The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (8 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

However, if Cunliffe is correct, then Pytheas, with such satisfactory travel arrangements, is unlikely to have been travelling alone, without a courier, or as a novice tourist. In other words, he would have been taking advantage of a pre-existing river– land–river–sea trade route worked out by the established local inhabitants of Keltiké. According to the Central European home land theory, these locals could not have been Celts when Pytheas made his trip in the fourth century

BC

since, as Cunliffe goes on to show,

37

the Celts would have been either still in their Central European homeland or moving east into northern Italy. Yet Himilco, who made his own trip up the Atlantic coast nearly two centuries before, seemed to claim that the power of the Celts was very much in evidence in northern Britain.

Again we are led down the Atlantic coast rather than into Central Europe for the Continental connections of the Celts. Strabo himself is explicit on the antiquity of the Celts in the

region of Narbonne, where Pytheas might have started his journey across Keltiké:

This, then, is what I have to say about the people who inhabit the dominion of Narbonitis, whom the men of former times named ‘Celtae’; and it was from the Celtae, I think, that the Galatae as a whole were by the Greeks called ‘Celti’ – on account of the fame of the Celtae, or it may also be that the Massiliotes, as well as other Greek neighbours, contributed to this result, on account of their proximity.

38

In this passage Strabo defines the geographical and tribal origin of the term ‘Celt’ and how it then spread by some process of inclusive labelling. If there should be any doubt about this southern centre of gravity, there are other classical commentators who concur. Diodorus Siculus, writing in Greek rather earlier than Strabo, states:

And now it will be useful to draw a distinction which is unknown to many: the people who dwell in the interior above Massalia [Marseilles], those on the slopes of the Alps and those on this [northern] side of the Pyrenees mountains are called Celts (Keltoi), whereas the peoples who are established above this land of Celtica in the parts which stretch to the north, both along the ocean and along the Hercynian Mountain [today’s Massif Central], and all the peoples who come after these, as far as Scythia, are known as Gauls (Galatai); the Romans, however, include all these nations together under a single name, calling them one and all Gauls (Galatai).

39

This apparently independent confirmation of Strabo’s geographical identification of a Celtic heartland in the extreme south of France is very revealing. First, it seems to limit their range ‘of

former times’ not to southern Germany, but to Narbonne: a small area around Marseilles, north of the Pyrenees, west of the Alps and south of the Massif Central, and probably east of Aquitane. Second, but equally important for untangling the Celtic mystery, both Greek authors feel the need to explain how the local term ‘Celt’ came to be conflated by Roman writers such as Julius Caesar with the much larger regional labels of ‘Gaul’ and ‘Gauls’.

Apart from anything else, this southern homeland would go a long way to explaining anachronistic mentions of Celtici in the south-west of Spain and Celtiberi to the east of Madrid as early as the sixth century

BC

.

40

This information comes from authors such as Herodotus, Eratosthenes (third century

BC

)

41

and Ephorus (405–330

BC

), who is cited by Strabo: ‘Ephorus, in his account, makes Celtica so excessive in its size that he assigns to the regions of Celtic most of the regions, as far as Gades [Cadiz], of what we now call Iberia’ (see also below).

42

Diodorus Siculus, probably citing Poseidonius, states that the ‘Celtiberes are a fusion of two peoples and the combination of Celts and Iberes only took place after long and bloody wars’.

43

The Romantic mythologist Parthenius of Apamea (first century

BC

) gave a telling and charming version of the popular legend of the origins of the Celts in his

Erotica pathemata

,

44

which preserves the Spanish connection and even hints at Ireland. Heracles was wandering through Celtic territory on his return from a labour – obtaining cattle from Geryon of Erytheia (probably Cadiz). He came before a king named Bretannos. The king had a daughter, Keltine, who hid Heracles’ cattle. She insisted

on sex in return for the cattle. Heracles, struck by her beauty, had a double motivation to comply. The issue of this union was a boy and a girl. The boy, Keltos, was ancestor of the Celts; the girl was Iberos. Rankin speculates further that the homophony between ‘Iberos/Iberia’ and the Irish mythical ancestor, Eber, may be more than coincidence.

We can provisionally accept this literary evidence of a Celtic homeland in the south of France, but several critical questions remain. How much of the spread of ‘the Celts’ was due to this conflation of terms (combined with ‘the fame of the Celts’ and consequent Roman labelling, as Strabo speculates), and how much was due to real population migration, invasion and/or cultural expansion? This issue might be amenable to genetic study, as I show later, but it forces a reappraisal of the terrifying and documented Celtic invasions of Southern and Eastern Europe (including Italy and Anatolia) in the fourth and third centuries

BC

, in which they sacked Rome itself (390

BC

).

45

Instead of streaming across the high passes of the Alps from Germany and Austria to the north,

46

could these Celts have been anticipating Hannibal’s example, a couple of centuries later, by crossing the Alps farther south into Italy, from a homeland in the south of France?

Rankin, in his book

Celts and the Classical World

, has a whole chapter on the early and long association of the Celts with the south of France and the Greek colony of Marseilles. On the persisting assumption that the Celts came from Central Europe, he has this to say:

It is reasonable to suppose that the Celts had arrived in the region of Southern France some considerable time before their irruption into Northern Italy. By the fifth century

BC

they had

established themselves firmly in what was to become Cisalpine Gaul, and at the end of that century were strong enough to threaten the safety of Rome.

47

In spite of placing Celts so early in southern France, Rankin is still clearly convinced of the primacy of southern Germany as the Celtic homeland. He describes as ‘an abiding preoccupation of the Roman mind … the vulnerability … to invasion … especially from the north.’

48

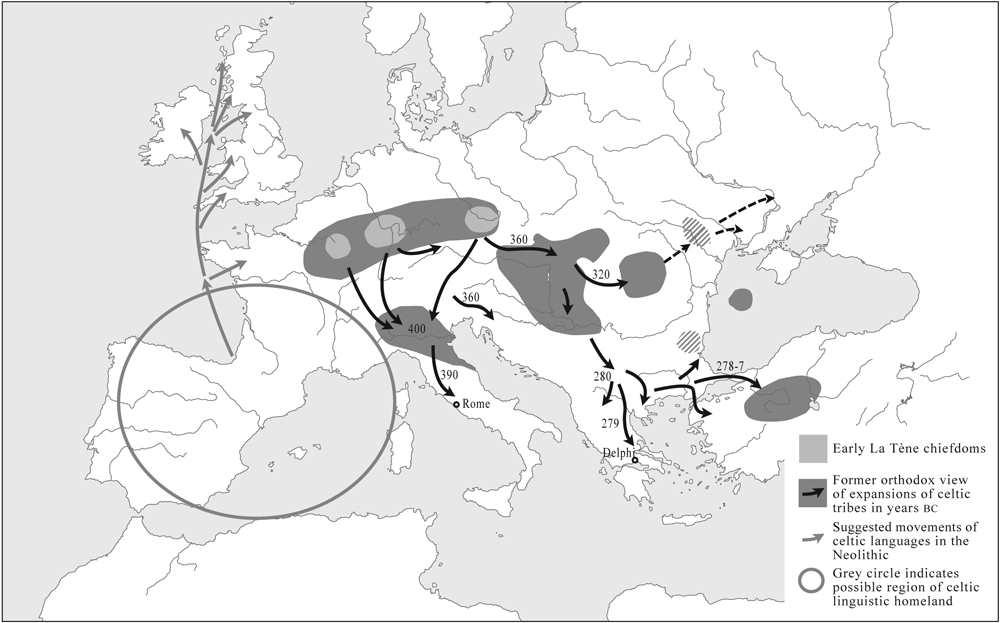

Cunliffe, in his 1987 book, is more explicit, drawing maps (

Figure 1.3

) showing big Celtic arrows driving south from the Marne–Moselle–Bohemian region straight into Italy.

49

Yet the Celtic tribes that Livy and other Roman historians describe as taking part in these fearsome fourth-century

BC

invasions, the Senones and Boii, were associated, in Caesar’s time, with parts of France south of the Seine.

50

It may be claimed that several of these Celtic tribes, for instance the Boii, were subsequently associated with Bohemia. But Strabo makes it clear that Bohemia was where the Romans, who had subsequently got the upper hand over the Celts occupying northern Italy, pushed them later at pain of extinction.

51

While archaeologists base the identity of the northern invaders on types of artefact, there is very little support in the classical literature for a Celtic homeland in the north, let alone for the Celtic invasion of Italy coming directly from the north through the high passes of the Austrian and Swiss Alps.

52

Figure 1.3

Which Celtic homeland? Iron Age in Central Europe, as argued from the Hallstatt and La Tène expansions, or a Neolithic trail from south-west Europe, as suggested by language and Atlantic cultural distributions?

As for the third-century

BC

Celtic invasions of the Italian Adriatic coast and Greece and Asia Minor, Strabo is again explicit in placing their ultimate starting points in France south of the Seine. The Veneti came from Armorica,

53

and the Volcae Tectosages, who invaded Delphi in Greece and Galatia in Turkey, came ultimately from the Pyrenees.

54

Strabo cites Julius Caesar extensively in his description of the distribution of the Celts in Gaul. So, bearing in mind Strabo’s clarification on the ultimate southern origin of the term ‘Celts’ in Narbonne and its extension to Gauls, we might as well hear now what the iconic warrior-historian had to say himself in his memorable but lean opening lines of the

Gallic Wars

:

All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, those who in their own language are called Celts, in our [Latin] Gauls, the third. All these differ from each other in language, customs and laws. The river Garonne separates the Gauls from the Aquitani; the Marne and the Seine separate them from the Belgae.

55

Although debunkers of the Celtic myth have argued that, in writing this document, Caesar had hidden agenda aimed at self-justification to his Roman audience, the lack of contradiction by other authors gives authenticity to this simple description (

Figure 2.1a

).

First, Caesar places a northern limit on the Celts within Greater Gaul and in Western Europe as a whole. The Seine and the Marne define this northern limit, which is much farther south than today’s French border and excludes all but a small sliver of

the putative Central European Celtic homeland. Significantly, Caesar includes southern French locations of the tribes Livy identified as previously having invaded Rome.

56

Caesar’s use of these two rivers, as both northern Celtic and celtic-language boundaries, is consistent with evidence from place-name analysis. (I shall come back to this northern Celtic boundary from another perspective in

Chapter 7

, and at the same time discuss the controversial place-name evidence in terms of where celtic languages gave way to Germanic-branch languages in Caesar’s Gaul.)

Second, consistent with Strabo’s narrower south-eastern French Celtic homeland, Caesar’s Celtic zone of Gaul included, by default, Narbonne in the south. Third, and perhaps most important in the context of identity, Caesar, in his economic style, tells us that the term ‘Celt’ is applied to one region only, and also identifies people of this region of Greater Gaul as ‘Celtic in their own language, Gallic in ours’ (‘

qui ipsorum lingua Celtae, nostra Galli appellantur

’). Caesar may have conflated Celts and Gauls elsewhere, but his meaning on this point is unambiguous, even to my rusty Latin: the Gauls of this central region of Greater Gaul called themselves Celts in their own language. I shall come back to the relevance of celtic languages, but first a digression on the Celtic homeland.

By this time in my reading of Rankin, I had seen sufficient of his key quotes from classical sources to get a strong impression of Celtic origins in south-west Europe, rather than the Central

European homeland he was promoting in the 1980s. I almost began to wonder why Simon James had directed me to read such books if the evidence used, and the classical texts referred to, were so contradictory to the orthodoxy of the Celtic Central European Iron Age homeland.

At this point I belatedly received the new book written by the Celto-sceptic John Collis:

The Celts: Origins, Myths, Inventions

.

57

Collis, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Sheffield and a leading British authority on the European Iron Age, confesses, on the first page of his acknowledgements, to having been a sceptic since his Cambridge student days in the 1960s, and perhaps even from his schooldays, when he first read Caesar and Herodotus. It is a testament to the power of academic conservatism that he has waited so long before committing himself so publicly in book form. Could this be regarded as an act of academic bravery, even in someone so senior? In Hans Christian Andersen’s tale ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, only a small boy had the temerity to point out that the Emperor had not a stitch on.