The Myst Reader (63 page)

Authors: Robyn Miller

“Ah …” But it did not enlighten her.

Duh-nee

. That was what it had sounded like. But where was

Duh-nee?

Deep in the earth? No, that simply wasn’t possible. People didn’t

live

deep in the earth, under the rock. Or did they? Wasn’t that, after all, what she had been staring at every day for these past six months? Rock, and yet more rock.

The securing rope was cast off, the oarsmen to her left pushed away from the side. Suddenly they were gliding down the channel, the huge walls slipping past her as the oars dug deep in unison.

Anna turned, looking back, her eyes going up to the great carved circle of the arch that had been cut into the massive stone wall of the cave; a counterpart, no doubt, to the arch on the far side. The wall itself went up and up and up. She craned her neck, trying to see where it ended, but the top of it was in shadow.

She sniffed the air. Cool, clean air, like the air of the northern mountains of her home.

Outside. They

had

to be outside. Yet the captain had said quite clearly that this was a cavern.

She shook her head in disbelief. No cavern she had ever heard of was this big. It had to be …

miles

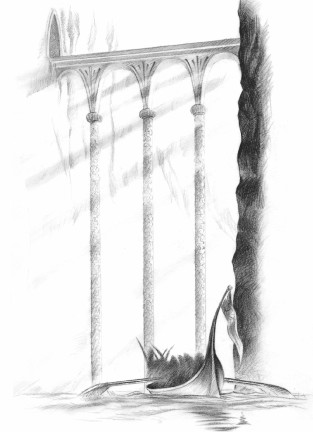

across. Turning, she looked to the captain. He was standing at the prow, staring directly ahead. Beyond him, where the channel turned to the right, a bridge had come into view—a pale, lacelike thing of stone, spanning the chasm, the carving on its three, high-arched spans as delicate as that on a lady’s ivory fan.

Passing under the bridge the channel broadened, the steep sides of the chasm giving way to the gentler, more rounded slope of hills, the gray and black of rock giving way to a mosslike green. Ahead of them lay a lake of some kind, the jagged shapes of islands visible in the distance, strangely dark amid that huge expanse of glowing water.

At first Anna did not realize what she was looking at; then, with a start, she saw that what she had thought were strange outcrops of rock were, in fact, buildings; strangely shaped buildings that mimicked the flowing forms of molten rock. Buildings that had no roofs.

That last made a strange and sudden sense to her. So they

were

inside. And the water. Of course … Something must be in the water to make it glow like that.

As the boat glided out onto the lake itself, Anna took in for the first time the sheer scale of the cavern.

“It’s magnificent,” she said quietly, awed by it.

The captain turned, glancing at her, surprised by her words. Then, as if conceding something to her, he pointed to his right.

“There. That is where we are headed. See? Just beyond the bluff. It will come into sight in a moment.”

There was a pillar of some kind—a lighthouse maybe, or a monument—just beyond the great heap of rock that lay directly to their right, the top of it jutting up above the bluff. Yet as they rounded the headland, she saw, with astonishment, that the pillar was not as close as she had presumed. Indeed, it lay a good two or three miles distant.

“But it’s …”

“Over three hundred and fifty spans high.”

Anna stared at the great column of twisted rock that lay at the center of the glowing lake. Three hundred and fifty spans! That was over a mile by her own measure! Somehow it didn’t seem natural. The rock looked as if it had been shaped by some giant hand. Looking at it, she wasn’t sure whether it was hideous or beautiful; her eyes were not trained to appreciate so alien an aesthetic.

“What is it called?”

“The ancients called it Ae’Gura,” he answered, “but we simply call it The Island. The city is beyond it, to its right.”

“The city?”

But it was clear that he felt he had said too much already. He looked away, falling silent once again, only the swish of the oars in the water and the creak of the boat as it moved across the lake breaking the eerie silence.

VEOVIS SAT IN THE CORRIDOR OUTSIDE LORD

Eneah’s study, waiting, while, beyond the door, the elders finished their discussion.

He had been summoned at a moment’s notice, brought here in the Great Lord’s own sedan. That alone said much. Something must have happened—something that the elders wished urgently to consult him about.

Veovis smiled. He had known these men since childhood. He had seen them often with his father, in both formal and informal settings. They ate little and spoke only when a matter of some importance needed uttering. Most of what was “said” between them was a matter of eye contact and bodily gesture, for they had known each other now two centuries and more, and there was little they did not know of each other. He, on the other hand, represented a more youthful, vigorous strain of D’ni thinking. He was, as they put it, “in touch” with the living pulse of D’ni culture.

Veovis knew that and accepted it. Indeed, he saw it as his role to act as a bridge between the Five and the younger members of the Council, to reconcile their oft-differing opinions and come up with solutions that were satisfactory to all. Like many of his class, Veovis did not like, nor welcome, conflict, for conflict meant change and change was anathema to him. The Five had long recognized that and had often called on him to help defuse potentially difficult situations before push came to shove.

And so now, unless he was mistaken.

As the door eased open, Veovis got to his feet. Lord Eneah himself stood there, framed in the brightly lit doorway, looking out at him.

“Veovis. Come.”

He bowed, his respect genuine. “Lord Eneah.”

Stepping into the room, he looked about him, bowing to each of the Great Lords in turn, his own father last of all. It was exactly as he had expected; only the Five were here. All others were excluded from this conversation.

As Eneah sat again, in the big chair behind his desk, Veovis stood, feet slightly apart, waiting.

“It is about the intruder,” Eneah said without preamble.

“It seems she is ready,” Lord Nehir of the Stone-Masons, seated to Veovis’s right, added.

“Ready, my Lords?”

“Yes, Veovis,” Eneah said, his eyes glancing from one to another of his fellows, as if checking that what he was about to say had their full approval. “Far more ready, in fact, than we had anticipated.”

“How so, my Lord?”

“She speaks D’ni,” Lord R’hira of the Maintainers answered.

Veovis felt a shock wave pass through him. “I beg your pardon, Lord R’hira?”

But R’hira merely stared at him. “Think of it, Veovis. Think what that means.”

But Veovis could not think. The very idea was impossible. It had to be some kind of joke. A test of him, perhaps. Why, his father had said nothing to him of this!

“I …”

“Grand Master Gihran of the Guild of Linguists visited us earlier today,” Lord Eneah said, leaning forward slightly. “His report makes quite remarkable reading. We were aware, of course, that some progress was being made, but just how much took us all by surprise. It would appear that our guest is ready to face a Hearing.”

Veovis frowned. “I do not understand …”

“It is very simple,” Lord Nehir said, his soft voice breaking in. “We must decide what is to be done. Whether we should allow the young woman to speak openly before the whole Council, or whether she should be heard behind closed doors, by those who might be trusted to keep what is heard to themselves.”

“The High Council?”

His father, Lord Rakeri, laughed gruffly. “No, Veovis. We mean the Five.”

Veovis went to speak then stopped, understanding suddenly what they wanted of him.

Lord Eneah, watching his face closely, nodded. “That is right, Veovis. We want you to make soundings for us. This is a delicate matter, after all. It might, of course, be safe to let the girl speak openly. On the other hand, who knows what she might say? As the custodians of D’ni, it is our duty to assess the risk.”

Veovis nodded, then, “Might I suggest something, my Lords?”

Eneah looked about him. “Go on.”

“Might we not float the idea of

two

separate Hearings? The first before the Five, and then a second—possibly—once you have had the opportunity to judge things for yourselves?”

“You mean, promise something that we might not ultimately grant?”

“The second Hearing would be dependent on the success of the first. That way you have safeguards. And if things go wrong …”

Eneah was smiling now, a wintry smile. “Excellent,” he said. “Then we shall leave it to you, Veovis. Report back to us within three days. If all is well, we shall see the girl a week from now.”

Veovis bowed low. “As you wish, my Lords.”

He was about to turn and leave, when his father, Rakeri, called him back. “Veovis?”

“Yes, father?”

“Your friend, Aitrus.”

“What of him, father?”

“Recruit him if you can. He’s a useful fellow, and well liked among the new members. With him on your side things should prove much easier.”

Veovis smiled, then bowed again. “As you wish, father.” Then, with a final nod to each of them in turn, he left.

ENEAH SAT AT HIS DESK LONG AFTER THEY HAD

gone, staring at the open sketch pad and the charcoal image of his face. It was some time since he had stared at himself so long or seen himself so clearly, and the thought of what he had become, of the way that time and event had carved his once familiar features, troubled him.

He was, by nature, a thoughtful man; even so, his thoughts were normally directed outward, at that tiny, social world embedded in the rock about him. Seldom did he stop to consider the greater world within himself. But the girl’s drawing had reminded him. He could see now how hope and loss, ambition and disappointment, idealism and the longer, more abiding pressures of responsibility, had marked his flesh. He had thought his face a kind of mask, a stone lid upon the years, but he had been wrong: It was all there, engraved in the pale stone of his skin, as on a tablet, for all who wished to read.

If she is typical …

The uncompleted thought, like the drawing, disturbed him deeply. When he had agreed to the Hearings, he had thought, as they had all thought, that the matter was a straightforward one. The savage would be brought before them, and questioned, and afterward disposed of—humanely, to a Prison Age—and then, in time, forgotten. But the girl was not a simple savage.

Eneah closed the sketch pad, then sighed wearily.

“If she is typical …”