The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (15 page)

A dove house filled with doves and Pigeons

Shudders Hell thro’ all its regions.

That couplet does conform with the plan, the second line is completely trochaic, with weak ending and all, but now Blake continues with:

A dog starv’d at his Master’s Gate

Predicts the ruin of the State.

Those are both iambic lines. And the next couplet?

A Horse misus’d upon the Road

Calls to Heaven for Human blood

Well, I mean I’m sorry, but that’s just plain bad. Isn’t it? The

syntax

(grammatical construction) for a start: bit wobbly isn’t it? Does he really mean that the

horse

is calling to heaven: the other animals don’t, surely he means the misuse of horses calls to heaven? But Blake’s sentence structure invites us to picture a calling horse. And, my dear, the

scansion

! Presumably Blake means to elide Heaven into the monosyllable Heav’n (a perfectly common elision and one we might remember having to sing in school hymns), but it is odd that he bothers in earlier lines to put apostrophes in ‘starv’d’ and ‘misus’d’ and even shortens

through

to

thro’

24

yet fails to give us an apostrophe here where it really would count: he has already used the word Heaven once

without

elision, as a disyllabic word, six lines earlier: perhaps, one might argue, he felt that as a holy word it shouldn’t be altered in any way. I think this unlikely, he tends not to use capitals for God, although he uses them for ‘Me’ and ‘My’ and just about every word he can (incidentally, why does Horse deserve majuscules here, but not dog, I wonder? Why Pigeon and not dove?). Well, perhaps the unelided ‘Heaven’ is a misprint: if so, it is one that all the copies

25

of Blake I have seen repeat. It is fairly obvious that this is how he wrote it in his manuscript.

No, I think we can confidently state that there is no metrical

scheme

in place here: Blake seems to be in such a hurry to list the abominable treatment that animals suffer and the dire consequences attendant upon mankind if this cruelty continues that measured prosody has taken a back seat. Well, may be that’s the point. Any kind of control or cunning in versification would mediate between Blake’s righteous indignation and the conscience and compassion of the reader, resulting in ‘better’ metre perhaps, but less direct and emotionally involving poetry. A more conventional poet might have written something like this:

Robin redbreasts in a cage

Put all heaven in a rage

Dovecotes filled with doves and pigeons

Shudder hell through all its regions

Dogs starved at their masters’ gate

Augur ruin for the state.

Horses beaten on the road

Call to Heav’n for human blood.

There

is

a loss there: Blake’s point is that

a

robin, one single caged bird, is enough to put heaven in a rage (admittedly that isn’t true of the dove house, which has to be filled to cause hell to shudder, but no matter). Pluralising the animals for the sake of trochees does alter the sense, so let us try pure iambs:

A robin redbreast in a cage

Doth put all heaven in a rage.

A dove house filled with doves and pigeons

Will shudder hell through all its regions.

A dog starved at his master’s gate

Predicts the ruin of the state.

A horse misused upon the road

Doth call to heav’n for human blood.

Neither, incidentally, solves the curious incident of the dog starved

at

his master’s gate: trochaic or iambic, the line’s a bitch. Surely it is the

starving

that needs the emphasis? ‘A dog that starves at’s master’s gate’ would do it, but it isn’t nice.

We have seen two non-hybrid versions of the verse. Let us now remind ourselves of what Blake actually gave us:

A Robin Red breast in a Cage

Puts all Heaven in a Rage.

A dove house filled with doves and Pigeons

Shudders Hell thro’ all its regions.

A dog starv’d at his Master’s Gate

Predicts the ruin of the State.

A Horse misus’d upon the Road

Calls to Heaven for Human blood.

I have mocked the scansion, syntax and manifold inconsistencies; I have had sport with these lines, but the fact is I love them. They’re messy, mongrel and mawkish but such is the spirit of Blake that somehow these things don’t matter at all–they only go to convince us of the work’s fundamental honesty and authenticity. Am I saying this because Blake is Blake and we all know that he was a Seer, a Visionary and an unique Genius? If I had never seen the lines before and didn’t know their author would I forgive them their clumsiness and ill-made infelicities? I don’t know and I don’t really care. It is a work concerned with innocence after all. And, lest we forget, this is the poem that begins with the

quatrain

(a quatrain is a stanza of four lines) that might usefully be considered the Poet’s Credo or Mission Statement.

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

The metre is shot to hell in every line, but who cares. It is the real thing. I think it was worth spending this much time on those lines because this is what you will do when you write your own verse–constantly make series of judgements about your metre and what ‘rules’ you can break and with what effect.

Poetry Exercise 5

It is now time, of course, to try writing your own verse of shorter measure. Here is what I want you to do: give yourself forty-five minutes; if you haven’t got the time now, come back to the exercise later. I believe it is much simpler if you have a subject, so I have selected

Television

. As usual I have had a go myself. Rhyming seems natural with lines of this length, but if you’d rather not, then don’t. I remind you once again that it is the versification that matters here, not any verbal or metaphysical brilliance. This is what I would like, with my attempts included.

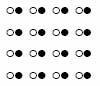

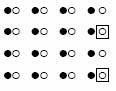

- Two quatrains of standard, eight-syllable iambic tetrameter:

They’re always chopping bits of meat–

Forensic surgeons, daytime cooks.

Extracting bullets, slicing ham

Detecting flavours, grilling crooks.

My new TV has got no knobs

It’s sleeker than a marble bowl.

I’m sure this suits designer snobs,

But where’s the damned remote control?

- Two quatrains of alternating iambic tetrameter and trimeter:

Big Brother’s on the air again,

Polluting my TV.

Who was it said, ‘Mankind can’t bear

Too much reality?

26

Sir Noël Coward drawled, when asked

Which programmes he thought shone:

‘TV is not for watching, dear–

It’s just for being on.’

- Two quatrains of

trochaic

tetrameter: one in ‘pure trochee’ à la

Hiawatha

, and one with docked weak endings in the second and fourth lines, à la ‘Tyger’.

Soap stars seem to do it nightly–

Slap and shag and rape each other.

If I heard the plot-line rightly

Darren’s pregnant by his brother.

News of bombs in Central London,

Flesh and blood disintegrate.

Teenage voices screaming proudly,

‘Allah akbar! God is great!’

So, your turn. Relax and feel the force.

IV

Ternary Feet: we meet the anapaest and the dactyl, the molossus, the tribrach, the amphibrach and the amphimacer

Ternary Feet

Now that you are familiar with four types of two-syllable, binary (or

duple

as a musician might say) foot–the

iamb

, the

trochee

, the

pyrrhic

and the

spondee

–try to work out what is going on metrically in the next line.

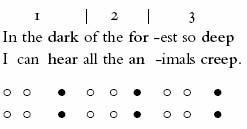

In the dark of the forest so deep

I can hear all the animals creep.

Did you get the feeling that the only way to make sense of this metre is to think of the line as having feet with

three

elements to them, the third one bearing the beat? A kind of Titty-

tum

, titty-

tum

, titty-

tum

triple rhythm? A

ternary foot

in metric jargon, a

triple measure

in music-speak.

Such a titty-

titty-

tum

foot is called an

anapaest

, to rhyme with ‘am a beast’, as if the foot is a skiing champion, Anna Piste. It is a ternary version of the iamb, in that it is a

rising

foot, going from weak to strong, but by way of

two

unstressed syllables instead of the iamb’s one.