The Monkey Grammarian (9 page)

I feel someone watching me and turn around: the band of monkeys is spying on me from the other end of the terrace. I walk toward them in a straight line, unhurriedly, my stick upraised; my behavior does not seem to make them uneasy, and as I continue to walk toward them, they remain there, scarcely moving, looking at me with their usual irritating curiosity and their no less usual impertinent indifference. As soon as they feel me close by, they leap up, scamper off, and disappear behind the balustrade. I walk over to the opposite edge of the terrace and from there I see in the distance the bony crest of the mountain outlined with cruel precision. Down below, the street and the fountain, the temple and its two priests, the booths and their elderly vendors, the children leaping about and screeching, several starving cows, more monkeys, a lame dog. Everything is radiant: the animals, the people, the trees, the stones, the filth. A soft radiance that has reached an accord with the shadows and their folds. An alliance of brightnesses, a thoughtful restraint: objects take on a secret life, call out to each other, answer each other, they do not move and yet they vibrate, alive with a life that is different from life. A universal pause: I breathe in the air, the acrid odor of burned dung, the smell of incense and poverty. I plant myself firmly in this moment of motionlessness: the hour is a block of pure time.

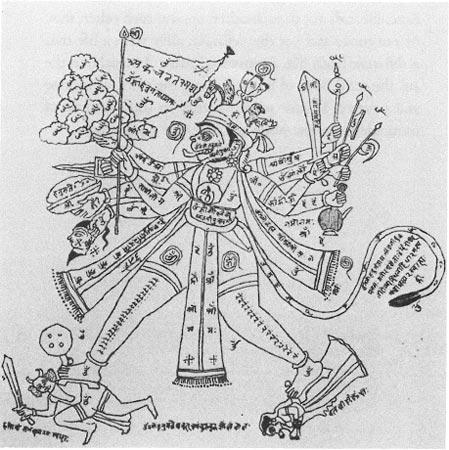

Ten-armed Hanum n, Jodhpur, 19th century.

n, Jodhpur, 19th century.

A thicket of lines, figures, forms, colors: nooses of curving strokes, maelstroms of color in which the eye drowns, a series of intertwined figures, repeated in horizontal bands, that totally confound the mind,

A thicket of lines, figures, forms, colors: nooses of curving strokes, maelstroms of color in which the eye drowns, a series of intertwined figures, repeated in horizontal bands, that totally confound the mind,

I

as though space were being slowly covered line by line, with letters of the alphabet, each one different and yet related to the following one in the same way, and as though all of them, in their various conjunctions, invariably kept producing the same figure, the same word. Nonetheless, in each case the figure (the word) has a different meaning. Different and the same.

Above, the innocent kingdom of animal copulation. A plain covered with sparse, sunscorched grass, strewn with flowers the size of trees and with trees the size of flowers, bounded in the distance by a narrow red-tinged horizon—almost the trace of a scar that is still fresh:, it is dawn or sunset—on which tiny, fuzzy white patches merge or dissolve, vague mosques and palaces that are perhaps clouds. And superimposed on this innocuous landscape, filling it completely with their obsessive, repeated fury, tongue thrust out, gleaming white teeth bared, immense staring eyes, pairs of tigers, rats, camels, elephants, blackbirds, hogs, rabbits, panthers, crows, dogs, donkeys, squirrels, a stallion and a mare, a bull and a cow—the rats as big as elephants, the camels the same size as the squirrels—all coupling, the male mounted atop the female. A universal, ecstatic copulation.

Below: the ground is not yellow or dark gray but a bright parrot-green. Not the earthly kingdom of animals but the meadow-carpet of desire, a brilliant surface dotted with little red, white, and blue flowers, flowers-that-are-stars-that-are-signs (meadow: carpet: zodiac: calligraphy), a motionless garden that is a copy of the fixed night sky that is reflected in the design of the carpet that is transfigured into the pen-strokes of the manuscript. Above: the world in its myriad repetitions; below: the universe is analogy. But it is also exceptions, rupture, irregularity: as in the upper portion, occupying the entire space, outbursts of primal fury, vehement outcries, violent red and white spurts, five in the upper band and four in the lower one, nine enormous flowers, nine planets, nine carnal ideograms: a n yik

yik , always the same one, like the repetition of the same luminous patterns in fireworks displays, emerging nine times from the circle of her skirt, a blue corolla spattered with little red dots or a red corolla strewn with tiny black and blue crosses (the sky as a meadow and both reflected in a woman’s skirt)—a n

, always the same one, like the repetition of the same luminous patterns in fireworks displays, emerging nine times from the circle of her skirt, a blue corolla spattered with little red dots or a red corolla strewn with tiny black and blue crosses (the sky as a meadow and both reflected in a woman’s skirt)—a n yik

yik lying on the carpet-garden-zodiac-calligraphy, reclining on a pillow of signs, her head thrown back and half hidden by a translucent veil through which her jet-black, pomaded hair can be seen, her profile transformed into that of an idol by her heavy ornaments—gold earrings set with rubies, diadems of pearls across the forehead, a diamond nose-pendant, chokers and necklaces of green and blue stones—sparkling rivers of bracelets on the arms, breasts with pointed nipples swelling beneath the orange

lying on the carpet-garden-zodiac-calligraphy, reclining on a pillow of signs, her head thrown back and half hidden by a translucent veil through which her jet-black, pomaded hair can be seen, her profile transformed into that of an idol by her heavy ornaments—gold earrings set with rubies, diadems of pearls across the forehead, a diamond nose-pendant, chokers and necklaces of green and blue stones—sparkling rivers of bracelets on the arms, breasts with pointed nipples swelling beneath the orange

choix

, the body naked from the waist down, the thighs and belly a gleaming white, the shaved pubis a rosy pink, the labia of the vulva standing out, the ankles circled by bracelets with little tinkling bells, the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet tinted red, the upraised legs clasping the partner nine times—and it is always the same n yik

yik , simultaneously possessed nine times in the two bands, five times in the upper one and four in the lower one, by nine lovers: a wild boar, a male goat, a monkey, a stallion, a bull, an elephant, a bear, a royal peacock, and another n

, simultaneously possessed nine times in the two bands, five times in the upper one and four in the lower one, by nine lovers: a wild boar, a male goat, a monkey, a stallion, a bull, an elephant, a bear, a royal peacock, and another n yik

yik —one dressed exactly like her, with the same jewels and ornaments, the same eyes of a bird, the same great noble nose, the same thick, well-defined mouth, the same face, the same plump whiteness—another self mounted atop her, a consoling two-headed creature set like a jewel in the twin vulvas.

—one dressed exactly like her, with the same jewels and ornaments, the same eyes of a bird, the same great noble nose, the same thick, well-defined mouth, the same face, the same plump whiteness—another self mounted atop her, a consoling two-headed creature set like a jewel in the twin vulvas.