The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs (7 page)

Read The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs Online

Authors: Elaine Sciolino

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #History, #Biography, #Adventure

She invited me to sit in a large dining room with open windows facing the garden. Then, finally, she told me her name: Liliane Kempf. She was a Spanish-language teacher married to Bertrand, a computer specialist; both were retired. She served me a large slice of homemade blueberry tart and a glass of orange juice; she seemed too eager to talk to spend time making coffee.

She told stories about the rue des Martyrs in the old days, when itinerant merchants sold fruits and vegetables from hand carts they pulled up the street and a dairy shop ladled fresh milk out of huge metal cans. She said her late aunt remembered horse-drawn carriages ferrying pedestrians uphill during winter, when it was too slippery to walk. My favorite story was the one she told about an unknown waif of a street singer, Édith Giovanna Gassion. Poor, thin, and only four feet, eight inches tall, she sneaked in and out of courtyards in the neighborhood, including those

along the rue des Martyrs, to sing to the residents. Seduced by her voice—and her gumption—they threw coins to her from their windows, first wrapping the coins in paper so they would not roll away. I already knew the story’s end. Eventually she made it big—as Édith Piaf.

. . .

An American writer who had come to visit France . . . asked quite naturally what it was that had kept me here so long. . . It was useless to answer him in words. I suggested instead that we take a stroll through the streets.

—H

ENRY

M

ILLER ON

LIVING IN PARIS

T

HE RUE DES MARTYRS BECAME AN ADDICTION. I GOT

hooked on its spirit: the rhythm, the collective pleasures, the bonding with merchants, the way I felt when I walked up and down it. I became like Louis-Sébastien Mercier, the eighteenth-century writer and first street reporter of Paris. He wandered on foot, recording the everyday habits and customs of people of all classes and professions: prostitutes and policemen, servants and street vendors, criminals and priests. And artists, beggars, philosophers, greengrocers, and washerwomen. Mercier was driven by curiosity, not destination. He turned his impressions into

Tableau de Paris,

a twelve-volume, twenty-eight-hundred-page collection of sketches of Paris life on the eve of the 1789 Revolution. Alas, Mercier got the revolutionary spirit all wrong—he predicted that Parisians were too self-satisfied to embrace a serious uprising.

“The Parisian’s instinct seems to have taught him that the little more liberty he might obtain is not worth fighting for,” he wrote. “Any such struggle would imply long effort and stern thinking. He has a short memory for trouble, chalks up no score of his miseries, and has confidence enough in his own strength not to dread too absolute a despotism.”

Tableau de Paris

was quickly overtaken by events. Today it is a forgotten jewel of French literature.

I have a complicated relationship with Mercier, as he was the subject of a doctoral dissertation I long ago started and failed to finish. But I have faithfully admired him as a pioneer of walking, wandering, and watching. “I have run around so much while drawing my

Tableau de Paris

that I may be said to have drawn it with my legs,” he wrote.

Mercier was more than a detached observer. He flouted social conventions and opened conversations with all sorts of people. “I have made myself acquainted with every class of citizen. . . . Many of the inhabitants of Paris are strangers to their own town. Perhaps this book may teach them something or at least may put before them a clearer and more precise point of view.” Immediacy, not deep analysis, was his objective: “My

Tableau

is fresh from my pen, as my eyes and my ears have been able to piece it together.”

More than half a century later, the poet Baudelaire—who spent considerable time on the rue des Martyrs—gave new defi

nition to the passionate wanderer-spectator, who by then had become a familiar Parisian type. He called him (it was always a man) a

flâneur.

“The crowd is his habitat, as air is for the bird or water for the fish,” he wrote. “His passion and his profession is to wed the crowd. . . . To be away from home, but to feel oneself everywhere at home.” As a female

flâneuse

, I had to recalibrate the way I gathered information. I had to wander up and down the street at random hours of the day and night. I had to hang around people and drop in and out of their shops and their lives with regularity. I had to spend long stretches doing nothing. I had to stop looking at my watch. I had to “wed the crowd.”

ASIDE FROM THE THEATER,

journalism is one of the few professions in which you can play-act. Over the years, I have walked through cornfields in Kansas dressed like a farmer to hear about the worst drought in memory. I’ve cast myself as a war correspondent in flak jacket and helmet, taking cover from an Iranian air attack in the southern marshes of Iraq. I’ve played diplomatic analyst wearing a well-cut suit, Chanel pumps, and knitted brow to interview the French president about world peace.

When I lived near the rue du Bac, in the Seventh Arrondissement, I assumed the role of a person of standing: Paris bureau chief for the

New York Times,

married to an American lawyer at one of the most respected French law firms. The streets in the Seventh ooze elitism, not

égalité

. Pedigree, impeccable manners, and—in a perfect world—a country house and hidden wealth add to one’s cachet. People didn’t think to ask about my Sicilian roots.

On the rue des Martyrs, there is no need to play-act. My family history gives me status. I tell people

“Je suis issue de

l’immigration”

—“I have an immigrant background”—and a classic American success story. My grandparents left Sicily for the United States and worked hard to escape poverty. My most treasured family photo shows my grandfather as a young boy in Caltanissetta posing with his white-bearded grandfather, who holds a staff by his side. The photo is about 130 years old. This is the identity I bring to the rue des Martyrs.

I learned the street’s early morning rhythm by jogging from bottom to top. The first sound is a six a.m. rush of water, as street sweepers dressed in chartreuse and emerald-green uniforms open valves to send the flow downhill along the gutters. It is part of the Paris cleaning ritual but also a waste of water and a contributing factor to the wet underbelly of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette Church, at the bottom of the street. Depending on the day, I might have to dodge an all-night crowd gathered at Bistrot 82 for more booze and an early breakfast.

By six-thirty, the first food merchants have arrived. The metal shutters of the shops open with a crashing and screeching that ricochets off the old concrete and stone walls. By seven, the roar of trucks delivering food takes over. Every fifteen minutes or so, the 67 bus climbs the street, announcing its presence with a bell. Dogs are late sleepers in my neighborhood, seldom out before eight or eight-thirty. Their masters seem to be a civic-minded bunch who rarely leave behind dog excrement—unlike residents on my old street in a much fancier part of Paris.

The three bells of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette ring at nine a.m., as they will every hour until eight p.m., plus three times a day for the Angelus prayer. Boutiques begin to open at ten a.m. When school lets out, in late afternoon, children crowd the sidewalks with their parents (mostly mothers) or nannies.

A few hours later, the shops shut down just as the cafés and bars fill up. By nine p.m., the restaurants are jammed. The transvestite Cabaret Michou show ends at one a.m.; Bistrot 82 closes an hour or so later—only to open again at five on some mornings. The café-bar-bistro La Fourmi stays open until four a.m. on weekends.

On Sunday mornings, the rue des Martyrs closes to traffic. Sunday Mass is not the main event, since this has been a street of the political left, where church attendance occurs mostly on religious holidays like Christmas and Easter. Instead, people walk up and down, greeting each other with double-cheeked air kisses. Most want to buy the ingredients for Sunday lunch; some want to see and be seen.

But it’s not a Paris version of “The Saturday Route,” Tom Wolfe’s essay about Madison Avenue on Saturday afternoons in the 1960s, when famous people strode briskly and exchanged wet smacks on the cheek. The rue des Martyrs is not as frenzied. People tend to

flâner

, to stroll, dipping in and out of food shops and standing in line patiently when they must. The lines are tolerated, even welcome, since they afford patrons an excuse to chat.

The Sunday morning ritual is familiar to anyone who knows the street. The butcher on the east side sets up a separate counter offering rotisserie chicken and roasted potatoes to satisfy a line of customers who want ready-made food for lunch.

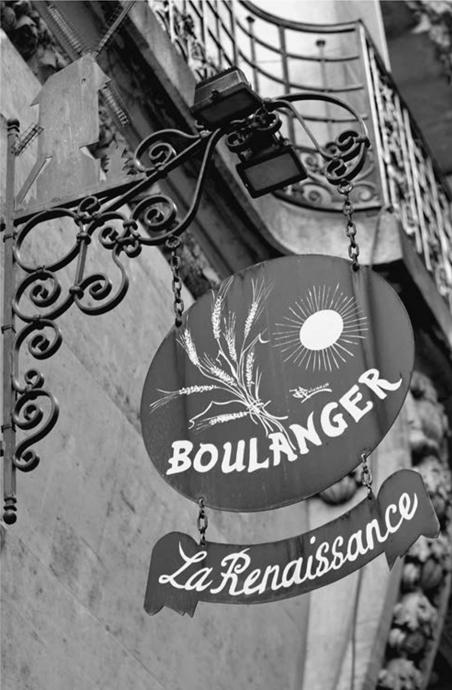

The Levins, who run the bakery a few doors away, add an extra table for baguettes and brioches only, which speeds transactions. Every Sunday, Philippe Levin bakes a brioche loaf with a double dose of butter and a top layer of caramelized sugar. There is a more famous baker up the street, Arnaud Delmontel, who won awards from the Professional Chamber of Artisanal

Bakers and Pastry Chefs for best traditional baguette in 2007 and for best

millefeuille

pastry in 2010. But if an award were given to the best sugar-topped brioche, Philippe would win, hands down.

On the street itself, everyone has a place. Political activists lay claim to the base in front of the barricades that close it off to traffic—a prime spot, since four other streets feed into the rue des Martyrs. On any given Sunday, three or more political parties might compete for the crowd’s attention.

The French Communist Party (PCF)—with its Ninth Arrondissement chapter a few blocks away—is particularly active. One Sunday in early 2014, its members distributed a petition condemning an initiative to allow stores to open on Sundays. It accused the “financial powers” of seeking to control the free time of the working class, of damaging small shopkeepers unable to compete with large chains, and of destroying the fabric of society. It asked for new members, using the following pledge: “To make the human choice, to combat the right, to continue the Left Front, I am joining the Communist Party.”

LIFE ON THE RUE DES MARTYRS

is governed by more than the time of the day and the day of the week. As I wander the street with my notebook, Louis-Sébastien Mercier–style, I am also both bombarded and embraced by the shock of the new.

A designer olive oil shop replaced a greengrocer in 2008; a designer jam shop replaced a clothing store in 2011. A traditional charcuterie had been at No. 6 since 1849; when it moved out, in 2011, a designer rotisserie moved in.

In what seemed like record time, an all-purpose family-run convenience store that stayed open until midnight was replaced

by a Subway sandwich shop, then by an Italian food boutique, and finally by a shop offering honey and other bee-related products. Five chocolate shops compete within three blocks.

Farther up the street, a shop selling minimalist modern tableware replaced Et Puis C’est Tout, which specialized in mid-century decorative objects. This was where I used to find vintage Ricard water carafes and 1960s lighted glass geographic world globes cast off by French high schools when the Soviet Union broke up and suddenly there were fifteen republics to paint in. Where once there were stores selling a surprising variety of useful objects, like fabrics and thread, now there are boutiques selling one frivolity at a time:

choux

pastries, madeleines, cookies, Spanish

pata negra

cured ham, and ice creams in New Age flavors like chocolate with

espelette

pepper. In 2014 the London

Sunday Times Magazine

named the rue des Martyrs one of the best shopping streets in the world, signaling its discovery well beyond the neighborhood. The southern part of Pigalle, to its west, has been nicknamed SoPi (pronounced “soapy”).

Lamenting change is nothing new. “The sense of neighborhood has gone, never to return,” the American art critic John Russell wailed in his classic 1975 study of Paris. “The one-person shop, the solitary craftsman, the frugal, secret, and yet dignified life—all have been lost.” Eight years later, in an essay called “My Paris,” the novelist Saul Bellow sounded a similar death knell: “A certain decrepit loveliness is giving way to unattractive, overpriced, overdecorated newness.”