The Monkey Grammarian (8 page)

Hanum n devouring the Sun and being followed by Indra. Al-war, Rajasthan.

n devouring the Sun and being followed by Indra. Al-war, Rajasthan.

On the wall the body of the man is a bridge suspended over a motionless river: Splendor’s body. As the crackling of the fire on the hearth diminishes, the shadow of the man kneeling above the young woman increases in size until it covers the entire wall. The conjoining of the shadows precipitates the discharge. Sudden whiteness. An endless fall in a pitch-black cave. Afterwards he discovers himself lying beside her, in a half-shadow on the shore of the world: farther beyond are the other worlds, that of the objects and the pieces of furniture in the room and the other world of the wall, barely illuminated by the faint glow of the dying embers. After a time the man rises to his feet and stirs up the fire. His shadow is enormous and flutters all about the room. He returns to Splendor’s side and watches the reflections of the fire glide over her body. Garments of light, garments of water: her nakedness is more naked. He can now see her and grasp the whole of her. Before he had glimpsed only bits and pieces of her: a thigh, an elbow, the palm of a hand, a foot, a knee, an ear nestling in a lock of damp hair, an eye between eyelashes, the softness of backs of knees and insides of thighs reaching up as far as the dark zone rough to the touch, the wet black thicket between his fingers, the tongue between the teeth and the lips, a body more felt than seen, a body made of pieces of a body, regions of wetness or dryness, open or bosky areas, mounds or clefts, never the body, only its parts, each part a momentary totality in turn immediately split apart, a body segmented, quartered, carved up, chunks of ear ankle groin neck breast fingernail, each piece a sign of the body of bodies, each part whole and entire, each sign an image that appears and burns until it consumes itself, each image a chain of vibrations, each vibration the perception of a sensation that dies away, millions of bodies in each vibration, millions of universes in each body, a rain of universes on the body of Splendor which is not a body but the river of signs of her body, a current of vibrations of sensations of perceptions of images of sensations of vibrations, a fall from whiteness to blackness, blackness to whiteness, whiteness to whiteness, black waves in the pink tunnel, a white fall in the black cleft, never the body but instead bodies that divide, excision and proliferation and dissipation, plethora and abolition, parts that split into parts, signs of the totality that endlessly divides, a chain of perceptions of sensations of the total body that fades away to nothingness.

Almost timidly he caresses the body of Splendor with the palm of his hand, from the hollow of the throat to the feet. Splendor returns the caress with the same sense of astonishment and recognition: her eyes and hands also discover, on contemplating it and touching it, a body that before this moment she had glimpsed and felt only as a disconnected series of momentary visions and sensations, a configuration of perceptions destroyed almost the instant it took shape. A body that had disappeared in her body and that at the very instant of that disappearance had caused her own to disappear: a current of vibrations that are dissipated in the perception of their own dissipation, a perception which is itself a dispersion of all perception but which for that very reason, because it is the perception of disappearance at the very moment it disappears, goes back upstream against the current, and following the path of dissolutions, recreates forms and universes until it again manifests itself in a body: this body of a man that her eyes gaze upon.

On the wall, Splendor is an undulation, the reclining form of sleeping hills and valleys. Activated by the fire whose flames leap up again and agitate the shadows, this mass of repose and sleep begins to stir again. The man speaks, accompanying his words with nods and gestures. On being reflected on the wall, these movements create a pantomime, a feast and a ritual in which a victim is quartered and the parts of the body scattered in a space that continually changes form and direction, like the stanzas of a poem that a voice unfolds on the moving page of the air. The flames leap higher and the wall becomes violently agitated, like a grove of trees lashed by the wind. Splendor’s body is racked, torn apart, divided into one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten parts—until it finally vanishes altogether. The room is inundated with light. The man rises to his feet and paces back and forth, hunching over slightly and seemingly talking to himself. His stooping shadow appears to be searching about on the surface of the wall—smooth, flickering, and completely blank: empty water—for the remains of the woman who has disappeared.

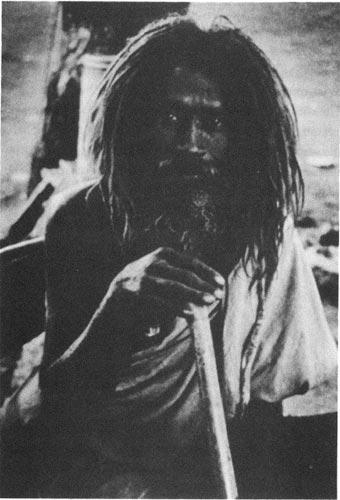

A s dhu of Galta (photograph by Eusebio Rojas).

dhu of Galta (photograph by Eusebio Rojas).

On the wall of the terrace the heroic feats of Hanum

On the wall of the terrace the heroic feats of Hanum n in Lanka are now only a tempest of lines and strokes that intermingle with the purplish damp stains in a confused jumble. A few yards farther on, the stretch of wall ends in a pile of debris. Through the wide breach the surrounding countryside of Galta can be seen: straight ahead, bare forbidding hills that little by little fade away into a parched, yellowish expanse of flat ground, a desolate river valley subjected to the rule of a harsh, slashing light: to the left ravines and rolling hills, and on the slopes or at the tops piles of ruins, some inhabited by monkeys and others by families of pariahs, almost all of them members of the Bal-mik caste (they sweep and wash floors, collect refuse, cart away offal; they are specialists in dust, debris, and excrement, but here, installed amid the ruins and the rubble of the abandoned mansions, they also till the soil on neighboring farms and in the afternoon they gather together in the courtyards and on the terraces to share a hookah, talk together, and tell each other stories); to the right, the twists and turns of the path that leads to the sanctuary at the top of the mountain. A bristling, ocher-colored terrain, sparse thorny vegetation, and scattered here and there, great white boulders polished by the wind. In the bends of the path, standing alone or in groups, powerful trees: pipáis with hanging aerial roots, sinewy, supple arms with which for centuries they have strangled other trees, cracked boulders, and demolished walls and buildings; eucalyptuses with striped trunks and aromatic leaves; neem trees with corrugated, mineral-hard bark—in their fissures and forks, hidden by the acrid green of the leaves, there are colonies of tiny squirrels with huge bushy tails, hermit bats, flocks of crows. Imperturbable skies, indifferent and empty, except for the figures delineated by birds: circles and spirals of eaglets and vultures, ink spots of crows and blackbirds, green zigzag explosions of parakeets.

n in Lanka are now only a tempest of lines and strokes that intermingle with the purplish damp stains in a confused jumble. A few yards farther on, the stretch of wall ends in a pile of debris. Through the wide breach the surrounding countryside of Galta can be seen: straight ahead, bare forbidding hills that little by little fade away into a parched, yellowish expanse of flat ground, a desolate river valley subjected to the rule of a harsh, slashing light: to the left ravines and rolling hills, and on the slopes or at the tops piles of ruins, some inhabited by monkeys and others by families of pariahs, almost all of them members of the Bal-mik caste (they sweep and wash floors, collect refuse, cart away offal; they are specialists in dust, debris, and excrement, but here, installed amid the ruins and the rubble of the abandoned mansions, they also till the soil on neighboring farms and in the afternoon they gather together in the courtyards and on the terraces to share a hookah, talk together, and tell each other stories); to the right, the twists and turns of the path that leads to the sanctuary at the top of the mountain. A bristling, ocher-colored terrain, sparse thorny vegetation, and scattered here and there, great white boulders polished by the wind. In the bends of the path, standing alone or in groups, powerful trees: pipáis with hanging aerial roots, sinewy, supple arms with which for centuries they have strangled other trees, cracked boulders, and demolished walls and buildings; eucalyptuses with striped trunks and aromatic leaves; neem trees with corrugated, mineral-hard bark—in their fissures and forks, hidden by the acrid green of the leaves, there are colonies of tiny squirrels with huge bushy tails, hermit bats, flocks of crows. Imperturbable skies, indifferent and empty, except for the figures delineated by birds: circles and spirals of eaglets and vultures, ink spots of crows and blackbirds, green zigzag explosions of parakeets.

The muffled sound of rocks falling into a torrent: the cloud of dust raised by a flock of little black and tan goats led by two young shepherd boys, one of them playing a tune on a mouth organ and the other humming the words. The cool sound of the footsteps, the voices, and the laughter of a band of women descending from the sanctuary, loaded down with children as though they were fruit-bearing trees, barefoot and perspiring, their arms and ankles decked with many jangling bracelets—the dusty, tumultuous throng of women and the brilliant colors of their garments, violent reds and yellows, their coltlike gait, the tinkle of their laughter, the immensity of their eyes. Farther up, some fifty yards beyond the round fortified tower in ruins that once marked the outer limit of the city, invisible from here (one must branch off to the left and go around a huge rock that stands in the way), the terrain becomes more broken: there is a barrier of boulders and at the foot of them a pool surrounded by heterogeneous buildings. Here the pilgrims rest after performing their ablutions. The spot is also a shelter for wandering ascetics. Among the rocks grow two much-venerated pipal trees. The water of the cascade is green, and the roar it makes as it rushes down makes me think of that of elephants at their bathtime. It is six o’clock; at this hour in the late afternoon the

s dhu

dhu

, the holy man who lives in some nearby ruins, leaves his retreat and, naked from head to foot, heads for the sacred pool. For years, even in the coldest days of December and January, he has performed his ritual ablutions as dawn breaks and as twilight falls. Although he is over sixty years old, he has the body of a young man and his gaze is clear. After his bath in the late afternoon, he recites his prayers, eats the meal that the devout bring to him, drinks a cup of tea and inhales a few puffs of hashish from his pipe or takes a little bhang in a cup of milk—not in order to stimulate his imagination, he says, but in order to calm it. He is searching for equanimity, the point where the opposition between inner and outer vision, between what we see and what we imagine, ceases. I should like to speak with the sadhu, but he does not understand my language and I do not speak his. Hence I limit myself to sharing his tea, his bhang, and his tranquillity from time to time. What does he think of me, I wonder? Perhaps he is now asking himself the same question, if perchance he thinks of me at all.