The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (10 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

As it turns out, there

are

numerous records of such a language, and it was spoken in just those places unambiguously identified in classical literature as Celtic or occupied by Celts from at least as early as 300

BC

: France south of the Seine, northern Italy and Spain (

Figures 2.1a

and

2.1b

). To classical authors, the two more northerly regions were known respectively as Trans-Alpine Gaul and Cis-Alpine Gaul, named from the Roman point of view: Gaul-on-the-far-side and Gaul-on-the-Roman-side of the

French

Alps.

Figure 2.1a

Who were the Celts in classical times? According to Caesar, Gaul was divided into three parts. The middle part, spoke celtic and was mainly south of the Seine and Marne, although there was a north-eastern extension as far as the Rhine. In the north, the Belgae were mostly ‘descended’ from Germani. Arrows show Celtic tribal invasions of Italy (around 600

BC,

according to Livy).

These dead but not completely lost languages, for which there is clear archaeological evidence, are ancient Gaulish in Trans-Alpine and Cis-Alpine Gaul, and Celtiberian in east-central Spain. The evidence for Gaulish is extensive and includes bilingual inscriptions of Rosetta Stone quality and inscriptions accompanied by unmistakable depictions.

2

Gaulish inscriptions are found in southern France from the third century

BC

until the first century

AD,

initially in Greek script and later, post-Caesar, in Roman script. Some Roman inscriptions are found in central France; the latest of them, from the third century

AD

, was recently discovered (1997) in Châteaubleau, about 40 km south-east of Paris.

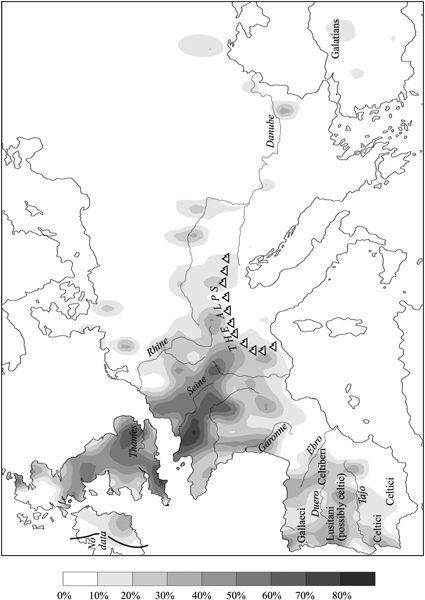

Figure 2.1b

Where was the evidence for celtic language in classical times? Map of Europe and Asia Minor with the percentages of ancient place-names that were celtic shown as contours. The highest frequencies were in Celtica, Britannia and Iberia. Their absence in western Ireland is due to lack of data. Unexpectedly low rates, e.g. in northern Italy and Galatia, are due to the 10% contour cut-off point used for contrast.

Although very similar, the Italian or Cis-Alpine version of Gaulish is usually called Lepontic. Lepontic is not an Italic language, although the earliest inscriptions from northern Italy are dated (controversially) to the sixth century

BC

and are written in Etruscan script. This early celtic-linguistic date in Italy would clearly be consistent with Livy’s disputed historical claim for early Celtic invasions of northern Italy.

3

Gaulish, lacking its own script, would be unlikely to reveal similarly early dates for inscriptions in France before the Roman invasion.

For some reason, however, Collis seems particularly unwilling to accept Livy’s early date of 600

BC

for an initial Celtic invasion of northern Italy from Gaul. However, if we review Polybius and Livy for the actual origins of the first northern Italian Celts,

4

in spite of their disagreement over the exact date (respectively c.400

BC

and c.600

BC

), we find no suggestion that they came across the Alps from any direction other than the west – from Gaul, south of the Seine. Livy in fact gives the names of several Alpine passes, which makes it clear that these early invading Gauls came from Trans-Alpine Gaul (i.e. southern France) rather than from Germany or Austria.

5

This early date – written in stone – is consistent with trends to move back the age of the celtic-language family using other methods (which I shall discuss further at the end of this

chapter and later in the book). Also, the early break-up of celtic languages, combined with Caesar’s language link, is consistent with the inference from Himilco’s

Periplus

that insular Celts could have arrived in the British Isles at least as long ago as the mid-first millennium

BC

(see

Chapter 1

).

The quality of these extant records of an ancient Gaulish relative of the insular-celtic languages, and its clear association, in time and place, with the Celtic cultures of south-west Europe, make Pezron’s and Lhuyd’s suggestion of a Celtic link across the Channel less of a false leap of imagination than Simon James and John Collis imply. The critical false step seems to have been the conviction of nineteenth- and twentieth-century archaeologists that the Celtic homeland was in Central Europe. Far from being the nationalist, New Age amateurs that the Celto-sceptics paint them as, those Enlightenment bookworms Pezron and Lhuyd made the most useful theoretical advance in the past three hundred years of Celtic studies.

The Gaulish records are not the only evidence of celtic languages in south-west Europe, but they are the best, both for textual reference and for inscriptions.

6

Iberia is the other region with the clearest evidence for the coincidence of both Celtic people and celtic languages in early classical times.

7

Collis reviews a number of classical sources which refer to Celts in Iberia. These mention mainly Celtiberians, who appear in the texts as a hybrid product of invading Gauls from France and indigenous Iberians, who battled at first, then buried the hatchet and joined cultures. Other Celtic groups are referred to as being in Iberia, such as the Celtici.

8

The record of Iberian inscriptions shows Celtiberian as a major Continental branch of celtic languages. This evidence

comes from around seventy inscriptions totalling around a thousand words dating from the third to the first century

BC

. These were mostly written in the Iberian script but sometimes also in Roman script. The outstanding ones are three major texts on bronze tablets found at Bottorita, near Zaragoza in north-central Spain. The longest and most famous inscription is a

tessera hospitale

(a written promise of hospitality), written in Celtiberian on both sides. From the existence of four rock inscriptions in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula, Lusitanian has also been suggested as an ancient celtic language. But this attribution has nothing like the quality of written evidence that Celtiberian has (

Figure 2.1b

).

9

The archaeological evidence does indicate a specific Celtiberian cultural area coincident in time and place with the inscriptions in north-east central Spain to the west of the River Ebro. There is also extensive and overlapping textual, place-name and personal-name evidence for a Celtic presence throughout the north-westernmost two-thirds of the Iberian Peninsula (

Figure 2.1b

).

10

Tribes known as the Celtici on the western Atlantic coast of the peninsula seem well attested,

11

which is consistent with evidence from place-names.

The use of evidence derived from place-names to suggest a celtic-linguistic origin has been criticized. In some cases, the arguments for derivation from celtic appear circular, self-fulfilling and even deliberately misleading. More recently, stricter linguistic criteria have been applied in order to reduce dubious attributions, particularly to celtic.

12

From the distribution of names with the ending -

briga

(‘-hill’), one celtic element that does seem to have consistency and common specificity with place-name evidence elsewhere,

13

it appears that the Celtici and

other putative Celtic tribes, such as the Gallaeci and Lusitani, spread up the rivers from the coast, deep into the hinterland of northern and western Spain (

Figure 2.1b

).

That apart, the place-name evidence for celtic languages much east of the Rhine or in other parts of Northern Europe is not convincing. A recent workshop was convened by linguists to establish just what proportion of European place-names on Ptolemy’s famous map of the second century

AD

could be reliably identified as celtic.

14

Several broad conclusions emerged. Numerically, the centre of gravity and greatest diversity of forms for Continental celtic place-names were in France south of the Seine, Spain and northern Italy, as predicted by the distribution of early celtic inscriptions. There were very few celtic place-names much east of the Rhine or north of the Danube. There is a similar paucity of celtic place-names in the southern Balkans, Romania and Hungary, to the south-east.

15

Archaeologist Colin Renfrew comments on the circularity of linguistic arguments based on ‘evidence’ for Celtic populations in Eastern Europe: ‘Very often the claims for a Celtic population in those areas are backed up by discussion of objects found there which are in the La Tène art style.’

16

Clearly, the La Tène art style is not linguistic evidence of Celticity, and its Celtic connection is based only on the Central European Celtic homeland theory, thus creating a circular loop of association. There is also a possibility that the Celtic invasions into Greece and beyond into Anatolia (in modern Turkey) took celtic languages into the region subsequently known as Galatia. This is borne out by the new systematic place-name work (

Figure 2.1b

).

17

But, as Renfrew points out:

Whatever the status of Galatian Celts, they have little significance for the origin of the Celtic languages, since it has never been suggested that a Celtic language was spoken in Anatolia prior to the supposed arrival of these intruders in the late third century

BC

.

18

To summarize: in agreement with inscriptional evidence for early celtic-language distribution, classical historians seem to place the oldest records of the Celts in Narbonne, southern France, and also Italy and Spain, the earliest dates being written in stone around 600

BC

. The simplest interpretation, and the one most consistent with the partially conflicting sources, is that the Celts originated somewhere near the south of France and then spread southwards to Spain and eastwards across the French Alps to invade parts of Central Europe, Italy and even Anatolia by at least the third century

BC

. The classical writers’ confusing practice of conflating Gauls and Celts was common but acknowledged specifically, even by Caesar. We have to assume that he did intend the reader to understand that there were celtic speakers as far north as the Seine – as evidenced by people who called themselves celtic speakers. Their presence in the areas identified by Caesar is again supported by the distribution of place-names ending in -

briga

. However, it is not clear

when

they got there. The classical view of Celts as people speaking celtic languages and originating in south-west Europe is supported by writers such as Strabo, Diodorus Siculus and Caesar. The modern view, derived from Buchanan, Pezron and Lhuyd, that these classical celtic languages are related to modern insular-celtic languages, is well supported by the finding of extant celtic inscriptions and other primary linguistic evidence

confined to those areas where Celts were first attested – namely southern France, Italy and Spain.

On the other hand, it is difficult to infer a clearly Central European origin for Celts from any of the classical writers. To cite the La Tène or Hallstatt art styles as favouring such an origin is an invalid argument, based on nineteenth-century misconceptions. And for twentieth-century scholars to cite those styles as primary evidence for Celts immediately becomes a circular and invalid argument. Further, there is no linguistic evidence whatsoever that those celtic speakers originated in southern Germany or anywhere east of the Rhine. Use of the excuse ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’ is no good either because the original assumption that Celts were associated with the very real spread of La Tène and Hallstatt art styles had inadequate textual or linguistic support in the first place.