standing, a massive, squat structure with its heavy doors flung wide open: the temple. From where I was standing its inner courtyard could be seen, a vast quadrangle paved with flagstones (it had just been washed down and was giving off a whitish vapor). Around the edges of it, against the wall and underneath a roof supported by irregularly shaped pillars, some of stone and others of masonrywork, all of them whitewashed and decorated with red and blue designs, Grecian frets, and bunches of flowers, stood the altars with the gods, separated from each other by wooden bars, as though they were cages. At the entrances were various booths where elderly vendors were peddling their wares to the crowd of worshipers: flowers, sticks and bars of incense; images and color photographs of the gods (depicted by movie actors and actresses) and of Gandhi, Bose, and other heroes and saints;

bhasma

, the soft red paste with which the faithful trace religious signs on their foreheads at the moment in the ceremony when offerings are made; fans with advertisements for Coca-Cola and other soft drinks; peacock feathers; stone and metal lingas; boy dolls representing Durga mounted on a lion; mandarin oranges, bananas, sweets, betel and bhang leaves; colored ribbons and talismans; paperbound prayer books, biographies of saints, little pamphlets on astrology and magic; sacks of peanuts for the monkeys…. Two priests appeared at the doors of the temple. They were fat and greasy, naked from the waist up, with the lower part of their bodies draped in a

dhoti

, a length of soft cotton cloth wound between their legs. A Brahman cord hanging down over their breasts, as ample as a wetnurse’s; hair, pitch-black and oiled, braided in a pigtail; soft voices, obsequious gestures. On catching sight of me drifting amid the throng, they approached me and invited me to visit the temple. I declined to do so. At my refusal, they began a long peroration, but without stopping to listen to it, I lost myself in the crowd, allowing the human river to carry me along.

The devout were slowly ascending the steep path. It was a peaceful crowd, at once fervent and good-humored. They were united by a common desire: simply to get to where they were going, to see, to touch. Will and its tensions and contradictions played no part in that impersonal, passive, fluid, flowing desire. Thejoy of total trust: they felt like children in the hands of infinitely powerful and infinitely beneficent forces. The act that they were performing was inscribed upon the calendar of the ages, it was one of the spokes of one of the wheels of the chariot of time. They were walking to the sanctuary as past generations had done and as those to come would do. Walking with their relatives, their neighbors, and their friends and acquaintances, they were also walking with the dead and with those not yet born: the visible multitude was part of an invisible multitude. They were all walking through the centuries by way of the same path, the path that cancels out the distinction between one time and another, and unites the living with the dead. Following this path we leave tomorrow and arrive yesterday: today.

Although some groups were composed only of men or only of women, the majority were made up of entire families, from the great grandparents down to the grandchildren and great grandchildren, and including not only those related by blood but by religion and caste as well. Some were proceeding in pairs: the elderly couples babbled incessantly, but those recently wed walked along without exchanging a word, as though surprised to find themselves side by side. Then there were those walking all by themselves: the beggars with infirmities arousing pity or terror—the hunchbacked and the blind, those stricken with leprosy or elephantiasis or paralysis, those afflicted with pustules or tumors, drooling cretins, monsters eaten away by disease and wasting away from fever and starvation—and the others, erect and arrogant, convulsed with wild laughter or mute and possessed of the bright piercing eyes of illuminati, the s dhus, wandering ascetics covered with nothing but a loincloth or enveloped in a saffron robe, with kinky hair dyed red or scalps shaved bare except for a topknot, their bodies smeared with human ashes or with cow dung, their faces daubed with paint, and carrying in their right hand a rod in the shape of a trident and in their left hand a tin bowl, their only possession in this world, walking alone or accompanied by a young boy, their disciple, and in certain cases their catamite.

dhus, wandering ascetics covered with nothing but a loincloth or enveloped in a saffron robe, with kinky hair dyed red or scalps shaved bare except for a topknot, their bodies smeared with human ashes or with cow dung, their faces daubed with paint, and carrying in their right hand a rod in the shape of a trident and in their left hand a tin bowl, their only possession in this world, walking alone or accompanied by a young boy, their disciple, and in certain cases their catamite.

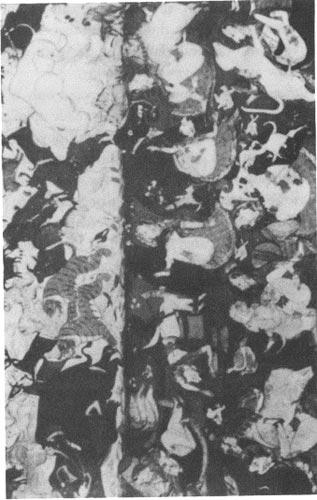

The n yik

yik , the incarnation of the love of all creatures, miniature in an album, Rajasthan, c. 1780.

, the incarnation of the love of all creatures, miniature in an album, Rajasthan, c. 1780.

Little by little we crossed hill and dale, amid ruins and more ruins. Some ran ahead and then lay down to rest beneath the trees or in the hollows of the rocks; the others walked along at a slow, steady pace, without halting; the lame and the crippled dragged themselves painfully along, and the invalids and paralytics were borne on stretchers. Dust, the smell of sweat, spices, trampled flowers, sickly-sweet odors, stinking breaths of air, cool breaths of air. Little portable radios, belonging to bands of young boys, poured forth catchy popular love-songs; small children clinging to their mother’s breasts or skirts wailed and squalled; the devout chanted hymns; there were some who talked among themselves, some who laughed uproariously, and some who wept or talked to themselves—a ceaseless murmur, voices, cries, oaths, exclamations, outcries, millions of syllables that dissolved into a great, incoherent wave of sound, the sound of humans making itself heard above the other sounds of the air and the earth, the screams of the monkeys, the cawing of the crows, the sea-roar of the foliage, the howl of the wind rushing through the gaps in the hills.

The wind does not hear itself but we hear it; animals communicate among themselves but we humans each talk to ourselves and communicate with the dead and with those not yet born. The human clamor is the wind that knows that it is wind, language that knows that it is language and the means whereby the human animal knows that it is alive, and by so knowing, learns to die.

The sound of several hundred men, women, and children walking along and talking: the promiscuous sound of gods, dead ancestors, unborn children and live ones hiding between their mother’s bodice and her breast, with their little copper coins and their talismans, their fear of dying. The wind does not complain: man is the one who hears, in the complaint of the wind, the complaint of time. Men hears himself and looks at himself everywhere: the world is his mirror; the world neither hears us nor looks at itself in us: no one sees us, no one recognizes himself in man. To those hills we were strangers, as were the first men who, millennia ago, first walked among them. But those who were walking with me did not know that: they had done away with distance—time, history, the line that separates man from the world. Their pilgrimage on foot was the immemorial rite of the abolishing of differences. Yet these pilgrims knew something that I did not know: the sound of human syllables was simply one more noise amid the other noises of that afternoon. A different sound, yet one identical to the screams of the monkeys, the cries of the parakeets, and the roar of the wind. To know this was to reconcile oneself with time, to reconcile all times with all other times.