The New Penguin History of the World (97 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

By that time the empire had virtually ceased to matter south of the Alps. The struggle to preserve it there had long been tangled with Italian politics: the contestants in feuds which tormented Italian cities called themselves Guelph and Ghibelline long after those names ceased to mean, as they formerly did, allegiance respectively to pope or emperor. After the fourteenth century there was no imperial domain in Italy and emperors hardly went there except to be crowned with the Lombard crown. Imperial authority was delegated to ‘vicars’ who made of their vicariates units almost as independent as the electorates of Germany. Titles were given to these rulers and their vicariates, some of which lasted until the nineteenth century; the duchy of Milan was one of the first. But other Italian states had different origins. Besides the Norman south, the ‘kingdom of the Two Sicilies’, there were the republics, of which Venice, Genoa and Florence were the greatest.

The city republics represented the outcome of two great trends sometimes interwoven in early Italian history, the ‘communal’ movement and the rise of commercial wealth. In the tenth and eleventh centuries, in much of north Italy, general assemblies of the citizens had emerged as effective governments in many towns. They described themselves sometimes as

parliamenta

or, as we might say, town meetings, and represented municipal oligarchies who profited from a revival of trade beginning to be felt from 1100 onwards. In the twelfth century the Lombard cities took the field against the emperor and beat him. Thereafter they ran their own internal affairs.

A golden age for Italy was just beginning which was to last well into

the fourteenth century. It was marked by a striking increase of wealth, based on both manufacturing (mainly of textiles) and commerce. But its glory was a cultural efflorescence, which was expressed not only in what contemporaries saw as a rebirth of classical learning, but also in the creation of a vernacular literature, in music, and in all the visual and plastic arts. Its triumphs were widely diffused throughout the peninsula, but above all were visible in Florence, under the nominally republican but actually monarchical government of the Medici, a family whose fortune was rooted in banking. The greatest beneficiary of the revival of trade, though, was Venice. Formally a Byzantine dependency, it was long favoured by the detachment from the troubles of the European mainland accorded by its position on a handful of islands in a shallow lagoon. Men had already fled there from the Lombards. Besides offering security, geography also imposed a destiny; Venice, as its citizens loved later to remember, was wedded to the sea, and a great festival of the Republic commemorated it by the symbolic act of throwing a ring into the waters of the Adriatic. Venetian citizens were forbidden to acquire estates on the mainland and instead turned their energies to commercial empire overseas. Venice became the first west European city to live by trade. It was also the most successful of those who pillaged and battered on the eastern empire after winning a long struggle with Genoa for commercial supremacy in the East. There was plenty to go around: Genoa, Pisa and the Catalan ports all prospered with the revival of Mediterranean trade with the East.

Much of the political ground-plan of modern Europe was, therefore, in being by 1500. Portugal, Spain, France and England were recognizable in their modern form, but although in Italy and Germany the vernacular had begun to define nationhood, there was no correspondence in them between nation and state. State structures, too, were still far from enjoying the firmness and coherence they later acquired. The kings of France were not kings of Normandy but dukes. Different titles symbolized different legal and practical powers in different provinces. There were many such complicated survivals; constitutional relics everywhere cluttered up the idea of monarchical sovereignty, and they could provide excuses for rebellion. One explanation of the success of Henry VII, the first of the Tudors, was that by judicious marriages he drew much of the remaining poison from the bitter struggle of great families which had bedevilled the English Crown in the fifteenth-century Wars of the Roses. Yet there were still to be feudal rebellions to come.

One limitation on monarchical power had appeared which has a distinctly modern look. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries can be found the first examples of the representative, parliamentary bodies which are so

characteristic of the modern state. The most famous of them all, the English parliament, was the most mature by 1500. Their origins are complex and have been much debated. One root is Germanic tradition, which imposed on a ruler the obligation of taking counsel from his great men and acting on it. The Church, too, was an early exponent of the representative idea, using it, among other things, to obtain taxation for the papacy. It was a device which united towns with monarchs, too: in the twelfth century representatives from Italian cities were summoned to the diet of the empire. By the end of the thirteenth century most countries had seen examples of representatives with full powers being summoned to attend assemblies which princes had called to find new ways of raising taxation.

This was the nub of the matter. New resources had to be tapped by the new (and more expensive) state. Once summoned, princes found representative bodies had other advantages. They enabled voices other than those of the magnates to be heard. They provided local information. They had a propaganda value. On their side, the early parliaments (as we may loosely call them) of Europe were discovering that the device had advantages for them, too. In some of them the thought arose that taxation needed consent and that someone other than the nobility had an interest and therefore ought to have a voice in the running of the realm.

WORKING AND LIVING

From about the year 1000 another fundamental change was under way in Europe: it began to get richer. As a result, more men slowly acquired a freedom of choice almost unknown in earlier times; society became more varied and complicated. Slow though it was, this was a revolution; society’s wealth at last began to grow a little faster than population. This was by no means obvious everywhere to the same degree and was punctuated by a bad setback in the fourteenth century. Yet the change was decisive and launched Europe on a trajectory of economic growth lasting to our own day.

One crude but by no means misleading index is the growth of population. Only approximate estimates can be made but they are based on better evidence than is available for any earlier period. The errors they contain are unlikely much to distort the overall trend. They suggest that a Europe of about forty million people in 1000 rose to sixty million or so in the next two centuries. Growth then seems to have further accelerated to reach a peak of about seventy-three million around 1300, after which there is indisputable evidence of decline. The total population is said to have gone

down to about fifty million by 1360 and only to have begun to rise in the fifteenth century. Then it began to go up again, and overall growth has been uninterrupted ever since.

Of course, the rate of increase varied even from village to village. The Mediterranean and Balkan lands did not succeed in doubling their population in five centuries and by 1450 had relapsed to levels only a little above those of 1000. The same appears to be true of Russia, Poland and Hungary. Yet France, England, Germany and Scandinavia probably trebled their populations before 1300 and after bad setbacks in the next hundred years still had twice the population of the year 1000. Contrasts within countries could be made, too, sometimes between areas very close to one another, but the general effect is indisputable: population grew overall as never before, but unevenly, the north and west gaining more than the Mediterranean, Balkan and eastern Europe.

The explanation lies in food supply, and therefore in agriculture. It was for a long time the only possible major source of new wealth. More food was obtained by bringing more land under cultivation and by increasing its productivity. Thus began the rise in food production which has gone on ever since. Europe had great natural advantages (which she has retained) in her moderate temperatures and good rainfall and these, combined with a physical relief whose predominant characteristic is a broad northern plain, have always given her a large area of potentially productive agricultural land. Huge areas of it still wild and forested in 1000 were brought into cultivation in the next few centuries.

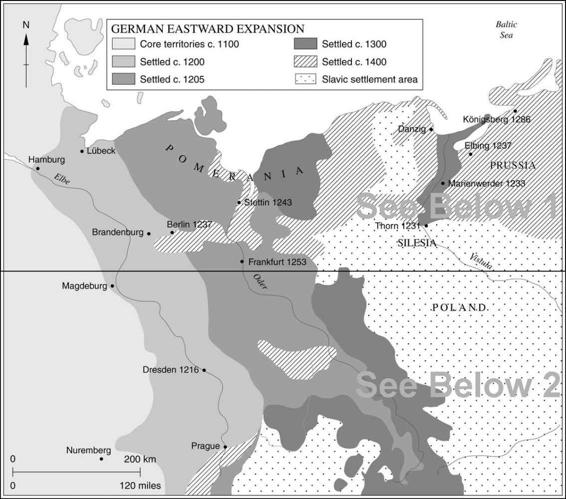

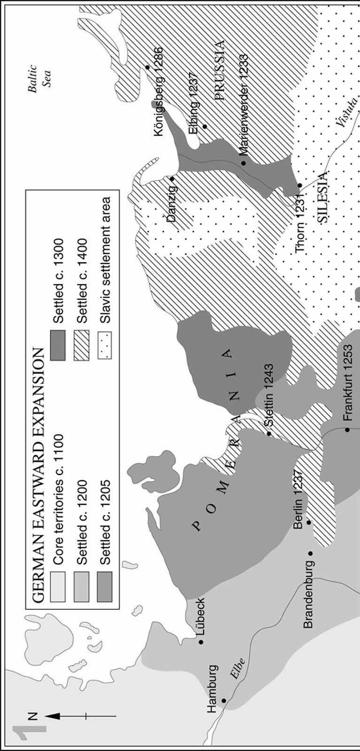

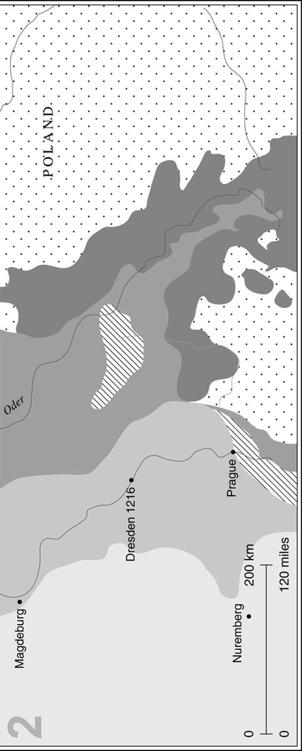

Land was not short in medieval Europe and a growing population provided the labour to clear and till it. Though slowly, the landscape changed. The huge forests were gradually cut into as villages pushed out their fields. In some places, new colonies were deliberately established by landlords and rulers. The building of a monastery in a remote spot – as many were built – was often the beginning of a new nucleus of cultivation or stock-raising in an almost empty desert of scrub and trees. Some new land was reclaimed from sea or marsh. In the east, much was won in the colonization of the first German

Drang nach Osten

. Settlement there was promoted as consciously as it was later to be promoted in Elizabethan England in the first age of North American colonization.

By about 1300, the breaking-in of new land slowed down. There were even signs of over-population. Smaller holdings, shortage of livestock and manure, pressure on pasture – symptoms of rural dislocation such as are now associated with Third World countries – became more obvious. The first big increase in Europe’s cultivated and grazed areas was over after underpinning an indispensable increase in production. Some have argued

that in some parts of western Europe output had doubled. Besides having more land brought under cultivation, this also owed something to better husbandry; it showed the effect of increased use of regular fallows and cropping, the gradual enrichment of the soil, and even the introduction of some new crops. Although grain-growing was still the main business of the cultivator in northern Europe, the appearance of beans and peas of various sorts in larger quantities from the tenth century onwards meant that more nitrogen was being returned to the soil. Cause and effect are difficult to disentangle in economic history; other suggestive signs of change go along with these. In the thirteenth century the first manuals of agricultural practice appear and the first agricultural bookkeeping, a monastic innovation. More specialized cultivation brought a tendency to employ wage labourers instead of serfs carrying out obligatory work. By 1300 it is likely that most household servants in England were recruited and paid as free labour and probably a third or so of the peasants as well. The bonds of servitude were relaxing and a money economy was spreading slowly into the countryside.

For all that, most people remained miserably poor. Some peasants benefited, but increased wealth usually went to the landlord who took most of the profits. Most still lived poor and cramped lives, eating coarse bread and various grain-based porridges, seasoned with vegetables and only occasionally fish or meat. Calculations suggest the peasant consumed about two thousand calories daily (very much what was the average daily intake of a Sudanese in the late twentieth century), and this had to sustain him for very laborious work. If he grew wheat he did not eat its flour, but sold it to the better-off, keeping barley or rye for his own food. He had little elbow-room to better himself. Even when his lord’s legal grip through bond labour became less firm, the lord still had practical monopolies of mills and carts, which the peasants needed to work the land. ‘Customs’, or taxes for protection, were levied without regard to distinctions between freeholders and tenants and could hardly be resisted.