The New Penguin History of the World (94 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Investiture ran on as an issue for the next fifty years. Gregory lost the sympathy he had won through Henry’s bullying and it was not until 1122 that another emperor agreed to a concordat which was seen as a papal victory, though one diplomatically disguised. Yet Gregory had been a true pioneer; he had differentiated clerics and laymen as never before and had made unprecedented claims for the distinction and superiority of papal power. More would be heard of them in the next two centuries. Though his immediate successors acted less dramatically than he, they steadily pressed papal claims to papal advantage. Urban II used the first crusade to become the diplomatic leader of Europe’s lay monarchs; they looked to Rome, not the empire. Urban also built up the Church’s administrative machine; under him emerged the

curia

, a Roman bureaucracy which corresponded to the household administrations of the English and French kings. Through it the papal grip on the Church itself was strengthened. In 1123, a historic date, the first ecumenical council was held in the West and its decrees were promulgated in the pope’s own name. And all the time, papal jurisprudence and jurisdiction ground away; more and more legal disputes found their way from the local church courts to papal judges, whether resident at Rome, or sitting locally.

Prestige, dogma, political skill, administrative pressure, judicial practice and the control of more and more benefices all buttressed the new ascendancy of the papacy within the Church. By 1100 the groundwork was done for the emergence of a true papal monarchy. As the investiture contest receded, secular princes were on the whole well disposed to Rome and it appeared that no essential ground had been lost by the papacy. There was indeed a spectacular quarrel in England over the question of clerical privilege and immunity from the law of the land which would be an issue of the future; immediately, it provoked the murder (and then the canonization) of Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury. But on the whole, the large legal immunities of clergy were not much challenged.

Under Innocent III papal pretensions to monarchical authority reached a new theoretical height. True, Innocent did not go quite so far as Gregory.

He did not claim an absolute plenitude of temporal power everywhere in western Christendom, but he said that the papacy had by its authority transferred the empire from the Greeks to the Franks. Within the Church his power was limited by little but the inadequacies of the bureaucratic machine through which he had to operate. Yet papal power was still often deployed in support of the reforming ideas – which shows that much remained to be done. Clerical celibacy became more common and more widespread. Among new practices which were pressed on the Church in the thirteenth century was that of frequent individual confession, a powerful instrument of control in a religiously minded and anxiety-ridden society. Among doctrinal innovations, the theory of transubstantiation, that by a mystical process the body and blood of Christ were actually present in the bread and wine used in the communion service, was imposed from the thirteenth century onwards.

The final christening of Europe in the central Middle Ages was a great spectacle. Monastic reform and papal autocracy were wedded to intellectual effort and the deployment of new wealth in architecture to make this the next peak of Christian history after the age of the Fathers. It was an achievement whose most fundamental work lay, perhaps, in intellectual and spiritual developments, but it became most visible in stone. What we think of as ‘Gothic’ architecture was the creation of this period. It produced the European landscape which, until the coming of the railway, was dominated or punctuated by a church tower or spire rising above a little town. Until the twelfth century the major buildings of the Church were usually monastic; then began the building of the astonishing series of cathedrals, especially in northern France and England, which remains one of the great glories of European art and, together with castles, constitutes the major architecture of the Middle Ages. There was great popular enthusiasm, it seems, for these huge investments, though it is difficult to penetrate to the mental attitudes behind them. Analogies might be sought in the feeling of twentieth-century enthusiasts for space exploration, but this omits the supernatural dimension of these great buildings. They were both offerings to God and an essential part of the instrumentation of evangelism and education on earth. About their huge naves and aisles moved the processions of relics and the crowds of pilgrims who had come to see them. Their windows were filled with the images of the biblical story which was the core of European culture; their façades were covered with the didactic representations of the fate awaiting just and unjust. Christianity achieved in them a new publicity and collectiveness. Nor is it possible to assess the full impact of these great churches on the imagination of medieval Europeans without reminding ourselves how much greater was the contrast

their splendour presented to the reality of everyday life than any imaginable today.

The power and penetration of organized Christianity were further reinforced by the appearance of new religious orders. Two were outstanding, the mendicant Franciscans and Dominicans, who in England came to be called respectively the Grey and Black Friars, from the colours of their habits. The Franciscans were true revolutionaries: their founder, St Francis of Assisi, left his family to lead a life of poverty among the sick, the needy and the leprous. The followers who soon gathered about him eagerly took up a life directed towards the imitation of Christ’s poverty and humility. There was at first no formal organization and Francis was never a priest, but Innocent III, shrewdly seizing the opportunity of patronizing this potentially divisive movement instead of letting it escape from control, bade them elect a Superior. Through him the new fraternity owed and maintained rigorous obedience to the Holy See. They could provide a counterweight to local episcopal authority because they could preach without the licence of the bishop of the diocese. The older monastic orders recognized a danger and opposed the Franciscans, but the friars prospered, despite internal quarrels about their organization. In the end they acquired a substantial administrative structure of their own, but they always remained peculiarly the evangelists of the poor and the mission field.

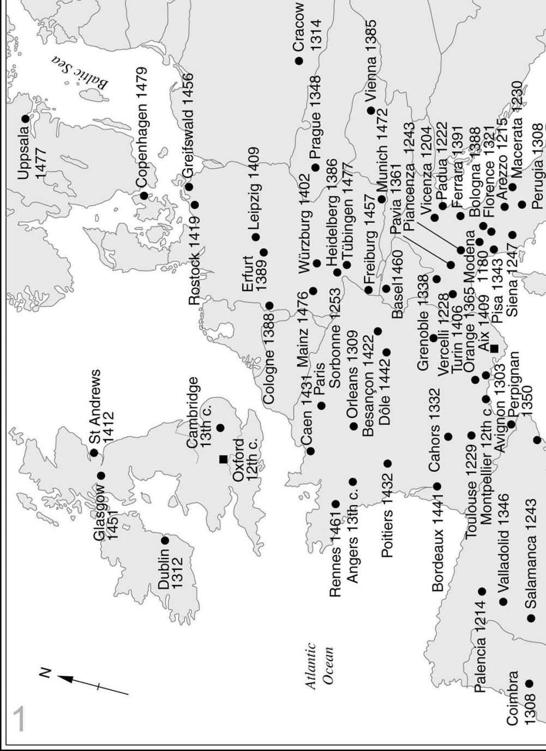

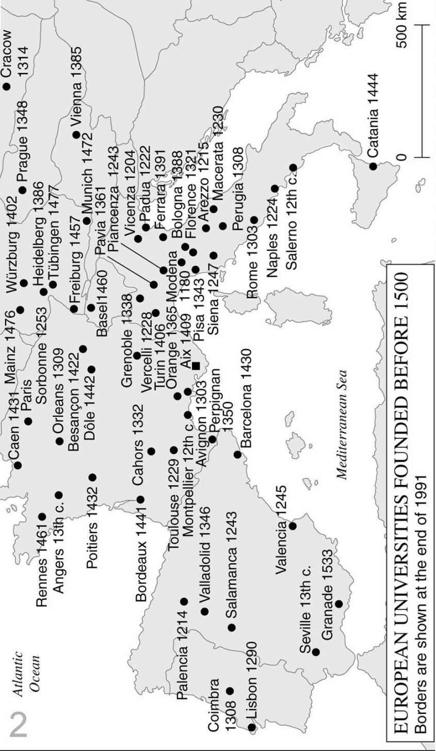

The Dominicans sought to further a narrower end. Their founder was a Castilian priest who went to preach in the Languedoc to heretics, the Albigensians. From his companions grew a new preaching order; when Dominic died in 1221 his seventeen followers had become over five hundred friars. Like the Franciscans, they were mendicants vowed to poverty, and like them, too, they threw themselves into missionary work. But their impact was primarily intellectual and they became a great force in a new institution of great importance, just taking shape, the first universities. Dominicans came also to provide many of the personnel of the Inquisition, an organization to combat heresy, which appeared in the early thirteenth century. From the fourth century onwards, churchmen had urged the persecution of heretics. Yet the first papal condemnation of them did not come until 1184. Only under Innocent III did persecution come to be the duty of Catholic kings. The Albigensians were certainly not Catholic, but there is some doubt whether they should really be regarded even as Christian heretics. Their beliefs reflect Manichaean doctrines. They were dualists, some of whom rejected all material creation as evil. Like those of many later heretics, heterodox religious views were taken to imply aberration or at least nonconformity in social and moral practices. Innocent III seems to have decided to persecute the Albigensians after the murder of a papal

legate in the Languedoc and in 1209 a crusade was launched against them. It attracted many laymen (especially from northern France) because of the chance it offered for a quick grab at the lands and homes of the Albigensians, but it also marked a great innovation: the joining of State and Church in western Christendom to crush by force dissent which might place either in danger. It was for a long time an effective device, though never completely so.

In judging the theory and practice of medieval intolerance it must be remembered that the danger in which society was felt to stand from heresy was appalling: its members might face everlasting torment. Yet persecution did not prevent the appearance of new heresies again and again in the next three centuries, because they expressed real needs. Heresy was, in one sense, an exposure of a hollow core in the success which the Church had so spectacularly achieved. Heretics were living evidence of dissatisfaction with the outcome of a long and often heroic battle. Other critics would also make themselves heard in due course and different ways. Papal monarchical theory provoked counter-doctrine; thinkers would argue that the Church had a defined sphere of activity which did not extend to meddling in secular affairs. As men became more conscious of national communities and respectful of their claims, this would seem more and more appealing. The rise of mystical religion was yet another phenomenon always tending to slip outside the ecclesiastical structure. In movements like the Brethren of the Common Life, following the teachings of the mystic Thomas à Kempis, laymen created religious practices and devotional forms which sometimes escaped from clerical control.

Such movements expressed the great paradox of the medieval Church. It had risen to a pinnacle of power and wealth. It deployed vast estates, tithes and papal taxation in the service of a magnificent hierarchy, whose worldly greatness reflected the glory of God and whose lavish cathedrals, great monastic churches, splendid liturgies, learned foundations and libraries embodied the devotion and sacrifices of the faithful. Yet the point of this huge concentration of power and grandeur was to preach a faith at whose heart lay the glorification of poverty and humility and the superiority of things not of this world.

The worldliness of the Church drew increasing criticism. It was not just that a few ecclesiastical magnates lolled back upon the cushion of privilege and endowment to gratify their appetites and neglect their flocks. There was also a more subtle corruption inherent in power. The identification of the defence of the faith with the triumph of an institution had given the Church an increasingly bureaucratic and legalistic face. The point had arisen as early as the days of St Bernard; even then, there were too many ecclesiastical lawyers, it was said. By the mid-thirteenth century legalism was blatant. The papacy itself was soon criticized. At the death of Innocent III the Church of comfort and of the sacraments was already obscured behind the granite face of centralization. The claims of religion were confused with the assertiveness of an ecclesiastical monarchy demanding freedom from constraint of any sort. It was already difficult to keep the government of the Church in the hands of men of spiritual stature; Martha was pushing Mary aside, because administrative and legal gifts were needed to run a machine which more and more generated its own purposes.

In 1294 a hermit of renowned piety was elected pope. The hopes this roused were quickly dashed. Celestine V was forced to resign within a few weeks, seemingly unable to impose his reforming wishes on the

curia

. His successor was Boniface VIII. He has been called the last medieval pope because he embodied all the pretensions of the papacy at its most political and its most arrogant. He was by training a lawyer and by temperament far from a man of spirituality. He quarrelled violently with the kings of England and France and in the Jubilee of 1300 had two swords carried before him to symbolize his possession of temporal as well as spiritual power. Two years later he asserted that a belief in the sovereignty of the pope over every human being was necessary to salvation.