The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs (2 page)

Read The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs Online

Authors: Elaine Sciolino

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #History, #Biography, #Adventure

. . .

The rue des Martyrs is the center of France.

— S

IOBHAN

M

LACAK

,

NEIGHBORHOOD PHOTOGRAPHER

The rue des Martyrs is the center of the world.

—L

ILIANE

K

EMPF, RESIDENT OF

THE RUE DES MARTYRS FOR FIFTY YEARS

S

OME PEOPLE LOOK AT THE RUE DES MARTYRS AND

see a street. I see stories.

For me, it is the last real street in Paris, a half-mile celebration of the city in all its diversity—its rituals and routines, its permanence and transience, its quirky old family-owned shops and pretty young boutiques. This street represents what is left of the intimate, human side of Paris.

I can never be sad on the rue des Martyrs. There are espressos to drink, baguettes to sniff, corners to discover, people to meet. There’s a showman who’s been running a transvestite cabaret for

more than half a century, a woman who repairs eighteenth-century mercury barometers, and an owner of a century-old bookstore with a passion for left-wing philosophers. There are merchants who seduce me with their gastronomic passions: artichokes so young they can be served raw, a Côtes du Rhône so smooth it could be a fine Burgundy, a Mont d’Or cheese so creamy it is best eaten with a spoon. The small food shops on the lower end have no doors. That makes them cold in winter, hot in summer, damp when it rains, and inviting no matter what the weather.

The shopkeepers enforce a culinary camaraderie that has helped me discover my inner Julia Child. What Child wrote in

My Life in France

resonates here as in no other place: “The Parisian grocers insisted that I interact with them personally. If I wasn’t willing to take the time to get to know them and their wares, then I would not go home with the freshest legumes or cuts of meat in my basket. They certainly made me work for my supper—but, oh, what suppers!”

Like Julia, I interact personally. I work for my supper. I caress tomatoes, inspect veal chops, sniff ripe Camembert, sample wild boar charcuterie, and go wobbly over buttery brioche. The foodsellers watch, bemused. I have been introduced to a sweet turnip with yellow stripes named “Ball of Gold”; I have been taught to liberate a raw almond from its skin by slamming it into a wall. Sometimes I even pretend to be Julia, who, like me, spoke strongly American-accented French. (I never, ever try to imitate her voice—an odd blend of shrillness and warmth—or her chortling laugh. That I leave to Meryl Streep.)

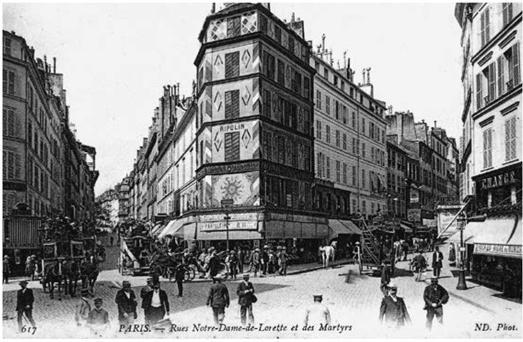

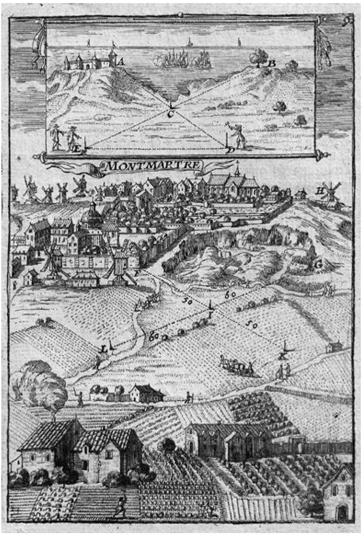

The rue des Martyrs does not belong to monumental Paris. You won’t find it in most Paris guidebooks. About a mile north

east of the place de l’Opéra and half a mile south of the Sacré-Coeur Basilica, it cuts through former working-class neighbor-hoods of the Ninth and Eighteenth Arrondissements. It lacks the grandeur of the Champs-Élysées and the elegance of Saint-Germain. Yet it has made history. On this street, the patron saint of France was beheaded, the Jesuits took their first vows, and the ritual of communicating with the dead was codified. It was here that Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir painted circus acrobats, Émile Zola situated a lesbian dinner club in his novel

Nana,

and François Truffaut filmed scenes from

The 400 Blows

. The rue des Martyrs is mentioned in Gustave Flaubert’s

Sentimental Education

, arguably the most influential French novel of the nineteenth century, and in Guy de Maupassant’s

Bel-Ami

, a scandalous tale of opportunism and corruption. More recently, Pharrell Williams, Kanye West, and the band Phoenix came here to record songs at a state-of-the-art music studio.

The rue des Martyrs is not long—about half a mile, no longer than the stretch of New York’s Fifth Avenue between Rockefeller Center and Central Park. But its activity is much more concentrated: nearly two hundred small shops and restaurants are packed into its storefronts. Although it is wide enough for cars to park on one side, it is so narrow that people living in apartments facing the street know the comings and goings of residents and shopkeepers just across the way. There is the old woman who stands on her balcony for a cigarette each morning, the man who washes his windows every Tuesday, and the young couple who open their shutters and play loud music before going to work.

Early each morning, a respectable-looking young woman heads to her job at a massage parlor that everyone knows offers

more than massages, while nannies from far-off places like Mali and Cameroon drop off children at a day-care center hidden inside a courtyard. Late each afternoon, as residents begin returning home from work, an elderly woman sings to herself, filling the sidewalks with childish tones of “la, la, la, la,” while a battered musician with missing teeth and a guitar strapped on his back wanders in and out of shops, displaying varying degrees of coherence.

Every Saturday morning, I sit at the café at No. 8 and face the rue des Martyrs to watch the show. The actors perform on six mini-stages on the other side of the street: my greengrocer and my favorite cheese shop and my butcher at No. 3, my fallback cheese shop and my fish store at No. 5, and the front of my supermarket, where an itinerant chair caner sets up at No. 9. I order a

café crème

. Mohamed (a.k.a. Momo) Allili, the day manager, doesn’t mind when I bring a sugared brioche from my favorite bakery next door. This café serves as my personal salon, where neighbors and merchants come and tell stories of the street’s history and its transformation over the years.

The rue des Martyrs has managed to retain the feel of a small village despite the globalization and gentrification rolling over Paris like a bulldozer without brakes. As an outsider, I am part of the forces of modernization that threaten to dismantle the street’s centuries-old community. Yet over time—partly through what I call random acts of meddling, inspired by my journalist’s curiosity—I have broken into this tight-knit community. I have built relationships with those who live and work here—not necessarily deep friendships, but attachments created by a shared passion for a discrete geographical space. At first they involved transactions—goods bought and sold—and with enough time, they extended to experiences shared.

It is the tenacity of the small, traditional merchants and artisans that keeps the character of the street intact. Now they know me, and I know them. I’ve spent so much time on the street that I’ve learned the landscapes of their lives: their aches and pains, their vacation destinations, the names and ages of their children. I’ve heard about the family wedding back home in Tunisia and the attempted holdup of the jewelry store by gunmen. I know who takes a long, hot shower every morning and who has a fantasy of meeting the actress Sharon Stone. I know who suffers from diabetes and who secretly dyes his hair.

I know about the merchant whose marriage ended in divorce when he discovered his wife in bed with another man. He went for the lover’s throat, spent forty-eight hours in jail, and was given a fine and a one-month suspended sentence for assault.

“What would you do if you found your husband in bed—in your bed—with another woman?” he asked me over coffee. “Wouldn’t you react with rage?”

I told him I might kneecap him, Sicilian-style.

I know about the torture Kamel the greengrocer endured when he went home to Tunisia for a sciatica cure. The local healer made deep cuts in Kamel’s ankle and back until he touched the sciatic nerve. Then he took a nail with a head the size of a quarter, heated it in charcoal until the head turned red, and seared the cuts. He didn’t use anesthesia. The large burns on Kamel’s skin healed unevenly. I know this because he lifted his shirt and one of his trouser legs to show me. Somehow, the unconventional treatment worked.

The street is a hothouse of intimacy. Information becomes currency that has value and can be passed around. When I told

Annick, who runs the cheese store at No. 3 with her husband, Yves, that a new merchant had been rude, she told my friend Amélie, who immediately reported the story back to me with 20 percent more color and drama. When I reminded Ezzidine, then the greengrocer at No. 16, that he had promised to take me to the Rungis wholesale food market just outside of Paris, he informed me that he knew I had also asked one of his competitors down the street to do the same. He wasn’t angry; he just wanted me to know that he knew.

The feelings of community are strongest among merchants clustered at the bottom of the street, who refer to themselves as “family.” Service trumps competition. When the greengrocer at No. 3 ran out of flat green beans, he grabbed some for me from the greengrocer at No. 4, across the street. My pharmacy has female pharmacists who know my daughters and me so well that I often consult them before calling the doctor.

When I needed a seat small enough to fit into a shower after my older daughter, Alessandra, sprained her ankle, I went first to the hardware store at No. 1, then to the variety store at No. 16. Finally, Ezzidine walked me over to Orphée, the sliver of a store selling jewelry and watches at No. 9, across the street, and introduced me to Joseph, the owner. Joseph gave me a chair and told me to bring it back when I no longer needed it.